By Julie Rene Tran

The deep scar on his right arm, a slash made by a Viet Cong fighter’s knife, became barely visible. His eyebrows grew back and missing flesh on his calves, vestiges of a mortar attack, filled in. The upper lip, the one that “fluttered” after that same firefight, again formed a natural smile.

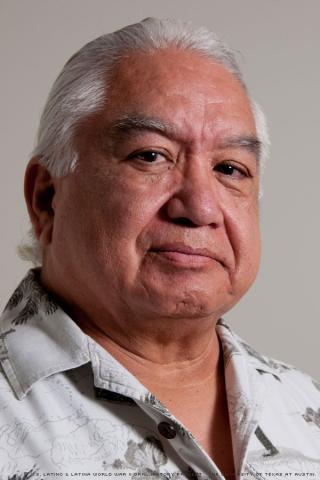

John Reyes Jr.’s physical marks from the Vietnam War healed; the profound impact of the war and life in the Marines weighed on him long afterward.

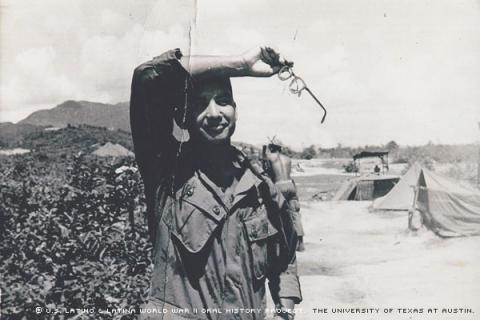

His prized artifacts include a five-pound marble elephant, shiny dog tags and an album of black and white photographs that Reyes took – all protected in a brown briefcase. They help tell his story.

A boy with four sisters in a middle-class family, Reyes was born in Houston Nov. 18, 1944. His middle-class family also included four sisters. His father, John Sr., was an Army veteran who had his own business, JR & Sons Delivery, a general delivery company whose contracts included NASA. His mother, Eleanor Gonzales, was a homemaker from Houston.

As an obedient teenager, Reyes recalled, he enjoyed running track and playing basketball at Hermann Park in Houston with his neighborhood friends. He was never the one to fall out of line with his father, and Reyes always kept the promise he made to his father never to smoke or drink alcohol.

Reyes always firmly believed in doing things right. His only defiance, perhaps, was in joining the Marines.

In his senior year at Jefferson Davis High school in 1964, Reyes dropped out and enlisted in the Marine Corps. Reyes joked that joining the Marines was his cowardly way of breaking up with his high school girlfriend. His father wanted him to finish high school first.

“I told my father ‘I don’t have the time, I have to go’,” he said.

Reyes had no idea that. halfway into his four years in the Marines he would ship out on a two-week voyage to a tropical country where he was told that touching young children’s heads was against the local customs.

Reyes had never heard of North and South Vietnam. He didn’t know where they were on the map. He didn’t even know a war was budding there.

“Vietnam was low on the horizon,” he said.

The Marines had trained him on the California-Nevada border for cold weather survival skills, such as skiing and trapping. Of course, those skills were useless in the lush, hot and humid Southeast Asia.

It wasn’t until the ship made a pit stop in Hawaii that Reyes said he had a clue where he was going.

Three older women with blue dyed hair, wives of officers, walking on the island greeted him with, “You must be the young fellas going to Vietnam.” Three days after departing Hawaii, the news was broadcasted to the ship, but Reyes already knew.

The convoy of four to six ships, the only ones to do a beach landing during the war, pulled up against the mountains of the naval base in the South Vietnamese coastal city of Qui Nhon. Snipers immediately began firing at them.

Reyes recalled that all he could think was to not get shot. Reyes’ luck held. No bullet ever struck him during his year in Vietnam.

His days in the tropical country were mostly monotonous, punctuated by monsoons and sweltering heat, he said. Rain or shine, Reyes spent countless hours at his post, which often was under a banana or rubber tree.

