By Prisilla Totiyapungprasert

Corporal Joseph Davila had a choice during his military occupation in the Southern Philippines: He could stay with the other soldiers to hold up enemy advancement toward American military headquarters, or he could race his way through an incoming banzai attack to rescue a fallen comrade.

It was 1944, a year before Japan surrendered to signal the end of World War II, and Sergeant David Fayard found his wounded, blood-covered body being pulled from the ground.

Davila had chosen to come back for him.

“I could hear enemies yelling all around,” said Davila, recalling slinging “Big Man,” or David, onto his shoulders.

It was a risky choice, but one that would save David’s life.

Davila is one of hundreds of thousands of Latinos who served in the military during WWII. The estimated number of Hispanics enlisted falls somewhere between 250, 000 and 500,000, though statistics remain hazy because the United States categorized Latinos as whites at that time, according to the National World War II Museum.

Davila replaced his labor tools with a rifle when he left Southern Pacific Railroad and was drafted Nov. 16, 1942. The San Antonio, Texas, native had already attempted to enlist earlier that year at a downtown recruitment office before he discovered his draft status.

Davila completed most of his training the following winter at Camp Lawton, slightly south of San Diego, Calif., before the military stationed him at Fort Lewis, near Seattle, Wash., where he was assigned to the 184th Infantry Regiment, Seventh Infantry Division.

Then, in May of 1943, Davila, a 20-year-old who had never been outside of North America, travelled to Kiska, an Aleutian island off of mainland Alaska, and Kwajalein, a part of the Eastern Mandates, where U.S. troops invaded Japanese bases. It had only taken a week to secure Kwajalein, and he had yet to come into close contact with the Japanese, but his next move, to the Philippines, would prove to be more trying.

As Davila and his battalion approached Panaon, a small island south off Leyte in the Philippines, he recalls noticing an unpleasant odor.

“The smell got stronger and stronger,” said Davila, as he described landing on the island.

They came upon a graveyard, at which point it became apparent that the stench was coming from the bodies of dead natives who had been killed by enemy forces.

Davila recalls the agony of entering a small church, where he found more bodies.

“One lady had her hand on a child,” he said. “They were slaughtered right there.”

It was a much more horrific scene than what Davila was used to before the war.

*********

As a child growing up in an impoverished, Latino-concentrated neighborhood during the Great Depression, Davila spent most of his time working to aid his struggling family. The second-oldest of four, he and his older half-brother, Manuel Martinez, made tortillas in a local grocery store in San Antonio. Other jobs included picking potatoes in the fields and bringing cows to pasture for Davila’s father, Leandro Davila – a chore Davila admits to having loathed.

Although the federal government handed out burlap sacks of food for relief aid, Davila says his family didn’t qualify, due to his father’s job at a flour mill. Davila attended Lanier High School for only a year before dropping out in 1936 to make working his top priority. He says he was surprised by how much money he made in the fields.

“I bought my first car when I was 14 years old,” Davila said. “I was the only one in the neighborhood.”

Soon, neighborhood friends began paying Davila quarters for gas to go on rides in his car. Davila also made money selling water at the local baseball field, where people paid a dime to watch a game through a peephole in the fence.

While laboring at Southern Pacific Railroad in the early 1940s, Davila says few people had radios or read the newspaper. He recalls news of the world-shaking events unfolding around them coming mostly through word-of-mouth.

“The war came and changed everything,” Davila said.

*********

In the Philippines, Davila’s platoon had initially come across deserted places, such as the island of Poro, where the enemy had already fled. He and the rest of his platoon then moved on to the semi-connected island of Pacijan, walking across the water when the tide was low.

The platoon came in contact with the enemy on the second day on the island. After chasing the opposing forces through a ravine, the GIs came across a hilly area that provided protection for the enemy. Some men in Davila’s platoon had already been wounded or killed, he recalls. Mosquitoes proved to be a constant source of agitation, though the GIs didn’t dare use repellent, as the strong scent would alert the enemy to their presence.

By the time Davila’s platoon decided to retreat temporarily, only 15 men remained.

After switching places with a full platoon to guard U.S. headquarters and allow the other platoon to fight in the hills, where the opposition was concentrated, Davila’s platoon broke into two groups to stand watch at two outposts situated outside the headquarters.

“They told us, ‘If you come in contact with the enemy, don’t do anything,’” Davila said.

Davila recalls the officers at their headquarters having instructed the platoon to call and warn them immediately if they came in contact with the enemy. Davila would later disobey these instructions, but for good reason, he says.

At the outpost, he and close friend Jose Flores settled into a routine. Flores dug the foxholes for them to sleep in and Davila set the booby traps, using biscuit tins attached to grenades.

The Japanese, who scouted the area at night, had already sent their commander maps of where the U.S. headquarters and tanks were located, Davila notes.

“The Japanese walked freely because they knew the island better than we did,” he said.

One night, as he and David stood guard, Davila’s ears picked up at the sound of stomping. A group of more than 100 Japanese soldiers was nearby and talking loudly; miraculously, they hadn’t discovered the outpost. Davila says he and David decided to hold off the Japanese on their own and slow them down, instead of alerting them of their still-undiscovered presence by making a phone call to officers of the 184th Infantry.

