By Lynn Maguire

José Urías volunteered for tasks other men were loathe to do: combing the beaches of Normandy, littered with human remains; uncovering mines; going door-to-door in France in search of German soldiers hiding in private homes; and blowing up part of a castle that was a nest of enemy snipers.

Although Urías’ performance would earn him a Silver Star Medal and the admiration of his commanding officer and men, Urías says he was merely doing his job.

He worked hard to overcome obstacles. At age 14, he left his family in Arizona to find a well-paying job that would enable him to send money to his parents and 11 brothers and sisters back home. Urías, who goes by the nickname "Chuy," found work as a porter for 20th Century Fox in California and later at Capital Foundry, creating molds for copper miners back in Phoenix, Ariz.

Born Dec. 26, 1925, he was the third-oldest child in the family and stopped going to school in the sixth grade to help his father find work cutting grass. He describes his childhood as "constant work."

"School wasn't like it is now, you didn't have to go," Urías said. "Everyone had to work; you needed to work."

He remembers his school being integrated, and that sometimes other children would pay him money to defend and protect them when they were in a fight.

"I had a fight about every day," said Urías about his few years at Wilson School.

When he was 18, Urías was drafted as a private into Company "E" of the 355th Infantry Regiment, 89th Infantry Division. After his induction, he was sent to Camp Roberts in California for basic training.

There was racial tension during basic training, Urías says. He recalls being called a "wetback and Pancho," but says it didn't bother him. The white soldiers "came from across the ocean, [they] weren't any better then we are."

Later, in battle, there was no such discrimination.

"In combat you find out, ain't such thing as color,'' Urías said. "You didn't care what color he was."

After 17 weeks of basic training, he was sent to North Carolina and then Boston, Mass., before departing on Jan. 10, 1945, for Normandy, France.

"It took 14 or 15 days from Boston to hit Normandy, but it was already taken," Urías said. He arrived Jan. 24, 1945, six months after the D-Day invasion.

When he arrived on the shore of Normandy, he used his bayonet to scout for mines. When a land mine was found, he’d mark it with his bayonet, and another man would deactivate it so the heavy artillery was able to roll onto the beach.

One of his most heroic actions, one that won him the Silver Star Medal, occurred April 8, 1945. His assignment: to eliminate part of a castle in Germany, on the Rhine River. The enemy had been holding off U. S. soldiers.

"I was like a Christmas tree with grenades all over me," Urías said. "I would say 'cover me' and then I would run."

Three months later, on July 31, 1945, his commanding officer, Cpt. Herbert S. Lowe, gave his thanks for Urías’ actions:

"That your first consideration was for the safety and well being of your men was evidenced by the number of times you assumed the position of a 'scout' in spite of the personal dangers incurred and also by the judgment and intelligent caution you used on the approach march. ... By your own high standard of performance and conduct you have set an excellent soldierly example to your men which brought about a fine spirit in your squad and united them as a superior combat team."

At the time, Urías says he didn't comprehend the importance of the Silver Star. And he wasn’t that impressed with his own performance.

"I didn't feel like a hero," said Urías, who also earned Good Conduct and Victory medals. "It was a job, that's all."

He recalls hearing about the end of the war in Europe. Urías was preparing his men for the day when war prisoners came waving a white flag with their hands on top of their hands. Then an American soldier rode up on horseback crying, "The war is over, the war is over!"

It was 6:30 a.m., May 7, 1945.

"I just laid down in the street,'' Urías recalled. "I wanted just to sleep."

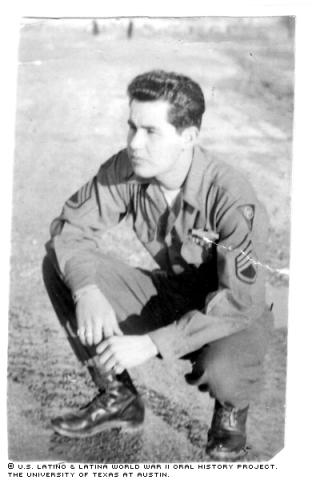

But there was still plenty to do. Urías was sent to work as an administrative noncommissioned officer, a "drill sergeant" in an Austrian concentration camp with prisoners of war. He was discharged about a year later at the rank of Staff Sergeant.

Urías returned to Arizona, bedeviled by demons.

"We were so young," he said. "We went and when we came back, I couldn't stand myself."

He overcame an alcohol dependence problem, spending time at a sister's farm for a year before getting his life in order.

He was finally able to taking welding classes under the GI Bill and then worked as an auto-body repairman.

He had five children; David, Diane, Daniel, Denise and Derek; with his first wife, Julia Soqui, and one child, David Jesus, with his second wife, Lucy Chávez Urías. His oldest son, David Urías, a paratrooper with the 101st Airborne Division, was killed in the Tet Offensive in Vietnam.

Urías resides in Scottsdale, Ariz., with his third wife, Emilia. He has eight grandchildren.

He notes that men who have experienced the horrors of war and suffer battle fatigue, or post-traumatic stress disorder, often marry several times. But despite its horrors, he says the war opened doors for Latinos.

"You can be anything you want in this country," Urías said.

Mr. Urías was interviewed in Phoenix, Arizona, on January 4, 2003, by Ismael Martinez.