By Liliana Martinez

When Jose Guadalupe Garza was in the 9th grade in Brownsville, Texas, in 1937, his Anglo teacher asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up.

"I told her I wanted to be a lawyer, but she told me that I wanted to fly too high because that career required a lot of money and I didn't have it," Garza said. "I got discouraged so I got out of school."

At the age of 16, Garza left school to help his father with the 300-acre family farm, helping to harvest cotton, beans, corn, squash, onions and potatoes for about a year. But then he went to work for other farmers in El Carmen, Texas, about 9 miles from Brownsville, where he started earning 50 cents a day; within a few years, he was making up to $1.25 a day.

But little did Garza know, in July of 1942 his life would take a turn.

He was drafted into the U.S. Army, and he still remembers the day he got a notice saying he needed to go to the post office to be bused to San Antonio for a physical exam.

He was worried that day because he already knew he would pass it.

"I was sad because I was leaving my family," Garza said.

Garza remembers that during those days, the war seemed remote to most people, and he never thought he’d actually have to participate.

"There was very little communication for us in the paper and on radio," he said. "We knew that there was a war, but we really didn't pay attention."

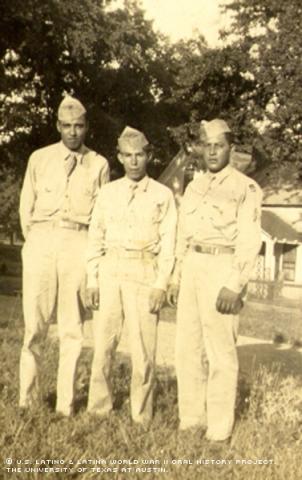

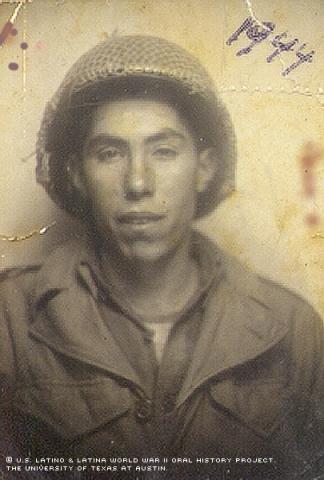

After he passed the physical exam, Garza married his longtime love, Concepción Garcia, on July 19, 1942, knowing he would be leaving soon. Two weeks later, he shipped out to basic training in San Antonio, made several stops at camps in Tennessee, Kansas, Arizona and New Jersey and, finally, departed for France via England in July of 1944. While in France, Garza started out as a light motor gunner operating a small artillery cylinder and firing ammo of 3" in diameter and 12" long. He recalled the sad incident that got him his sergeant position.

"In the first combat that we had, our sergeant went crazy," he said. "So they put me as a sergeant to guide the squad."

Garza would never forget his first combat, in which the men were outgunned.

"All we had was carbines, rifles and machine guns, but Germans had tanks with cannons," he said. "The only protection we had, which wasn't enough, was a pile of dirt. A bunch of dirt protects you from a bullet, but not from cannons.''

He recalls that hills were their nightmares every time they engaged in combat.

"We really didn't find much resistance in towns," Garza said. "It was in the hills, the Germans would bury themselves in the hills."

Although Garza was in constant danger, he was always protected. He carried a small statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe, a gift from his mother, before he left for war.

"I thought of my wife more than anybody else," he said. "I thought of my mom, my dad, my brothers, but more of her. I always thought what was going to become of her."

But Garza was wounded in his right leg after six months in combat. He was taken to a field hospital, where he remained for one day; then he was taken to a hospital in France, where he had surgery.

"They wanted to send me to London because they wanted to cut my leg," he said. The doctor told him that they had to wait 72 hours to make a final decision, and he says those were the longest 72 hours of his combat days. But Garza never gave up hope.

"I had nothing else to do but to pray [to] God that the medicine would work," he said.

Garza's leg got better and in a month he was back in combat. The war seemed tamer at that point, he said.

"When I went back, the Germans didn't fight a lot anymore," he said. "The [German] soldiers were very young and they were there not because they wanted, but because they forced them."

Garza considers himself a very lucky man who never gave up.

Although he was gone for three years and 11 months, he never lost contact with his family.

"I would communicate by letters or post cards," he said, adding that his letters were always short because he didn't have a lot of privacy while in the Army. "They censored my letters before I sent them, and they would read them before I got them, too.”

Garza also recalls he was the only Mexican American in the company, but the only discrimination he remembers was from his fellow soldiers who didn't like him because he had a higher rank than many of them.

"Even the captain told me, 'Take care of yourself, because there are some that want to harm you,'" he said. "I said, 'I want to go home. I don't care if they take away my position; they can hurt my record as long as they don't hurt my body.'"

After the war was over, Garza remembers the joy of touching U.S. soil again.

"I had done my part, and I said I was not going to go back again," he said.

Once back in 1945, he used the GI Bill of Rights to attend vocational school for four years and three months, and became a furniture repairman. After finishing vocational school, he decided to labor as a migrant worker, traveling throughout Indiana, Michigan, Montana and Wisconsin picking up tomatoes, corn, potatoes, cherries and strawberries.

In 1946, the couple's first child, Maria Perla Garza, was born and he continued working as a migrant worker.

In 1952, a second child, José Guadalupe Garza Jr., was born. Since Garza's job failed to provide a stable home for his family because they often moved from state to state, he decided to settle in Brownsville, Texas, and began working with the Brownsville Navigation District as a craftsman. After a few years, he moved up to Maintenance Superintendent, and after 31 years with the B.N.D., Garza retired on Dec. 31, 1986.

"It was not a lot of pay. They [his children] didn't have luxury, but they always had what to eat and what to wear," he said. "That's why I stayed here, so that my children would go to school."

Garza says he doesn't regret having gone to the war.

"I did something I was supposed to do as an American citizen. I defended my country and my family," he said.

However, he doesn't really like to think about his years in the service.

"I don't really talk about that, not even with my wife," he said. "I mean, it's not something pretty. It's something sad even though they were enemies ... but they were human beings."

"It's very sad when you see people without arms, because those bullets make such a terrible destruction," Garza said. "I have never forgotten that."

Yet, he says, he was doing his duty and is proud of that.

"I still think it was better that I went over there than them [the Nazis] coming over here to destroy our family and make a mess with women and children," he said. "I always thought, 'I'm just one of many [Americans] over there.'"

Mr. Garza was interviewed in Brownsville, Texas, on March 17, 2001, by Vanesa Salinas.