By Kelsey M. Boudin

A single code word kept John Montenegro out of the Korean War.

He found himself heading out to sea aboard the USS General J. C. Breckinridge troop transport ship, just beyond the San Francisco harbor.

He and his fellow enlistees were each assigned one of two code words, "Dive" and "Evil." For Montenegro, "Dive" meant that he was to be stationed in Okinawa, Japan, for the next 18 months, until his discharge on June 15, 1954.

The "Evil" group was sent to the tail end of the fight against communism in Korea.

"I didn't have senses enough to be afraid. Put it that way," said Montenegro, who was 82 at the time of his interview. "I fully expected to go to Korea, but the Army had different plans for me. Once we got out of the harbor, we went under the San Francisco Bay Bridge. They called us back in the area for Dive, and they told us where we were going.

"I didn't have any idea where that was," he said. "But, either way, I was lucky."

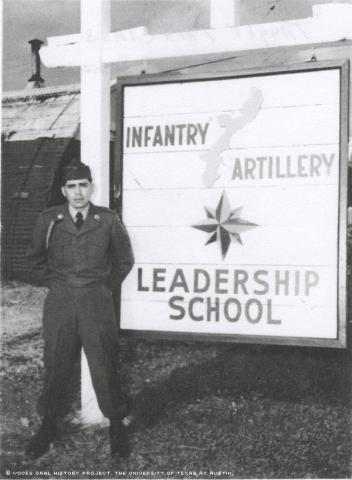

Montenegro took leadership training across the Pacific and as a private assumed command of a squad. During his year-and-a-half tour in Japan, he worked his way up to sergeant.

Montenegro, a native of Wichita, Kansas, had just graduated from high school when he joined the Kansas National Guard. When his four-year tour as a guardsman was up, he transferred to the active duty Army. He was assigned to the 29th Regimental Combat Team.

At the time of his interview, Montenegro could not hear well and had trouble speaking because of a battle with throat cancer. But in a muffled voice, he recalled his experiences as a young man who always followed orders and put his family and country first.

"I had one Hispanic from San Antonio. He went AWOL two or three times," Montenegro said. "I told [the company commander] 'I think I might know where he's at.' I knew he had a girlfriend.

"He told me to go check out a .45 [firearm] and a clip of ammunition and go see if I could find him," he added. "Oh, I found him."

His time in the military exposed Montenegro, who is of Latino descent, to a variety of cultures and ethnicities. But in his dealings with fellow servicemen, he said his eyes saw without color, even in a time of rampant racism in many American institutions.

"I had a white man clean the restrooms," he said, "and the black man, a corporal, I just had him make sure everything was clean. [The white serviceman] got mad and said, 'Why'd you pick me? That's a black man's job.' I said, 'I told you that you were gonna do it, and you're gonna do it.'

"I didn't like the idea of people being like that. We were all in the same boat. That was my opinion," he said.

At home, financial times were anything but easy for the Montenegro family. His father, who worked for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, often worked part time or was laid off, and his mother was unemployed.

While stationed in Okinawa, Montenegro sent home $40 or $50 out of each paycheck. The rest he saved until his release. He remembered leaving in June 1954 with a modest bankroll.

"At the end I had 300-and-some dollars," Montenegro said. "When I got out, the first thing I did was to buy myself a good camera. And, of course, I had to pay my way home … [Family] is where most of my money went."

But before his release, the Army offered Montenegro a promotion to work in intelligence. It didn't take too much consideration before he turned it down.

"They offered me a promotion, if I re-signed and returned," he said, "but I had already made up my mind."

Having just turned 25, Montenegro returned home. His job with the Santa Fe Railway awaited him, and there he stayed for 44 years of service until his retirement in 1990.

Mr. Montenegro was interviewed by Valerie Martinez on June 15, 2010, in Wichita, Kansas.