By Peggy Hanley

Jose "Joe" Cuellar volunteered to be a scout in the South Pacific during World War II because scouts were considered leaders by his fellow soldiers. At the tender age of 18, Cuellar was convinced he wanted to be a leader, and being a scout fulfilled that yearning.

His desire to lead started developing at an early age, when he was forced to fend for himself and his family as a youth in Albuquerque, N.M. Cuellar says his strong work ethic helped him survive the experiences of war in the South Pacific.

Born in 1924, Cuellar lost his mother and an aunt to influenza shortly after his birth. He and his sister were raised by his grandparents and uncle in a two-room house in the village of Ranchos de Albuquerque in Bernalillo County, just seven miles from downtown Albuquerque.

The home the family lived in had no electricity or running water. To do laundry, they had to build a large fire in the yard and pump water by hand. After his grandmother passed away, Cuellar took over all of her household chores, including cooking and cleaning. He also helped his uncle, Santa Cruz Cuellar, manage the family farm by doing a number of tasks, including maintaining the horses.

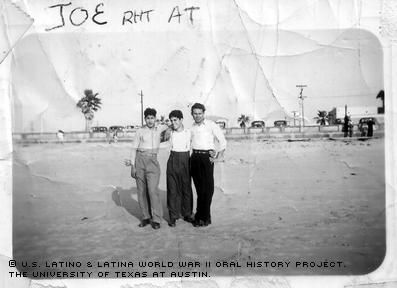

In the summer of 1940, at age 16, he ran away to San Diego, Calif., to seek work and a different life.

In San Diego, Cuellar found work on farms and tried to join the Marines. The Japanese had just hit Pearl Harbor and Cuellar knew he'd be in the service one way or another.

At 18, Cuellar was drafted into the Army and assigned to Fort MacArthur in San Pedro, Calif., in March of 1942. He was allowed two weeks leave to Albuquerque, where he met his first wife, Ella Mora, at a five-and-dime store. They’d write letters to one another for the duration of the war.

Cuellar returned to San Pedro for training, and then, along with 20,000 other troops, was shipped from San Francisco, Calif., on a converted luxury liner to New Caledonia in the South Pacific. He was placed in the Americal division, an Army infantry division formed in New Caledonia from the 164th Infantry Regiment from North Dakota, a regiment from Illinois and another from Massachusetts.

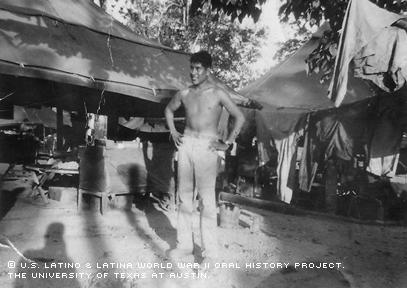

After his time in New Caledonia, Cuellar was sent to the island of Bougainville with the rest of the Americal Division. A friend from Waco, Texas, who the troops called "Tex," volunteered Cuellar to be a scout. They tracked Japanese movements and reported back to their commanding officers.

On their first scouting mission, Cuellar and Tex froze when they came upon a Japanese scout, who also froze in his tracks. No gunfire was exchanged, but Tex no longer wanted to be a scout. Cuellar, however, was both excited and motivated by the event, and was convinced he wanted to be a scout, a leader.

"A scout is a leader in any operation," Cuellar said. "I would volunteer to do that."

Cuellar eventually was promoted to Staff Sergeant, and the Americal Division saw considerable action in the South Pacific. Cuellar says he witnessed men die in battle almost every day and helped carry many out of combat areas.

As a scout, Cuellar liked finding his way in the night and had a good sense of direction. One night, he and other scouts followed some Japanese officers back to their camp and killed the men after watching them prepare their breakfast in the morning. When the war ended, Cuellar was on the island of Cebu in the Philippines. He says he learned much about himself during his time at war with the Japanese in the South Pacific. He returned to the U.S. feeling confident and proud about himself, bringing with him two Bronze Stars, a Presidential Citation Badge, an Asiatic Pacific Medal and a Good Conduct Medal.

"After I went to the service, nothing bothered me, because I knew I could do almost anything anybody else could," Cuellar said. "I got along with people."

After the war, on his way back home to New Mexico, Cuellar's train broke down in Los Angeles. He was reunited with Ella Mora, the young woman he’d met before the war, who’d moved to Los Angeles to work.

Cuellar returned home when the train was fixed. Ella joined him two weeks later and they were married March 8, 1946. Cuellar was 22 years old.

He began a new life in Albuquerque. He had a new wife, new home and, eventually, five children. One constant in Cuellar's life has been his ability to work hard. He held two or three jobs at a time to provide for his family. Before retiring, he had his own construction company and labored nights as a maintenance man for Sandia National Laboratories.

He’s now retired and living with his second wife, Delfina, on a ranch inherited from his uncle in Corales, N.M., a suburb of Albuquerque. Ella died in 1989 of lung cancer. Two years later, Cuellar lost his second son to influenza.

He says discrimination hasn’t played a major role in his life. He insists Latinos are just as good as others, but they must stick together and work hard. He offers hard-learned advice to younger Hispanics for the future.

"If they just put their mind to it, they can do it," Cuellar said.

Mr. Cuellar was interviewed in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on November 12, 2002, by Jennifer Sanchez.