“The minute they got close, we started shooting,” Davila said. “It was the first time I had gotten so close.”

The Japanese wounded one of David’s men in the shoulder, who then, Davila recalls, proceeded to flee the attack. Other men, including Jose, followed suit, leaving only Davila and David behind.

Since it was difficult to see in the dark, Davila traded his rifle for the more effective grenade.

“I had never thrown so many hand grenades in my life,” he said.

When Davila and David finally decided to escape, David fell to the ground, proclaiming, “Joe, I’m shot.”

Davila hoisted the sergeant up on his shoulders and, as they left, a loud booming noise erupted. The Japanese had started a banzai attack.

*********

David may owe his life to Davila’s rescue, but it wasn’t the last time Davila would risk his life to go back for his fellow countrymen. On August 14, 1945, when Davila married pre-war sweetheart Helen Del Castillo in San Fernando Cathedral in San Antonio, he was wearing an arm sling, a sign of his still-recuperating body. The sling was far better, however, than the full body cast he had worn when he returned to the U.S. in April of 1945. Davila had spent 21 months in various hospitals, waiting on operations and recovering from wounds he suffered on Okinawa, where he had been blasted with bullets and fragments that had scattered from shrapnel projectiles.

During the Okinawa invasion in April of 1945, as U.S. forces began pulling back, Davila saw that one squad was too far up a hill to pull back with the rest of them. Once again, he decided to run back and help wounded men escape. This time, he wouldn’t get out unscathed.

As he darted between two Japanese front lines, he was hit in the leg. The shrapnel pieces caused nerve damage, resulting in his foot drooping. This time a different sergeant, Alvin E. Ellison, better known as “Elvin,” would come to his rescue. Davila recalls Elvin carrying him on his shoulders, as more motor shells struck Davila’s arm, and Elvin placing him inside a fox hole for protection.

“I was getting dizzy because I was losing a lot of blood,” Davila said.

Elvin didn’t survive Okinawa, a fate Davila says still saddens him. After the invasion was over, Davila was sent to a hospital in Guam, the first of many more hospitals to come. Corporal Davila was officially discharged Dec. 28, 1946.

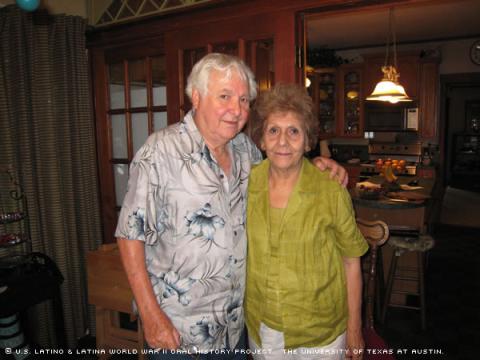

Now 87 years old and retired since 1977, Davila and Helen live more comfortably than their past permitted. Married for 64 years, Helen says they attend couples ballroom dancing at a continental club, where they salsa dance among Puerto Ricans, Cubans and Chileans.

Davila says Helen was 14 and he 19 when they fell in love after one of Davila’s friends asked him to participate in his wedding. Helen was the one who stood beside him at the wedding. Despite the strain of wartime distance, Davila says he wrote to Helen whenever time allowed.

“Dear John letters happened frequently,” said Davila, regarding break-up letters soldiers would receive from girlfriends and wives back home. “I didn’t know why they would cry; I didn’t know nothing about marriage. They would get really upset. I wondered why they would take it so hard. When I got married, I knew why.”

When he and Helen aren’t attending the Catholic church of St. Paul or hitting Louisiana casinos on the weekend for fun, Davila keeps up with a variety of national sports, including football, golf and baseball. Instead of selling water to baseball-game attendees, however, he follows the games of his two favorite teams – the Astros and Yankees.

“Now I tell people I want to get as much out of life that I can, because I’m running out of time,” said Davila, commenting on his age.

Coming out of the war, Davila says he received a disability pension of $90 a month for the loss of vision in his right eye. He used the money for the house he and Helen had been saving up for since his return.

“When we got the house, [Davila] had to work,” Helen said. “We had to fix it up. We would borrow money from his dad, $90 a month.”

Davila cashed each pension check to pay his father back, Helen says.

Before retiring, Davila used the G.I. Bill to attend a local technical school. He then continued his civil service, working on avionics for then-named Kelly Air Force Base. The family grew more affluent, sending their seven children to private schools and encouraging them to continue their education.

Davila says Latinos have done an excellent job making progress in the U.S. Although he isn’t actively involved in any Hispanic political groups, he commends the work activists have done and hopes to see more Latinos portrayed in the media.

For his courage and service during WWII, Davila received the Purple Heart, a Silver Star, Bronze Star, Philippine Liberation Ribbon with two Bronze Stars and several other awards.

“[The war] changed my life entirely,” Davila said. “We all say that if it hadn’t been for World War II, we wouldn’t know where we would be right now. It made the economy better. The Depression was just barely over. When the war came, it helped.”

Mr. Davila was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on June 20, 2007, by Joanne Rao Sanchez.