By Lindsey Craun

As a child, Juan Carlos Gonzales felt destined to fight for his country. He grew up in a home surrounded by a father and four uncles who were World War II veterans, and he remembered feeling that patriotism and strategic instinct ran in his blood.

Gonzales was a soldier from the start, he said. As a child living in the small town of Sonora, Texas, he demonstrated every day an aptitude for what imagined a soldier’s life would be. He and his friends would “patrol” the expanse around Sonora, he remembered, dressed in camouflage and armed with BB guns and pellet guns.

Sometimes they would steal apricots from an old man’s tree, Gonzales said, and their “uniforms” concealed them in the brush. Other kids would also steal the fruit, he recalled, and the old man would shoot at them because he could see them.

Ranchers would be just as unfriendly, and Gonzales remembered the emotional rush he felt as they fired warning shots over the children’s heads as they “patrolled” their land.

"I had it in my mind that that's what I want to do. I like that kind of life," he said of his dream to someday be a soldier. He added later, “I already knew what being shot at was like.”

Nearly a decade later, on Sept. 23, 1965, Gonzales enlisted in the U.S. Army. He fought for two years in Vietnam.

After basic infantry training, Gonzales moved on to paratrooper training. He joined his friends to learn parachute rigging, not entirely sure what the duties entailed. Gonzales said he just wanted to fight and be near his friends.

Gonzales was assigned to the 173rd Airborne Brigade. When he arrived in Saigon, he was reassigned to the 1st Cavalry Division, and then was sent to a base camp in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. There, he packed parachutes, poured concrete and built new buildings for the base camp. “I was in the rear,” he wrote later, “and I hated it.” He said that he learned that “only the infantry, artillery and armor are the ones who do the fighting. … I thought that all soldiers fought!”

One day, Gonzales recalled, he walked past the company area for the Pathfinders, a special unit of paratroopers who guide helicopter assaults. He was intrigued.

Soon after that, Gonzales spent some off-time getting drunk with a sergeant. He admitted that he wanted to transfer to the special unit. “Speak to the captain,” the sergeant advised him.

Gonzales, encouraged, took a chance and visited the captain in command of his parachute rigging unit. Gonzales recalled with a smile what happened next: “I said to the captain, who was from Fort Worth [Texas], ‘Do you know who Henry B. Gonzales is?’ ”

The captain said that he did. Gonzales was a U.S. congressman from Texas.

Gonzales claimed to be the legislator’s nephew, who would report all the base’s supply and waste problems to the congressman if he wasn’t transferred to the Pathfinder unit.

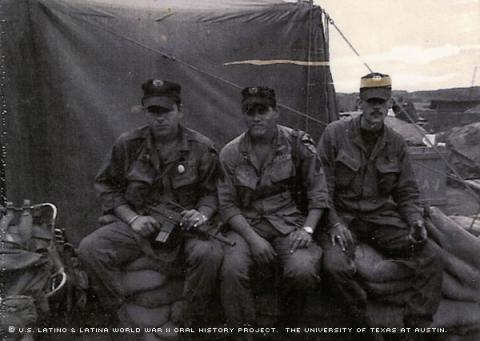

Gonzales said the captain immediately sent him to see a sergeant who could get the paperwork started. The transfer request was moved up the battalion chain of command, “and that same day,” Gonzales recalled, “I was in the field, sitting on top of a mountain with another Pathfinder.” Gonzales had been added to the 11th Pathfinder Company, 11th Aviation Group, 1st Cavalry Division, where he remembered receiving lots of “on-the-job training.”

“We were the eyes and ears of aviation on the ground,” he said. “When not out fighting with the line companies, we would go to a rear area to shower and rest.” While at the forward fire bases, Gonzales added later, they “would help out the helicopter door gunners who needed a break.”

When not resting, however, “we were almost always out in the field … active or breaking in new Pathfinders.”

In 1968, everything changed for Gonzales. The year began with the Tet Offensive, a surprise North Vietnamese attack on U.S. and South Vietnamese forces. Enveloped in the attack was the city of Hue. U.S. Marines launched a counterattack to regain the city, and Army forces, including Gonzales, were sent to support and then take over for them.

The 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, was sent in first. Its lead unit was Bravo Company, commanded by Capt. Howard Prince, who led it into the fight. “When they got to the tree line,” Gonzales recalled, “everything broke loose.” The Battle of Ti Ti Woods had begun.

Word soon crackled over the radios that U.S. soldiers were wounded and had to be evacuated. A mortar round had hit Prince and his team of radio operators. Gonzales stood up, ran across a clearing as snipers shot at him, and kneeled as he guided in a helicopter as close as possible to the wounded soldiers.

He grabbed the wounded men and loaded them on the chopper. One of them was Prince. The sight of Prince shocked Gonzales. He had spoken to the respected West Point graduate only the night before, and now he was placing his shattered, bloodied body onto a helicopter.

“I thought he was dead,” Gonzales remembered.

