By Brigit Benestante

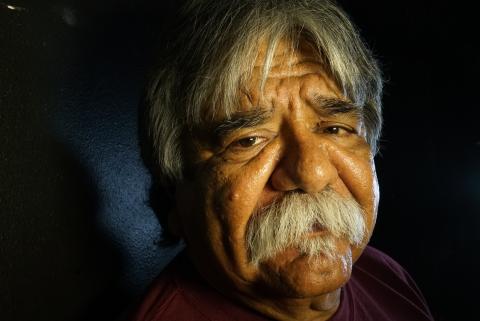

As a high school student in South Texas, José Aguilera participated in a six-week walkout that was ultimately unsuccessful and resulted in him leaving school. Yet he has no regrets: The experience defined him as someone who would stand up to the discrimination he had witnessed and felt.

“[The walkout] defined me as a person. I am really proud of that,” he wrote to the Voces Oral History Project.

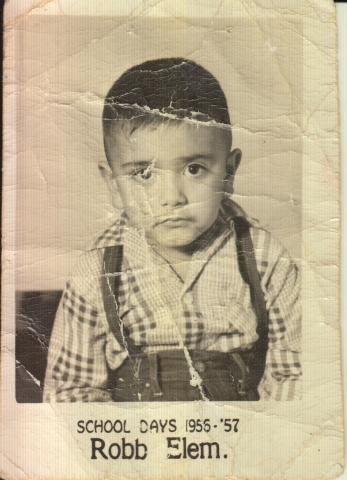

He was 5 years old when he accompanied his father to the polling location on Election Day in the small southern Texas town of Uvalde, 85 miles west of San Antonio. The two white men in front of them were greeted with warm handshakes from election officials, but when it came time for his father to vote, the response was different.

“They didn’t even shake his hand,” Aguilera said. “(The election official) just said, ‘It’s a dollar, señor.’ In other words, we had to pay a poll tax.”

From there, Aguilera said he became aware of the way he and other Mexican Americans were treated differently in Uvalde. He was forced to sit in the balcony of El Lasso movie theater, while white students were allowed to sit on the main floor, and his teacher punished him for speaking Spanish during recess.

“(One teacher) grabbed me by the ear, dragged me to a wall, and ... on the wall of the building she drew a circle,” Aguilera said. “She told me to put my nose on that circle. She drew it right at the height where I had to sort of tippy-toe to stay there, and I had to put my nose there as punishment for speaking Spanish. I was there for the whole half-hour we had for recess.”

In junior high, his football coach overheard Aguilera speak Spanish to a teammate and gave both boys two “licks” for their transgression.

Aguilera said experiences like those eventually motivated him to participate in the Uvalde High School walkout in April of 1970. The walkout, coordinated by Mexican-American community members and students, protested the lack of diversity among teachers and school board members. The protest lasted six weeks and resulted in the loss of a year of school credit for those students who participated.

“For a few of us, it went much further back than 1970,” Aguilera said. “We had this thing building up since we were kids. … It had to be done. One way or another it was going to have to be done. I saw the opportunity and all the stuff that had happened to me came together. And it was either now or never.”

Aguilera was born on Feb. 11, 1953, in McAllen, Texas. His father, Dolores Aguilera, worked as a mechanic, and his mother, Paula Hernandez Aguilera, worked as a cooks’ helper at a local restaurant. Aguilera served as the English translator for his parents. His father was expelled from school after he was blamed for a broken window. Unable to pay for the window, Dolores Aguilera was expelled. With a second-grade education, he helped to support his siblings without ever returning to school.

Aguilera said his father always told him that things would one day change.

Aguilera said his father always spoke up anytime anyone referred to a person with “blue eyes and yellow hair” as “el Americano.”

“’You don’t have to be guero and blue-eyed to be American. If you are born here, you are Americano. That’s what the Constitution says,’” Aguilera’s father would say, according to a statement Aguilera wrote to the Voces Project after his interview.

Aguilera’s father was his father when he was growing up, his teacher when he was a young man, and his best friend “forever.” He said his father always reminded him that he could accomplish anything and could succeed in anything he wanted to. His father passed away shortly before his college graduation in 1980.

“He was my best friend,” Aguilera said. “He taught me to always look at men in the eye and listen and feel with the heart, that the honor of a man was not found in conflict; it is found in the strength of handshakes,” he wrote.

One April morning in 1970, then a 17-year-old high school junior, Aguilera joined hundreds of students who walked out of class in protest. The night before, the students and community members had decided they would stage the walkout after George Garza, a teacher at Robb Elementary School, was fired at the Uvalde School Board meeting.

“It was all of this stuff I had gone through sort of came together (that morning): the poll tax thing, the little nose thing,” he said. “I didn’t want my kids to go through that.”

Aguilera said that even in conversations with his compadres about the walkout today, everyone gives a different reason for participating. According to Aguilera, there were rumblings of a possible walkout even before Garza was fired.

“The main thing that I remember, and why I got out ... is when Mr. Garza got discharged from his duties as a teacher,” he said. “The school board thought he was backing those who supported a (future) walkout.”

