By Jeff Jurica

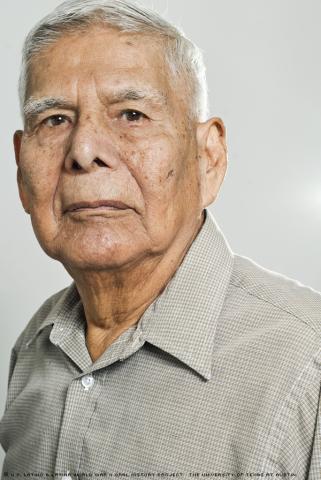

Jose Sanchez spent his life working hard in America's trenches. After serving in the Army during World War II, he returned home to start a plumbing business.

"All white people ... out of 500 soldiers I was the only Mexicano in that outfit," Sanchez said of his Army experience. "There were 10 Mexicanos when we were here at basic training. When we went across I was the only one." Despite cultural differences, Sanchez got along very well with fellow soldiers. "I remained good friends with several for life," he said.

A cannoneer in the 871st Field Artillery Battalion, Sanchez was known as a hard worker. Because he had an English-speaking background, Sanchez made friends, and he eventually held leadership positions over white and black soldiers of the same rank.

"I never got a rank ... but I always had people working under me," he said.

On Jan. 1, 1945, Sanchez's battalion departed London for the Atlantic coast. Sanchez was stationed in western France between two German submarine bases. "We were shooting the enemy all the time," he said. "Sometimes you got scared." But Sanchez found bravery in the friendships he made in his battalion. "We always stuck together," he said.

When the war ended in 1945, Sanchez was sent to an Army depot in Austria. He soon relocated to, what he calls "No Man's Land -- Germany."

"I was more afraid after the war than I was during the war," said Sanchez, whose first assignment in Germany was to patrol the streets of several small villages. "We were ordered to work in pairs. … We would patrol all day and night ... you'd better stay awake," he said with a smile.

After his job as a patrolman, Sanchez was re-stationed in Germany, at a campsite for captured German soldiers, and was assigned a position of authority. "After the war, we had a lot of German prisoners. … I was given two men -- one white, one black -- and we would march the prisoners from the army depot to the stockade," said Sanchez. "We would usually march up to 100 German prisoners at a time."

On May 22, 1946, Pfc. Sanchez was discharged from the Army and returned to the U.S. His service in war was over, but Sanchez had just begun working in the trenches.

He returned to Beeville, Texas, about 90 miles southeast of San Antonio. There, he found a job working at a feed store. On April 30, 1947, Sanchez married longtime neighbor Ernestina Zambrano. "I got back and she was still there," he laughed, "so I talked her into getting married."

Looking for better pay, he got a job working for a pipeline construction company. Sanchez had found his calling. "I got my master plumber's license ... and I started my own business: Sanchez Plumbing." Sanchez ran the family business for 50 years, doing jobs from Beeville to San Diego.

Sanchez credited his successful business to many of the skills he learned in the Army. “I learned a lot from the military ... I work hard, I don't stand or sit around talking or drinking water ... I keep working until I am finished," he said. The improvement of his English was his biggest take away. Sanchez said English was crucial to start his business. "I speak better English, write better English."

Sanchez was raised in a Spanish-speaking household in Sinton, Texas, a small town 28 miles northwest of Corpus Christi. There he attended an all-Latino school where he participated in academic competitions and played baseball with friends. After the sixth grade, Sanchez stopped attending school to help his father, Santiago Sanchez.

"Back in those days my dad used to take me out of school to go work," he said. Santiago drove his family to northern states, including Michigan and Ohio. As a migrant tomato picker, Sanchez also picked up English from his father and white farmers. His English became so good that, throughout his mid-teens, Sanchez translated English work orders to Spanish-speaking workers.

At the age of 16, Sanchez watched his older brother, Santiago Sanchez Jr., enlist in the Army. Inspired to fight for America, Sanchez attempted to join as well. "I went to enlist, and they told me to wait until I was 18," he said.

On Nov. 29, 1943, Sanchez turned 18 and enlisted in the Army. As he left for basic training, his mother, Visenta Salazar Sanchez, cried.

"In the Army, they gave you punishment if you were caught speaking Spanish," he said.Arriving for basic training at Fort Sam Houston, north of San Antonio, Sanchez was warned that Spanish speakers would be punished with orders to run laps while wearing their backpack. Sometimes "they would give you a restriction not to allow you out of camp."

After basic training, Sanchez lost any opportunities to speak Spanish. He never met any other Latinos in the Army. "I never saw another ... I looked for people to speak Spanish with, but I never found one," Sanchez said. "Spanish is important, but English was the key."

For his service in World War II, Mr. Sanchez was awarded one Bronze Star, a Good Conduct Medal, an EAME Theater Ribbon, and a World War II Victory Ribbon.

Mr. Sanchez was interviewed on Jan. 10, 2009, in Beeville, Texas, by Adolfo Dominguez.