By Iris Zubair

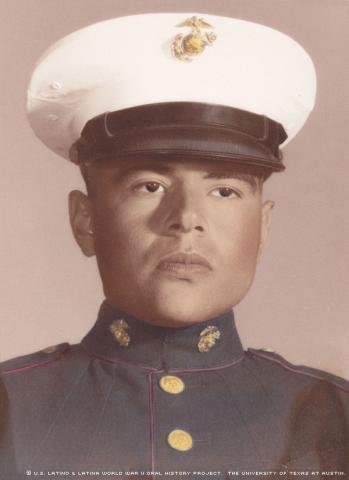

Although he had big dreams of a career playing football, Jose Mariano Soto, a young Mexican-American college student living in Laredo, Texas during the 1960s, volunteered for the Marine Corps to avoid getting drafted.

That was 1967. More than two years later, he was stationed with a Khe Sanh unit high in the mountain ranges of South Vietnam. He had little food or water, and he fought to survive. Soto remembered the long and treacherous 13 months of his deployment and the long-awaited news that he, along with most U.S. forces in Vietnam, would soon be going home. But even this good news was a double-edged sword to a young man trained to combat guerilla warfare.

“When you were getting short, that’s when you became afraid,” said Soto. “You became afraid that you were getting too close to come home. That’s when you get a little bit of fear. You start thinking about home and you’re not focusing at the things you can do best: staying alive. I remember that very clearly, the last two weeks. I was afraid. I was afraid more than the time before because I was getting too close, and you start losing that focus that kept you there alive.”

Soto grew up in Laredo with his parents, Jose Soto and Humberta Perez Soto, and his two older sisters, Elvira and Aida. Soto developed a passion for sports and athletics at an early age, taking a special interest in football. He played throughout high school. Soto lived the life of any average American citizen: playing football, hanging out with friends, working at Cabello’s Grocery Store during the summer months to earn extra money. It was his love of athletics that drew him to the Marine Corps.

“I always wanted to join the Marine Corps because of the unique form and because of all the propaganda that they only take the best,” said Soto. “I felt that I was a good candidate. I was in very good shape and I was very good in sports so I felt strong. Also, I was going to be drafted. I knew the draft was coming because I was not going to enroll in college. I already made up my mind that I wanted to serve and get it out of the way. So instead of getting drafted, I volunteered.”

So in October of 1967, 18-year-old Soto and his compadre, Hilario Riojas, talked about enlisted into the U.S. Army together under the buddy plan, but, Riojas’ brothers talked him into joining the Air Force instead, and the two friends traveled to their different boot camps.

“Boot camp was a very interesting 18 weeks in my life because they would work with you,” Soto said. “They wanted to mold you into a team. They train you so good and they kept you in very good shape. Boot camp was something that gives you a lot of discipline. They would work with your mind, they would be watching in other words. But it would prepare you for what was coming. It was the only way. I knew that if I was to have a chance at coming back from Vietnam, that was the branch of service [Marine Corps] that would bring me back.”

On Dec. 28 of the same year, just two months after arriving at boot camp, the Marines were given a leave to go home for the last time before deploying to Vietnam. The Marine Corps had plans for the newly trained volunteers to replace soldiers already stationed in the war region. After a brief stay at home, the soldiers returned to boot camp for another month or two of advanced training and survival tactics. Finally, after intensive military preparation, Soto was to be sent to Vietnam.

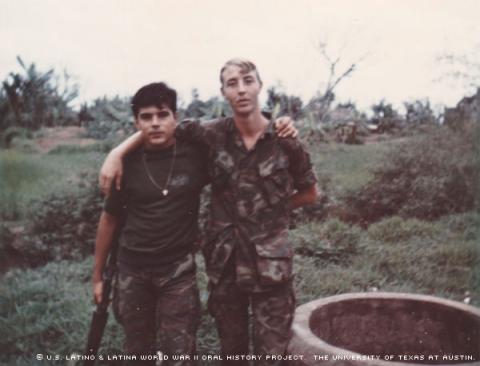

“Once we got to South Vietnam, I remember very clearly, going down the ladder,” said Soto. “It was during the daytime in Da Nang. As we were going down, there were people coming back and you could see on their faces that they had been in some place in hell. The thing that really got me thinking that I was in a very hostile area was that there were 20 body bags and they were American soldiers. I remember saying to myself, I am not going to die here.”

He was assigned to Quang Tri Province, serving with the 1st Italian 26 Marines, India Company, 3rd Battalion Marines.

Soto held onto his strength and optimism to get him through the horrific months that followed. He reminded himself to try to make it out of Vietnam alive every single day of his time there.

At barely 20 years of age, Soto found himself the target of many bullets, bombs, and multiple attacks. He recalled sadly the Easter Sunday they spent in the bunkers, where the troops were stationed to avoid being seen. Soto and his peers spent months hiding out in these bunkers where they were not allowed to use the bathroom during the daytime, there was no food, no water, and often times, the soldiers would spread what little peanut butter they had onto their arms so that the rats would eat it, causing the soldiers minor wounds. Any type of injury meant a trip to the base camp for treatment, which also meant a possibility to bathe.

Other challenges followed Soto’s stay in South Vietnam, including his station in the high mountains at Khe Sanh. Because of the monsoon season, there was no way for combat in the ground level, leading the infantry to be forced to stay in the colder temperatures of the mountains. The fight for survival was a constant hardship, as the soldiers worked on little food and sleep. Being stationary for too long meant certain death.

Soto reflected about his life’s journey as a young man from South Texas, who became even more fluent in English while in boot camp, and eventually even learned to speak a little Vietnamese.

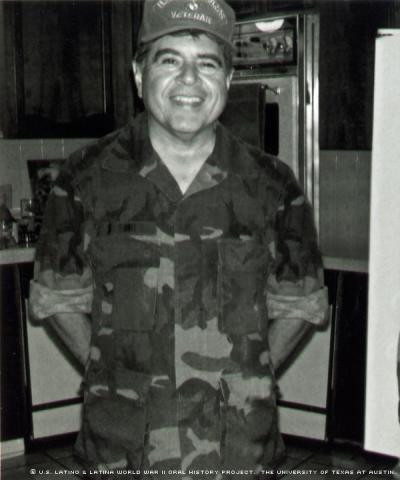

After his discharge, he went on to live a quiet and peaceful life at home in Laredo with his wife, Beatriz Adame Soto and their children _ daughter Belinda, and sons, Joey and Javier. He sometimes got together with his old friends from the war and laughed about their time in boot camp. Looking back on it, he could smile at the 18-year-old ambitious young man who volunteered to go to Vietnam.

Mr. Soto was interviewed on March 6, 2010 in Laredo, Texas by Liliana Rodriquez.