By Eva Hernandez

The air is rife with the sounds of men preparing for battle on the front lines. This is the real deal, and Private Joe Vargas is ready. He lumbers off the back of the Army truck – just barely – and moves forward.

Two bandoliers of M1 clips are strapped to his chest and he is armed with as many grenades as he can carry. The first lieutenant meets him with a critical eye.

“He looked me up and down,” Vargas said. “I saluted him, he saluted back and then he went around me, didn’t say a word. Then he got in front of me and said, ‘Vargas, who in the hell do you think you are, Pancho Villa?’”

He’d weighed himself down with so much ammunition he could hardly move. For 18-year-old Vargas, the trade-off was worth it: the possibility of death was ever-present, and being prepared was of paramount importance.

“Of course I knew better, you know,” Vargas said. “If you’ve been trained to fight, you’ve got to be able to move around. But I said, ‘Well, I’m not going to go get killed on account of ammunition.’”

*********

Vargas’ early life is marked by a series of moves between Austin, which is his city of birth, and Ft. Worth, the city he still calls home. His father worked as a greens keeper at a local golf course, while his mother stayed home with her six children.

Despite his father’s long working hours, the family struggled to make ends meet. New clothes and shoes were a luxury seldom afforded.

Vargas recalls that when he started school, he only knew one language: Spanish.

“I was held back in the first grade twice because I had no idea what was going on,” said Vargas, adding that he decided as a boy that he would have his children speak primarily English at home.

“I didn’t want them to go through that in school,” he said.

As a 10-year-old, Vargas was already working at the same golf course as his father. The war, however, would eventually change the boy’s situation.

“I was working when I got drafted,” Vargas said. “On March the 18th [1944], I registered. By June the 30th, I was gone.”

*********

Vargas underwent basic training for anti-aircraft artillery at Fort Bliss in Texas. By September of that same year, he was transferred to the 28th Infantry Battalion, 8th Infantry Division and trained at Camp Massey in Paris, Texas.

“The Germans were taking their toll on us and they were running out of infantrymen,” Vargas said. “So we went into the infantry. We got shipped from there [Paris] to Maryland and from there to New Jersey and from there to the New York Harbor to board the ship to go overseas.”

A British troop ship carried Vargas across the Atlantic in January of 1945. His first time out on the ocean would prove to be rough.

Private Vargas spent his second night at sea poised to abandon ship with the rest of his company, listening to the thunder of attacks on suspected German U-boats. Finally reaching friendly shores was a god-send.

“It took us seven days, but we got there,” Vargas said. “Sicker than a dog, but we got there.”

Crossing Belgium would prove deceptively heartening. The recently liberated Belgians threw flowers at the American soldiers in thanks for pushing the Germans back. But as Vargas’ company approached the Rur River, he witnessed his first horrific scene of war.

“They had just finished the battle, still had a pontoon bridge built over the river,” Vargas said. “There were soldiers still lying dead on the beaches. Now that was shocking.”

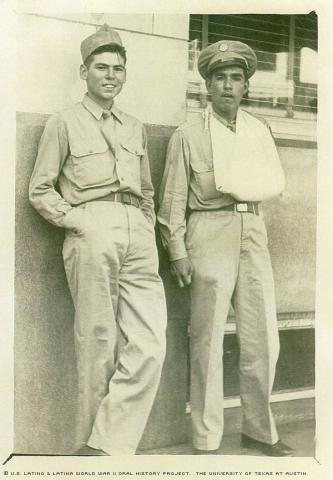

Vargas fought on the frontlines in the Rhineland. His service was cut short, however, when he was wounded March 3, 1945, during an engagement with German soldiers in the Hercynian Forest.

An explosion blew Vargas’ body under a nearby boxcar. He came to and couldn’t move; his body was frozen and his right arm was twisted behind his back. A quick check and he realized he didn’t have his weapon or helmet. He recalls laying there, waiting.

Mortar fire blanketed the area, lifting up clouds of dust and staining them a fiery red. Vargas could hear men around him screaming and moaning, calling out for help.

“I thought I was in hell,” he said. “There was this guy about 50 yards from me hollering, ‘God, somebody please help me.’ He was on his knees. I was froze; I couldn’t move. I think I fell asleep again and then when I woke up, he wasn’t there anymore.”

Vargas found out the war was over while en route from El Paso, Texas, to Brooke Convalescent Hospital in San Antonio. He was discharged Nov. 27, 1945, at the rank of Private.

During his time in the Army, he received the Purple Heart, a Good Conduct Medal, European African Middle Eastern Service Medal, American Theater Service Medal and World War II Victory Medal.

*********

Returning home to Fort Worth didn’t pan out as Vargas had envisioned. The war overseas was over, but a different sort of conflict was brewing on the home front: Social pressure between Latinos and whites was building.

Insistent on his getting an education, Vargas’ Veterans Affairs officer enrolled him at Texas Christian University. But Vargas felt unlike his fellow students, and very unwanted.

So he quit.

“I just didn’t like the way I was looked at and treated,” he said. “Things were not all that great for Hispanics back then.”

Vargas’ experiences in WWII prepared him to face the adversity of his upcoming years. Discrimination was just another word for battle, and he fought it whenever it reared its ugly head.

For example, he recalls being turned away from a bar in downtown Fort Worth. A board emblazoned with red letters read: “No Mexicans,” he said.

Together with five or six of his buddies, he recalls retaliating. Each man took two large rocks and pelted the building in the wee hours of the morning.

“We took the sign down and took it with us,” Vargas said. “When we got home, we tore it up in pieces and the next day we burned it up. A few days later, when the restaurant was fixed, we sent another guy in there to see if they would serve him. They served him.”

Mr. Vargas was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on September 15, 2007, by Jesse Herrera.