By Lindsay Blau

Jose "Joe" Eriberto Adame saw combat in one of the most defining events of World War II -- the Battle of Normandy. But one of his most vivid memories is at the genesis of America's involvement in the conflict -- the day the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

"We heard on the radio that Pearl Harbor had been attacked or bombed," recalled Adame, who was a senior in high school. "Everybody knew that when the Japanese did the sneak attack, the United States would have to go to war and they did."

After serving almost three years in U.S. Army battalion units, fighting in France, Luxembourg, Belgium and Germany, Adame relished the end of the war and the opportunity to return to El Paso just in time for his younger sister's birthday. Although he didn't know it at the time, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the Americans would soon signal the end of the war and clear the way for his return home.

"When they dropped the second atomic bomb and I had about four to five days left and my sister's birthday was coming up," Adame said. "I wanted to be home."

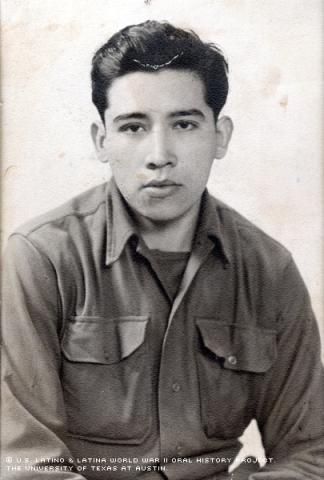

Adame was born to Mexican parents on March 22, 1922, in El Paso, Texas, the oldest of 10 children. Enlisting in the Army when he was 20 years old, Adame would serve in two units during the war: The 59th Signal Battalion, a nondivisional unit, and later, while in England, he served in Company C, 86th Chemical Mortar Battalion, which landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944.

Despite the bloodbath he saw at Normandy, Adame said he wouldn't change anything about his years as a soldier.

"I would do it over again," he said. "If I was 18 years old, I would go fight for the United States."

He said training and fighting for the war effort inculcated the importance of following and obeying orders, as well as the value of independence.

"The experience taught me how to do things for myself," Adame said. "Discipline is the one thing that makes a soldier or a soldier's life be good. The service changed me in a way that I enjoyed my family and home city more."

Leaving for Europe from New York in January of 1943 under a cloud of uncertainty and chaos offered Adame a different experience than when he returned almost a year later. By the time of his return, the Allied forces had defeated the Japanese to effectively end the war, and the mood in New York reflected that turn of events.

"I remember when we left it was real dark and the lights were dim," he said in remembering the day he was shipped off to war. "It was a sad situation. But coming back, all the lights were on in New York harbor and the place was beautiful and we were happy."

Awaiting the Normandy invasion, the 59th Signal battalion, with the rest of Eisenhower's invasion force, trained in England until June of 1944. Adame was later transferred to the 86th Chemical Mortar Battalion.

"We heard the news over the loud speaker system that the Allied forces under the direction of Gen. Eisenhower had landed in Normandy, France," Adame said.

His unit landed on Utah Beach in Normandy on June 6, 1944. He devoted three years of his life to the service and was honorably discharged on Oct. 10, 1945.

Many historians argue that Normandy was the turning point in WWII. While the ultimate decisive battle may be debated, historians agree that Normandy was one of the war's bloodiest fights. So many Americans lost their lives there, sections of Utah and Omaha beaches have been designated cemeteries honoring the dead.

In correspondence after his interview, Adame doesn't hide his stance on Normandy: "As we all know, the Battle of Normandy was the greatest invasion of all time," he writes. One would be hard-pressed to disagree.

Still, aside from the glory, his involvement in Normandy will haunt him forever, he said. A visit there on the recent 50-year anniversary of the battle brought Adame back to the site of the bloodbath he witnessed as a soldier. Nearly 60 years after his return to El Paso from Normandy, he still reflects on the loss of life. The tangible reminders of the bloodshed he saw at the 50-year commemoration -- the rows of cemetery plots -- reinforced that feeling of loss.

"All those young men who got buried in Omaha Beach Cemetery had no chance to learn what life was really about," he said. "The gravesites, you see them and you read the ages: 19, 20, 21, 22 years old," he said.

But the sacrifice abroad yielded positive changes back home, he noted. The GI Bill of Rights helped forge new career paths for Latino war veterans. Such opportunities were unheard of before the war.

"A lot of Latino war veterans started going to college," he said. "It changed the whole setup of El Paso in a way because more Hispanics were advancing."

Despite these strides, discrimination and prejudice were still endemic to El Paso, he said. Even though it was not overt, the bias was palpable.

"There were many people that would look at us in a strange way and they didn't say anything but we could sense it," Adame said.

Undeterred, he refused to allow discrimination to curb his love for El Paso, as well as his country in general. His roots in the Texas-Mexico border city are strong; the only time he left for an extended period of time was during his service in the war. He lives there to this day.

The opportunities granted through the GI Bill convinced Adame that education is the most powerful weapon against discrimination. He said today's generation of Latinos should arm themselves with the discipline of schooling.

"Young generations of Mexican Americans should strive for something they want to be some day," Adame said. "They should obey their parents. They should go to colleges or universities after high school."

He remembered his ethnicity being used by detractors as a slur. But he expressed pride in his dual heritage.

"They would call us Mexicans but we were not Mexicans," Adame said. "My parents are from Mexico [but] I was born here in El Paso. I am proud to be an American. I am proud to have done my country a service."

Mr. Adame was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on December 8, 2001, by Christina Perkins.