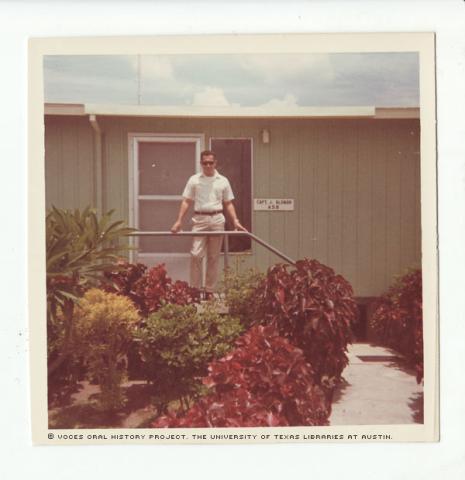

![Vietnam Vet, John Aleman, was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on April 9, 2011. [Voces Oral History Project/Michelle J Lojewski]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/IMG-897-03-600.jpg?itok=TtUoQGKA)

By Haley Dawson

When John Aleman became one of very few Latinos to graduate from Sam Houston State University in 1963, he not only overcame the poverty of his youth, but went on to succeed in his subsequent military service and post-Vietnam War community service. His Vietnam War duties as an officer in the courier service at Clark Air Base in the Philippines allowed him to see parts of the world he would never forget. But the experience also led him to conclude that the Vietnam War was unjustified, although the war posting allowed him and his wife to create a bond with the Filipino people.

Aleman was born in Waco, Texas, on June 23, 1940, to Pedro and Dolores Aleman. He spent most of his childhood in the rural town of Bellmead, four miles north of Waco. Aleman and his six older siblings for the most part attended school there, including La Vega High School, in Waco. When he was about nine years old, his family had lived in Marlin, Texas and for about a year, he attended a one-room schoolhouse there.

All of his time was spent at school and working to help support his family. With what little free time he had, he went to church and attended social functions through h St. Francis on The Brazos Catholic Church in Waco.

Aleman recalled that discrimination was a daily part of life in those days. In the world away from church and family, he saw that Hispanics were often excluded from activities and opportunities. He did not feel angry about his situation, however, because he knew no other way of life. He was able to transcend the discrimination by earning a college diploma.

Aleman attended Sam Houston State University from 1961 to 1963, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Printing and Graphic Arts with a concentration in business. As a Hispanic, he was in the minority on campus, and discrimination seemed just as present as it had been in high school. But he said that he had little time to dwell on it, because he was so busy. He took classes year round to save money and graduated in three years. He was eager to accept any job he could find, but when his draft number was called soon after graduation, he enlisted in the Air Force to avoid being drafted into the Army.

He was immediately sent to Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio for basic training. He remembered the conditions being rough. Like the rest of his life so far, there was no time for camaraderie or relationship-building with the other men because he was busy working all the time. His entry into the armed forces did, however, mark a drastic change in his life, he recalled. He was among few Latinos in basic training, and the only Latino left when he completed basic training and began officer training. He was surrounded by graduates from prestigious universities, such as Yale and Princeton. But, as a college graduate, he was afforded the same opportunities as everyone else, he added. Everyone was treated in the same manner, however harshly that may have been, and everyone was accorded the same amount of respect, regardless of their skin color, he recalled.

After training, he was stationed in Wichita Falls, Texas, for three years before he was deployed as a courier stationed at Clark Air Base in the Philippines. He only had one year left in his service, but the Air Force extended it so he could complete the assignment. His Air Force service lasted five years.

"That's the way the military is," Aleman said. "Whenever you have to go somewhere, they will send you, and it will be for the convenience of the Air Force."

Before he left for the Philippines, Aleman married his girlfriend of five years, Eugenia Gonzalez. The couple had met just after high school. She joined him on the base a year later, once he moved into a house of his own.

As a courier, Aleman received planes full of classified documents and equipment at the base, directed a team of men in unloading it, and then guarded the items until they were picked up again. He worked 24-hour shifts and often longer to complete inventory. He had two to three days off between shifts, but he was always on call; at times when they were short-staffed he might go days without sleeping.