Thirty years later, Gonzales heard from his son, a soldier who lived in Fort Huachuca, Ariz. His son said he had just read a book about the battle for Hue, a book filled with the combat stories his father had shared with him all his life.

More importantly, his son told him that, according to the book, Capt. Prince had survived his battle wounds. Gonzales contacted the author, who put in him in touch with Prince.

“Saving a person’s life is something that is done without thinking of it,” Gonzales wrote later. “It is every soldier’s job to take care of their own. When I learned that he was alive, I felt good that what I had done had not been in vain.”

Prince -- who eventually made brigadier general, earned a doctorate in psychology and pioneered leadership teaching -- thanked Gonzales for saving his life.

Gonzales was later awarded a Bronze Star with V device (V for valor) for his heroism during the Tet Offensive. When recognized for his actions decades later at a convention for members of the 5th Battalion of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, Gonzales said he was simply doing his job.

Gonzales was also wounded during the Tet Offensive, but he was back in the field by early April 1968. That same month, just 13 days before Gonzales was scheduled to leave Vietnam for the U.S., his battalion and other units planned to assault A Shau Valley, which was also known as “Death Valley.” Their mission was to parachute in and assault an abandoned airstrip on the north end of the valley and turn it into a helicopter base.

Gonzales remembered feeling ready for a fight, but then his lieutenant, Jon Hergert, told him Gonzales was not going. Gonzales protested.

Gonzales said Lt. Hergert responded, “Sgt. Gonzales, it’s an order. You’re not going.” Just stay behind, Hergert added, and send the units any additional supplies, like smoke grenades or batteries, when requested.

Gonzales remembered feeling incredibly angry, not just on that day but for months and years afterward. “I wanted to make this assault!” he said.

What happened during the battle did little to comfort him. “That lieutenant,” he recalled later, “took five bullets on his left side.” Hergert survived, however, and Gonzales visited him when they were both back in the U.S., at Fort Benning, Ga.

A few years ago, Gonzales thanked Hergert for keeping him out of the fight that day. “I realized that I probably wouldn’t be alive today,” Gonzales admitted.

Gonzales returned to the U.S. on May 5, 1968, landing at Fort Lewis, Wash. Later in the day, he finally arrived in Sonora as the community celebrated Cinco de Mayo.

Gonzales began the final phase of his military career at Fort Benning, where, he wrote later, he was made an assistant instructor at the Pathfinder school and, after 60 parachute jumps, earned his Master Parachutist wings.

The Army, he recalled, “wanted to me re-enlist and attend Ranger School followed by Flight School. I would be going back to Vietnam as a helicopter pilot.” But Gonzales was ready to leave military service, and he declined the offer.

Gonzales was discharged in September 1968. His decorations included the Purple Heart, the Air Medal, a Presidential Unit Citation, the Vietnam Service Medal with four bronze service stars, the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Palm Unit Citation Badge, Master Parachutist wings, the Combat Infantryman Badge, Parachute Rigger Badge and the Pathfinder Badge.

In 1969, Gonzales married and started a family. He first met his wife, Lilia Perez, in elementary school in Sonora. They had two children, Emily Jane and John Carlos Gonzales. His family later grew to include five grandchildren.

After the Army, Gonzales first worked in construction. Later, he joined a surveying company, where he was offered the opportunity to attend Texas A&M University to study civil engineering. He earned a qualifying certificate and worked as a professional surveyor. His work kept him in Austin and Houston, where he worked on the cities’ airports. Later, he was elected a county commissioner in Sonora.

Gonzales also joined the Patriot Guard Riders, whose members, he explained, “attend the funeral services for fallen American heroes as invited guests of the family.” Their objectives are to show respect for the lost service members and to “shield the mourning families from interruptions created by a protestor or group of protestors … through strictly legal and non-violent means.”

Despite his personal and professional accomplishments, Gonzales admitted that it wasn’t an easy transition re-adjusting to civilian life, especially as he struggled with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. He remembered often waking during the night, screaming as though he was still fighting in the jungle. “Alcohol and drugs were a weekend getaway from my problems of PTSD,” he wrote later.In 2006, Gonzales added, he was “evaluated and determined to be 100% disabled due to multiple service-related conditions.”

Gonzales says he never forgets to pay tribute to his days at war. He and his veteran companions share a saying, “When were you at war?” one will ask. “Last night or yesterday,” he will respond. “We are at war every day.”

“Have to hang in there,” Gonzales said. “I am a warrior to the end.”

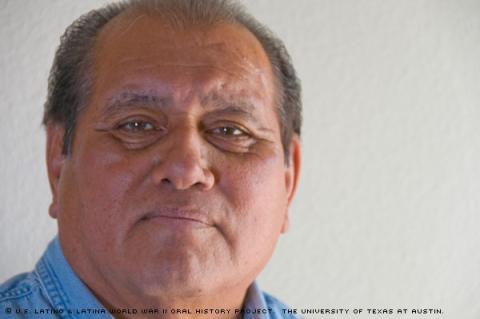

Mr. Gonzales was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on July 30, 2010, by Valerie Martinez.