By Cheryl Smith Kemp

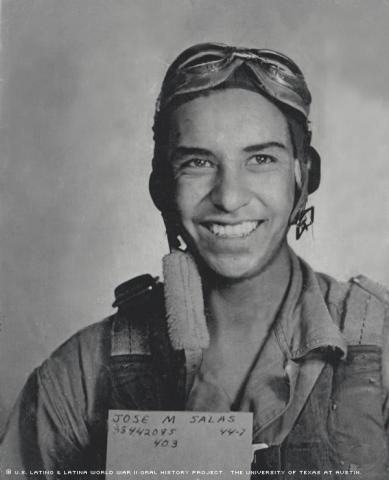

On July 25, 1944, with 160 hours of B-24 Liberator tail-gunner training under his belt, but no combat-flying experience, Jose M. Salas was picked to fill in with a crew for a flight from a United States base near Torretta, Italy, to Linz Austria.

“It was a very rough mission. We had a lot of enemy planes hit us,” recalled Salas, who was still a teenager at the time. “There was about 50 or so airplanes shot down that day. … I had six fighters shooting at my tail.”

Salas recalls passing out, then coming to with the plane on fire. Another member of the crew put it out with a fire extinguisher, then threw a parachute on Salas.

“I just put my feet out the escape hatch and I just pushed myself out,” said Salas, adding that the chute wouldn’t open at first.

When he landed, he hurt his lower left leg.

“[T]he bones came out, out of the wounds,” he said.

He spotted a two-story farm house about 300 yards away, the occupants of which were looking at him. But when he motioned at them, they went inside. Somehow, he managed to move closer to the structure, at which point a couple of young soldiers came out with cocked rifles. Instead of shooting, however, they lifted him onto a ladder and carried him into the house as if he were on a stretcher.

While in a bed upstairs, Salas recalls a German man who spoke English coming into the room and asking him a lot of questions, most of which he says he didn’t answer. Salas did reply, however, when the man inquired where he was from.

“New Mexico,” Salas said.

“We’re not at war with Mexico,” the man responded. “What the heck you doing here?”

Salas says he tried to explain that New Mexico is a state in the U.S., but the man wouldn’t listen.

“You’re not an American. What are you doing here?” Salas recalled him responding.

Not knowing yet that he was a prisoner of war, young Salas soon drifted asleep.

***********

As the baby of eight siblings, Salas had enjoyed a pleasant childhood in Santa Rita, N.M. His brothers and sisters working to help out his miner father, Jose C. Salas, and housewife mother, Juanita Munoz Salas, afforded Salas the luxury of being able to focus on school and recreation.

“I loved sports. I used to play a lot of handball, basketball, baseball,” Salas recalled. “We used to play with little automobiles, play hide and seek, different games.”

He remembers going on picnics on Sundays and staying up until midnight on Christmas Eve for mass, then coming home and having tamales.

Life got a little tougher when Salas started attending high school in nearby Hurley, however.

“It was kind of hard. I wasn’t too smart. I had to study quite a bit to keep my grades up. What I liked was sports,” said Salas, adding that he stopped playing them in high school due to discrimination against Latinos.

“The Spanish people had to be very, very good to be able to be on a team,” he said.

The Santa Rita area was quite segregated, Salas explains. The school buses were racially divided, as were the neighborhoods, cemetery and movie theater, he says.

Having dropped out of high school during his junior year, Salas was working as a trackman at the local Kennecott mine, “keep[ing] the tracks in good condition,” when he was drafted August 9, 1943.

Although Salas says he was limited to being a laborer at the mine -- the standard for Latinos working there in those days – he remembers passing every single test he took when he first entered the military. Uncle Sam gave him the choice of which branch to join as a result, Salas recalls, so he picked the Army Air Corps.

He went through basic training at Sheppard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas, then gunnery school in Harlingen, Texas, where he graduated as a B-24 Liberator tail gunner. The Corps then sent him to Salt Lake City, Utah, at which point he was assigned to a 10-man crew.

The men were sent to Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, for overseas training. Then they forged the seas to Italy, along with thousands of other military men, on the Santa Rita, which Salas recalls leaving from North Carolina. He remembers it taking about 16 days to get to Naples, Italy, and being assigned to the 764th Bomb Squadron, part of the 15th Air Force.

***********

After falling asleep and waking up a number of times, Salas found himself on an operating table in a hospital in Linz, Austria. He woke up to an old French man standing over him saying, “No tome tanto agua [Don’t drink so much water],” recalled Salas, who asked the man how he knew he spoke Spanish.

“You were cussing me up and down,” the man replied in Spanish.

After multiple hospital stays, infected wounds, a body cast, and, among other things, a brief friendship with a woman who Salas recalls claiming to be Hitler’s niece, the war ended while Salas was in a hospital in Waldorf, Austria.

He recalls a young German soldier arriving at the hospital on a motorcycle shortly after finding out the conflict was over. Salas says the young man was about to kill him and the other POW patients when everyone heard a loud noise, which scared the German off. Apparently an American tank had gotten lost, Salas recalls, and was at the front of the hospital. A couple of American trucks pulled up behind the tank, at which point the patients were set free.

Salas recalls helping gather up arms, then taking part in a raid of the facility’s wine cellar and celebrating victory.

The Red Cross came by the next day and Salas and the other patients were picked up within a few more days.

Salas remembers being taken to a couple of hospitals in Germany. Then, after a few days at the second hospital, he asked someone working there, “Say, what am I doing here? I was a prisoner of war. I was supposed to be flown to France.”

Later that day, an American officer came in Salas’ room and said, “Hey, you can speak English,” Salas recalled.

“And I said, yes, I was a prisoner of war.”

“And he said, good thing you told me that today, because you were gonna be shipped to India today.”

Fortunately for Salas, he was flown back to the States, where he was operated on in a hospital in Beaumont, Texas. He was officially discharged from the Army Air Corps on Nov. 23, 1945, at the rank of Sergeant. For his service, Salas earned the Purple Heart and a POW medal, among other honors.

Salas has lived in Bayard, N.M., for more than 50 years, and has been married to Consuelo Valerio Salas since 1955. They have three daughters, 11 grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. Salas is retired from the New Mexico Veterans Services Commission, after 28 years of service.

Mr. Salas was interviewed in Bayard, New Mexico, on April 30, 2008, by Robert Rivas.