By Monica Rivera

When she was being trained as an airplane mechanic in the 1940s, Josephine Ledesma was the only woman in her training group. Later, as an airplane mechanic at Bergstrom Air Field, she was one of three women out of her seven-person workgroup.

One typical scenario was having several people working on one plane.

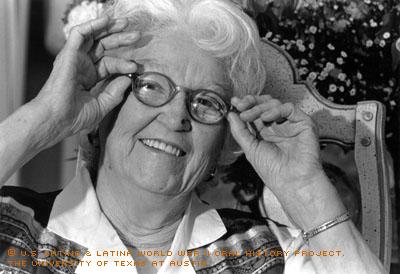

"You had people working on the electric part, on the hydraulic part, on the engine," said Ledesma during an interview at her home. "I happened to work on the fuselage, the body of the plane."

Ledesma, who was 24 when World War II broke out, worked as a mechanic between 1942 and 1944. In 1944, the United States produced 96,318 airplanes. Over 250,000 airplanes were produced between 1939 and 1945. Those airplanes needed mechanics.

"In Bergstrom Field our duty was 'to keep them flying.' We were taking care of all transit aircraft that came that needed repairs," she said.

During the war she volunteered to work as an airplane mechanic after her husband, Alfred, was drafted. When officials learned he was the father of a 5-year-old son, they waived his duty. But Ledesma had already signed up for a 6-month training class at Randolph Air Force Base, Texas. The couple's son, Alfred Jr., stayed in Austin with her mother and her sister in-law.

She learned to be a mechanic by practicing.

"Hands-on training or whatever they called it. You didn't sit in there reading books," she said. "You worked."

After Randolph Air Force Base she was sent to Bergstrom Air Field, and then to Big Spring, both also in Texas. She was the only Mexican American woman in Randolph Air Force Base. There were two other women, both Anglos, in Bergstrom Air Field, and several more in Big Spring, all working in the sheet metal department. At Big Spring, she was the only woman working in the hangar.

"I was the only Mexican American (woman) there," she said.

Ledesma enjoyed the two years she spent as an airplane mechanic.

"Oh, I loved it. I thought I was just doing a real big thing," she said.

But when the war was over she returned to her routine.

"After the war there was not anything like that. You had to put your mind to work at something else," she said.

She went back to her previous occupation as a sales clerk. Some jobs were off-limits to Mexican Americans. Before the war, she tried to find a job in a department store. The owner said he would be glad to give her a job if she used Kelly, her maiden name.

"You don't want to hear what I told him," she said. "But I didn't get the job."

That was not the only incident of racial discrimination she had to face. During the war, she and her husband, who was also working at Big Spring, went to a restaurant. After a few minutes they had to leave because the personnel refused to serve him.

"They would give me an order, but they wouldn't feed him," she said. "Big Spring was absolutely terrible with Mexican Americans and Blacks."

After she left the hangars she continued her role as a homemaker.

"This had been a job and that was all with it. So you went back to your own job: housekeeping and raising kids," she said. The war did not change that in her life. "I had my children to give me a full life."

She had four children. Alfred, the eldest, was born in 1937. Dolores was born in 1944, John in 1946, and Linda in 1948.

During the interview at her home in Austin, Texas, Ledesma recalled her own childhood with a smile. She grew up with her mother, Josephine Leonor Barrera, a schoolteacher, her father, John Arthur Kelly, a conductor for the Southern Pacific Railroad, and her grandparents in a country house in Kyle, Texas.

"There was a big fig tree on the outside of the window. And I remember till today the smell of that tree when I used to go to bed," she said. "The breeze was just wonderful at night. And we didn't have to have any air condition or anything like that."

She also remembered how her grandmother swept the floor and fed the chickens while her grandfather worked in the fields. They were farmers.

"My grandfather and grandmother always planted a garden, and during the Depression we didn't have any money but we had plenty to eat because we got it out of the garden," she said.

Ledesma, 83, who belongs to the Ladies of Charity and is the president of the senior community where she lives, believes that education is the only thing Mexican Americans can have to fight against discrimination and get equality.

"I really would like for the Mexican Americans girls and boys of today to get an education. We are not going to get [anywhere] unless we are educated," she said.