“I slept like a dog on the ground,” he said.

Assigned as a flamethrower, Reyes’ duty included gunning the weapon to release long streams of gas-fueled flames.

Reyes joked that the Marines chose him to be a flamethrower because he has a small brain capacity. The life expectancy of a flamethrower is three seconds, he said, because the enemy wants to knock you out fast.

“It’s a psychological weapon,” he said. “No one wants to be on the receiving end.”

But also laced in Reyes’ hard-knock life as a soldier were pleasant encounters, especially with the Vietnamese people. He grew to trust and befriend a communist-turned-ally Vietnamese soldier, whose name he only recalled as Cowboy. The man had a habit of handing Reyes rice balls to eat, one time one rice ball even had leeches he had burned off his legs. He also recalled drinking cool, bottled Cokes he received from the local women on laundry days. These rare, yet significant, interactions made Reyes’ brown eyes smile as he spoke of them.

The local children would run up to him, he said, and put their tanned arms next to his and say, “same, same.” Because of Reyes’ brown skin, almond shaped eyes and black hair, Reyes said he was often mistaken for a local. The South Vietnamese saw him as one of them, he said.

Even though he knew of a soldier who had bought custom-made Ku Klux Klan robes in Okinawa and sent them to his family as a joke, Reyes said the men in his unit were like his brothers and ironically, the crew nicknamed themselves as the Kool Kolored Kids.

“All that racial bullshit went out of the window,” he said.

Among the 22 men he had arrived with in his unit of the 1st Marine Division, 2nd Battalion, 7th Regiment, however, Reyes was only one of six that remained on active duty in South Vietnam by the time he left in 1967. Most got shipped out, others got malaria, and some were killed, he said.

Reyes was discharged from the Marines on Jan. 28, 1970. He earned a Good Conduct Medal, a National Defense Service Medal, a Vietnam Service Medal, a Vietnam Campaign Medal, and a Purple Heart.

He was awarded the Purple Heart for his torn lip when he was hit by mortars during the heavy fighting between North Vietnamese soldiers and the U.S. Marines in Operation Utah, which took place March 4 through 7, 1966. Reyes said that he had been shooting fire down one-man, camouflaged burrows to clear out anyone hiding in them one morning when the enemy shot mortars at him.

Instead of ducking in one direction to dodge the shells, Reyes went the opposite and got hit.

“You get the Purple Heart because you’re stupid,” Reyes said. “You zig when you’re supposed to zag, nothing to be proud of.” The attack singed off Reyes’ eyebrow, left him with open wounds on his calves and an upper lip that fluttered.

“Just superficial wounds,” Reyes said, adding that he was thankful because he could have gotten worse.

Ultimately, the war changed him.

Reyes said he was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and that it was hard for him to let people get close to him after the war.

Still, he earned his GED and owned two businesses. The first was a jewelry store and the second was as a driver of an 18-wheeler. He drove the semi-tractor trailer for about 15 years.

But he retired in 2008, after he suffered a stroke and spent time in a Veterans Affairs Hospital. He could not renew his commercial driver’s license because of his stroke.

The PTSD was hard to deal with initially, he said, and it became even harder as he grew older. But he just pushed through it on his own, he said, by reading lots of books and staying close to his children to maintain a steady and balanced life.

He was married to Carolyn Herina, for nine years. They had two children, Randi Renee Reyes and John Andrew Reyes. He then married Sheryl Smith in 1976, and they had two children, Haley Reyes Turner and Hillary Susan Reyes.

Despite the PTSD and the injuries, Reyes never regretted joining the Marines. He wouldn’t trade those four years for anything, he said.

“You could not do better,” Reyes said. “I’ve said this many, many times -- that you could not draw four years out of my life and [have] those four replace the years in the Marines Corps. That’s a fact.”

(Mr. Reyes was interviewed on April 8, 2011, in Houston by Julie Rene Tran.)