Two issues had finally come to a head in the community: the lack of Mexican-American teachers and the ban on speaking Spanish in school. The year before, the nearby town of Crystal City had staged a successful student walkout, and Aguilera said it inspired people in Uvalde to stage their own. The first day of the walkout, Aguilera walked home after protesting and denied his involvement in the protests to his mom. She wanted him to stay in school instead of protesting.

“That same day, San Antonio Channel 4 came out (to film the protest),” he said. “My mom turned on the news, and there I was, the first guy she saw. They were a little disappointed because they wanted me to graduate.”

After the first day of the walkout, Aguilera said he participated in marches in Uvalde and in the nearby towns of Eagle Pass and Del Rio, where similar concerns were being voiced. Aguilera said they were always peaceful in their protests, but Texas Rangers arrested him and his friends for demonstrating without a permit during a march in Del Rio.

“It was kind of fun (being arrested),” Aguilera said with a self-deprecating chuckle. “They gave us potato soup, but it wasn’t too good.”

After six weeks, Aguilera said, the protest failed. The Uvalde School Board did not meet any of the protesters’ demands, and students who had participated were forced to redo the school year. Aguilera, who played football and was recognized for his athletic skills with the nickname “Toro,” or bull, went to two-a-day workouts in preparation for the upcoming season. But he felt that players who had not participate in the walkout were treated differently than the players who had, and he quit football. In 1972, the Uvalde Coyotes went undefeated, winning the state championship.

“Politically, we lost,” Aguilera said. “I don’t think we gained anything politically, not at that moment.”

Aguilera doesn’t look at the walkout as a complete loss, though. He said his participation helped define him as a person. He said many people don’t agree with him; many people who participated think it “ruined” them. Aguilera said his experience in the walkout helped him adapt to life.

According to Aguilera, many of the boys who participated in the walkout had their names submitted to the draft board by the Uvalde School District.

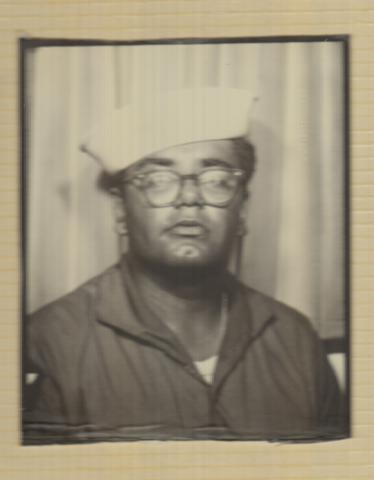

“(With the walkout) it was either ‘do or die’,” he said in a statement. “After all of it was over, I went into the service and I fell right in line there ‘cause that was their motto.”

Aguilera was first drafted into the Army but enlisted in the Navy instead. He went to boot camp at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in Illinois and volunteered for the Marine Corps after being stationed in Key West, Florida. He served on two ships -- the USS Saginaw (LST-1188) and the USS Guadalcanal LPH7 -- and was deployed to Guantanamo Bay, Puerto Rico and Jamaica. He was also assigned to the 10th Marine Regiment, 2nd Marine Division. It was the first time he’d ever left Texas.

“First time I’d ever been on an airplane. First time I’d ever seen snow stick to the ground,” he said. “When my four years were up, I couldn’t wait to get back to Texas.”

During his last year in the service, Aguilera took classes at East Carolina University. He was honorably discharged on June 4, 1976, at the rank of E5, with medals for sharpshooting with a .45-caliber and with a rifle. He also earned his Emergency Medical Technician certificate in North Carolina.

When he returned to Uvalde in 1976, he completed his associate’s degree in general education at Southwest Texas Junior College. He married Margarita Lopez on Dec. 19, 1976, and the couple had a daughter, Carina, the following year. Aguilera worked in various jobs back home: as a musician, a mechanic, a lumber salesman and a construction worker.

He said he sees a big change from how he was treated in school compared to how his grandchildren are treated.

“You can see some of the results,” he said. “Now, they’ve got bilingual classes. We didn’t have anything like that before.”

Aguilera remembers the discrimination he faced, but he also notices the abundance of Mexican-American teachers at the Uvalde schools today. He notices when he goes to the voting booth on Election Day and is not faced with a poll tax. The walkout was a crucial moment for him.

“I actually used the Constitution to express myself,” he said. "Even to this moment, after serving in the Navy, I see the American flag rise and -- golly -- I get a lump in my throat.”

Aguilera was interviewed by Raquel Garza in Uvalde, Texas, on April 9, 2016.

In a letter to the Voces Project, Aguilera said the following:

“Now in my 60’s, I somehow find time for the things I enjoy in life. I still live in the same house in the barrio I grew up. At times, I sit under that blackberry tree my mom and I planted a lifetime ago. I hear my grandkids playing as I once did as a kid. They don’t speak much Spanish like we didn’t speak much English growing up, yet, they sound happy as can be. They will never know the feelings I went through growing up. They may never see the face of being different like I did. They may never feel the anger of people who didn’t know better. Most people say we lost ‘the cause’ of the 1970 walkout, that it was all just a waste of time that left a scar that will never heal. Others don’t even want to remember, let alone talk about it. All generations encounter problems and dilemmas that they alone must resolve. We may have lost ‘the cause’ in 1970, but we did change a system in a time we believed it was wrong, and that was our victory. Our next generations, including my grandkids, will reflect and hopefully some day understand our sacrifice.”