"When you had to go on a flight to accompany material, you never knew when it was going to be," Aleman said. "You had to respond to any sudden need that was there at the courier station."

Aside from the long and rigorous working hours, he said that Clark Air Base was a good place to be. It was clean and relatively comfortable. As an officer, anything he needed was either already available or made available to him.

A few Filipinos lived on the base, and Aleman interacted with them often. He found the Filipinos he met to be easy to get along with and kind. He hired Filipinos to take care of his home on the base in an effort to support the local people and economy. He said that his wife befriended the Filipino wife of a GI, and the two couples spent much time together, while Eugenia took in the Filipino culture.

He and his wife traveled to Thailand, Hong Kong, and Japan when they could. They both recognized that Aleman's time in the service might be their only opportunity to do so.

"I said, 'If in our lifetime we ever hope to see these places, we better do it now, because later on we won't have a chance,' " Aleman said. "I'm glad that we did what we did."

He appreciated having had the opportunity to share his travel experiences with his wife.

Upon his return to the United States, however, Aleman encountered a harsh reality. Not only was he disrespected as a member of the U.S. armed forces and sometimes called names, such as "paid killer," but the freedoms and respect he had enjoyed as an officer in the Philippines were gone. He had re-entered a world where Latinos were often denied opportunities. He and his wife even had trouble renting a home. As an Air Force officer, Aleman found this humiliating and contrary to his idea of American culture.

Staying true to his values, however, Aleman did what he could with what he had. He wanted to help people realize their potential, just as he so hoped to do. So he worked as an interviewer and counselor for the Texas Employment Commission for 30 years, helping others find jobs.

Aleman also supported a number of organizations aimed at helping people. He was active in The American G.I. Forum and the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). He also co-founded the Latino Learning Center in Houston, Texas, to help Hispanic youth, although it was open to all. He recalled that he also co-established the first housing project in Houston run completely by Latinos.

In reflecting on his time in the military, Aleman recalled both positive and negative impressions. His experience as an officer helped him to grow as a person and gave him great confidence and strength during a formative time in his life. It also, however, put his life on hold for five years, thus setting back his career. As for the Vietnam War itself, he wished it had never happened. He felt compelled to serve his country when called to do so and did not blame anyone else for doing the same, but he believed the policymakers in Washington made a mistake by sending troops in the first place.

Aleman recalled an incident that drove this point home for him. While guarding 2,000 pounds of classified material one day on the sprawling base, he noticed a group of around 18 young Filipino men approaching him. They appeared hostile, so he nervously reached for his .45 caliber pistol, but realized that he did not have enough rounds to fully protect himself. Unsure of what to do, he reached in his pocket for a candy bar for a bite.

"Their eyes got big when they saw me with the candy. So I took the candy and threw it to them, and they ran, fighting for it. And I realized: They were hungry," he said, with tears in his eyes. "They thought the boxes I was sitting on were full of food."

Relieved to realize what they wanted, Aleman unzipped all his pockets and threw every last candy bar to the young men.

"I was thinking I was protecting my material," he said, shaking his head. "But that's what I was thinking.

"What were they thinking? They just wanted something to eat," he said.

Aleman concluded that his country was fighting in Vietnam a war against people who simply wanted to make it through the day, and it saddened him. He said the impact of Vietnam had been huge on him, as it was on everyone.

"You didn't have to go over there," Aleman said. "You just had to have one of your loved ones go over there, and the fact that he was there changed your life -- whether he came back or not." Aleman was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis a few years after his return from Clark Air Base.

"My return to the U.S.A. and civilian life was quite a contrast," Aleman said. "The reception for our troops returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, I applaud. ... I hope America never changes or forgets the sacrifice made by the entire family of the service person. It is hard on whole families. The support rendered by the families cannot be measured."

Despite the hardships he experienced, Aleman said he continued to be a positive, caring man, promoting excellence in all.

Mr. Aleman was interviewed by Haley Dawson in Houston on April 9, 2011.