By Will Potter

Jose Ramirez remembers his first job: selling newspapers in downtown San Diego. After walking two miles home at the end of his first day of work, he proudly told his parents he earned 3 cents.

He was only 8 years old.

By the time he was 12, he was paying for his own clothing and some other expenses, so his parents wouldn’t have to support him as much. He worked to ease the burden on his parents so they could support his 10 siblings, he said.

But through his involvement in World War II, his perceptions of life in the barrio would drastically change. His experiences in Italy taught him about not only the benefits of living in America, but also the many opportunities for advancement.

His father, Marcelino Ramirez, completed only a few grades of elementary school. He did "pick and shovel work" for various companies in town and later learned carpentry and cement work. His mother, Soledad Villanueva-Ramirez, was a packer in the Sun Harbor Fish Cannery, where many other Latino women worked.

Ramirez remembers the frequent trek with his little red wagon to the surplus food distribution center to pick up surplus food for his family.

"They would give me turnips, oranges, some canned meat, which was actually horse meat," he said. "I don't eat turnips anymore, because I ate way too many in those days."

Ramirez worked through his last high school semester setting pins in a bowling alley and saved enough money to purchase his own suit for his San Diego High School graduation ceremony.

San Diego High School was primarily Anglo, but Ramirez said he didn't experience any harassment. He did recall more subtle discrimination, however. At the Fillmore, California, grammar school he attended briefly, Latino students were told not to speak Spanish. In San Diego high school, he says, students were told, "Don't bother going to college. You can't cut it there."

After high school, Ramirez enjoyed "getting together with the boys," going to dances and drinking beer. He stayed away from the Zoot Suit movement, which attracted Latino and African American youth, and avoided the fights that broke out between rival gangs. The Zoot Suiters were oftentimes regarded in the news media as troublemakers who challenged mainstream society. The "zoot suit" was a suit that consisted of outsized, padded shoulders and tapered slacks.

"I didn't like the way they carried on, quite frankly," he said, referring to the Zoot Suiters. "I couldn't understand it, and I saw no reason for it."

Instead, Ramirez stuck to a close group of five or six friends. When war broke out in Europe in 1939, they all knew they would eventually be drafted, he said, adding that after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the prospect of being drafted hit home.

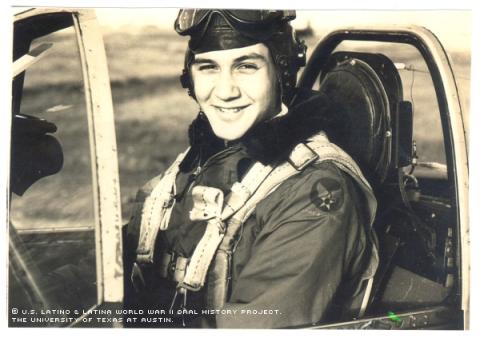

He enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1943 because "it was a matter of that or being drafted and not choosing which branch to go into," he said.

He served as a fighter pilot with the 15th Air Force, mainly in Italy. Most of Ramirez's missions were escorting bombers to targeted sites and providing defense against possible German attacks. Three squadrons of planes would fly above, below and parallel to the bombers, ready to ward off attacking planes and ensure a successful mission. The Germans never attacked, and despite flying 33 missions, Ramirez's only offensive maneuver was destroying a German locomotive in Italy.

Ramirez made it through the war without a scratch on him: His plane was never hit, never even shot at.

He was one of the lucky ones, he said.

"I'm a fatalist, a pessimist by nature," Ramirez said, "But not to the point I thought I would never go back [home]. I always knew I would."

Near the end of the war, oil shortages crippled the German air force, hindering their air presence. On the few days the Germans launched fighters, Ramirez was on the ground.

"I got over there too late to see a lot of action," said Ramirez, who received his assignment after the battle of Normandy.

But although Ramirez returned from the war physically unharmed, his personal outlook had changed.

"[Veterans] came back with our eyes open," he said. "When I went in, they must have been half closed."

Exposure to soldiers from across the country, and seeing poverty and depression in Italy, made Ramirez recognize the benefits of living in America, and made him decide to take advantage of it.

"We came back and we thought we were all entitled to a piece of the pie," he said. "We were not going to be satisfied living in the barrio. We felt we could get ahead, felt we had earned it."

After the war, he married Estreberta "Rachel" Gastelum on Dec. 30, 1949, and the couple had two children. Ramirez used the GI Bill of Rights to graduate from San Diego State College, later renamed San Diego State University. Then he worked for the state of California for 36 years, as an auditor and office manager for the California Employment Development Department.

Other returning Latino veterans took advantage of GI benefits assistance by learning trades or buying homes.

"We were dealing with a new kind of citizen," he said. "Veterans who had seen a lot came back, and were not going to take any crap. It was a turning point in the barrio."

Mr. Ramirez was interviewed in San Diego, California, on July 14, 2000, by Rene Zambrano.