By Taylor Gantt

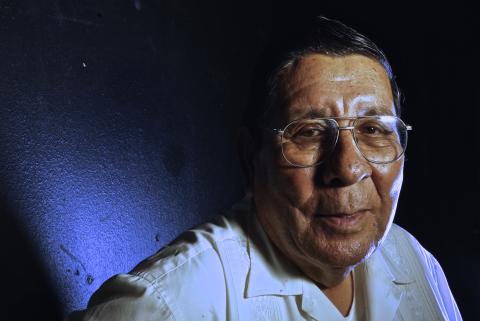

In 1970, George Garza was a popular middle school teacher in Uvalde, Texas. But when the school board repeatedly declined to renew his contract, he became a central figure in a six-week school walkout that changed the small town for generations.

These days, Garza downplays his own part in the walkout.

“That was like a climax to a chain of injustices that had been occurring,” he said in an interview. Mexican Americans were in a school system that practiced de facto segregation. “The younger people were kind of fed up, those coming back from Vietnam. (They said) ‘We’ve been fighting over there and getting shot at, and here we come to the same (discriminatory conditions).’ So there was a walkout.”

The majority of the population in Uvalde, Texas, a city about 80 miles southwest of San Antonio, was Mexican Americans; however, there were few in positions of authority. Garza was one of the few Mexican- American teachers. In the years leading up to the walkout, he became an intermediary for the Mexican-American parents in the segregated school.

“I was an advocate. Parents would come to me because of their lack of English, and I would go with them to the principal,” he said. “And I was acting like an assistant principal in a way and he (the principal) didn’t mind at first.”

It was not until Garza took graduate courses at Texas State University (then Southwest Texas State University) in San Marcos that the principal began to disapprove of Garza’s dedication and involvement within the school. The principal told Garza that he was “a double crosser” and assumed the only reason Garza would take graduate courses was to take the principal’s job.

Garza acknowledges that he was ambitious; his drive and ambition began when he was a child, selling oranges, apples and homemade tortillas door to door. By his early teens, he had his own newspaper route. He was a natural entrepreneur.

“My father always instilled in us a sense of salesmanship,” Garza said. “At the age of 13, I had my own business in Kingsville. I delivered newspapers. Delivered 500 papers a day.”

His father, Josue Rodriguez Garza, was a minister for a local church, the Mexican Assembly of God, a Pentecostal congregation. His mother, Luisa R. Flores, was a homemaker rearing the couple’s 10 children. The family moved around -- from Eagle Pass, where Garza started first grade, to San Antonio, then Kingsville from 1950 to 1955. They settled in Uvalde in January 1955.

Pastors of Mexican-American churches earned very little. “Moneywise, we were very poor since most church members were poor,” Garza said in a note to the Voces Project after his interview.

"But I did not think I was poor,” Garza said. “We didn’t have the best. My mother used to patch up our pants, and our good shoes we saved for Sunday mornings.”

Garza learned at a young age that he could make something of himself despite the odds. He was encouraged by a teacher at Gillett Junior High School in Kingsville: Gordon Trantt, an Anglo who spoke fluent Spanish.

“We’d all congregate around his room and he told me one time, ‘Look, you got two strikes against you: One, you’re poor and [Two] you’re Mexican,’” Garza recalled Trantt telling the Mexican-American children. “Get your education. Don’t quit school. Don’t quit school and get your education.’”

Trantt became a role model to Garza.

Much later, when he became a father and his own children were in school, he was called to meet with his son Ronnie’s teacher, who said the boy had disciplinary issues.

“’Well, what’s wrong with him?’” Garza asked the teacher. The answer: “’He’s a little bit cocky, like he’s high class.’”

Garza graduated from Uvalde High School in 1958 and joined the U.S. Army. He was sent for six months of training. Upon completion of that training, he began attending Southwest Texas Junior College in Uvalde. He had also joined the Army Reserves in 1956 and later was drafted in 1961, serving with the 49th Armored Division. He was discharged a year later, on Aug. 15, 1962, with the rank of E4. While he was on active duty, he married Rachel de Leon, on Dec. 29, 1961. The couple eventually had two sons.

After his discharge, he resumed his education, earning a bachelor’s degree from Texas A&M Kingsville (then called Texas College of Arts and Industries) in August 1964, while also serving as a teacher in Uvalde. He later became principal at a junior high in Crystal City, 39 miles south of Uvalde.

“We received numerous awards,” Garza said. “But my goal was to be superintendent. … That was the essence of my upbringing: Try to be the best.”

All the while, though, Garza wanted to teach in Uvalde, where his wife and children lived.

About a month later Garza filed to run for county judge, expecting that he would lose but hoping to get people to the polls. But not only did he lose the election, he was also notified by letter a few days later that he would not be recommended for another teaching contract. Garza was shocked.

“I was disappointed, and I went and talked to the superintendent,” he recalled.

The superintendent, though, left the decision to the principal, the man who believed that Garza was trying to take his job. Garza then appealed to the school board, which set a hearing, but one member was absent so they canceled the meeting.

“They said, ‘We don’t have a quorum,’” he said. “And we said, ‘Yes you do. Just say yes or no so we can proceed,’” Garza said.

“Words were exchanged between the board members and someone said, ‘Walk out. Let’s walk out,’” Garza recalled. And they did.

Five hundred to six hundred students, about half the student body, walked out, many attending “freedom schools,” or “huelga schools,” (strike schools). The protesters had meetings, strategizing about what they could do. The students stayed out for the rest of the year and were not given school credit for the year. But that was not the only action being taken: Garza and other educators took the next step and began speaking with the courts. One of the key activists was Genoveva Morales, a mother of 11 children.

“Mrs. Morales was a very brave woman. She filed the lawsuit in her name and we lost it. We knew we were going to lose,” Garza said. The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund appealed the failed lawsuit to the 5th Court of Appeals in New Orleans and the court reversed the ruling, so Uvalde had to integrate the schools.

“It was mandated that they hire school administrators, Hispanic school administrators,” he said.

Garza said most of the discrimination did indeed come from the administrators.

“The high school principal would make a list of all the graduates. The Mexicans, the Spanish surnames -- he would put ‘1A’ and the English names he would put ‘1S,’” Garza said. “It meant the ones that had an S, they’re going to college in September. And the ones with 1A are eligible for the draft, and so he would send that list to the draft board.”

Garza said people complained to the U.S. Department of Justice about the practice, and things began to change.

“That’s when they named Mr. [Rodolfo] Flores to the draft board because we had no representation,” Garza said. “Flores pushed for equality.”

Many years later, in 1989, he was hired by the Southwest Texas Junior College Adult Basic Education as a teacher and was eventually appointed director.

In his interview Garza credited a few key people for the success of progress in Uvalde.

“Mr. Gilbert Torres, a pioneer in the civil rights movement, and Mrs. Genoveva Morales,” Garza said. It was Morales who had “the strength to file a lawsuit and follow through with it.”

Garza said large numbers of individuals sacrificed and stood tall in the Uvalde movements. “See, everyone [helped], but these people stand out: Mr. Torres, Mrs. Morales and Mr. [Rodolfo] Flores.”

Garza was interviewed by Prakriti Bhardwaj, in Uvalde, Texas, on April 9, 2016.