By Frank Trejo

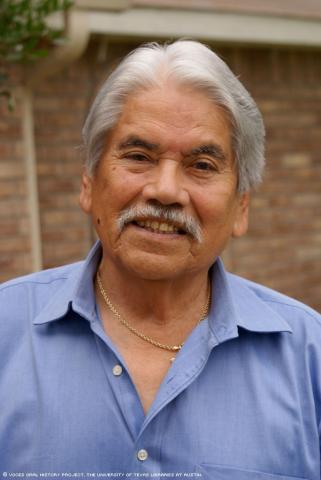

From childhood poverty in South Texas through the Battle of the Bulge, one of World War II's bloodiest conflicts, Juan Mejia proved he was a survivor.

Mejia's wartime experiences included being listed as missing-in-action for a time, but he said it never occurred to him that he might die.

"The closest I got was when a piece of shrapnel fell on me here on my coat," he said. "I just did this, brushed it off."

Mejia said the bomb exploded near a hospital in Belgium where he had been taken for treatment of "trench foot," a painful condition caused by having one's feet exposed to prolonged periods of moisture and cold temperatures.

It was that injury that led to his early departure from the battle front. But his experiences remained with him, and he always maintained that WWII and his military service changed his life.

Born on Sept. 13, 1925, in San Antonio, Mejia was one of nine children of Pedro and Cecilia Mejia. His father was a native of Leon, Guanajuato, Mexico, who had come to the United States during the Mexican Revolution. His mother was born in Zacatecas, Mexico. His father was a waiter and baker, while his mother was a homemaker.

They had five sons who served in the military. In addition to Juan Mejia, Salvador, served in WWII, and took part in three invasions: North Africa, Sicily and the Normandy D-Day landing.

"He was injured twice, but they would patch him up and send him back to the front," Juan Mejia said.

Another brother, Rodolfo, served in the Coast Guard, while Raul was in the Army in Korea and Gilbert served in Vietnam.

The family, Juan Mejia said, lived on a Texas ranch during his childhood. Even though the country was in the grip of the Great Depression, he has fond memories of that time.

"My childhood was beautiful," Mejia said. "We just worked and played with things around the ranch. There were always lots of activities. . . . My mother took great care of us and encouraged us to go to school."

He grew up in Thorndale, Texas, east of Austin, and attended Thorndale Elementary School. He never gave up on his education and finally earned his high school equivalency diploma in 1972.

But Mejia also recalled blatant discrimination against Latinos during his early years.

Because he spoke both English and Spanish, Mejia recalled that, starting when he was about six, he would serve as a translator for his father in all the family's business transactions. He said his father began working with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in a "good job" that paid $2.50 a day. That was a time when people were lucky to make 10 cents an hour, he said

"After my father started working for the WPA, we ate better; we lived better, and our lives changed more than anything after World War II, because then we all had work," Mejia said.

Before the war, Mejia, like others in his family had been a farm worker who traveled to West Texas and the Midwest. He was drafted into the Army in November 1943.

"I wanted to go into the Army to be able to get to know other people and get to know everything. I was very happy. We all wanted to serve our country, all of us," he said.

After basic training at Camp Shelby, near Hattiesburg, Miss., Mejia was sent to Massachusetts to await transport to Europe. He said he boarded the RMS Aquitania, an aging cruise liner being used to transport troops. It was a long trip to Scotland.

"What terrible food they gave us," he recalled. "The coffee was real bad, real bad, and for breakfast they gave us wieners."

But he said the soldiers received a warm welcome in the United Kingdom. From there it was on to the front and the December 1944 Battle of the Bulge.

He initially was in the 65th Infantry Division but was transferred to the 106th Infantry Division; Mejia said his unit was among those sent to reinforce the 2nd Division. He said they were told it was going to be much like guard duty.

"But the Germans came with all their artillery and with everything they had. Airplanes and everything, Mejia said. "I saw my friends on the ground, dead. They killed my lieutenant. The last time I saw my commander, he had a shot here in his throat, and there was a chaplain, kneeling, giving him his last rites. I remember that vividly."

He recalled that at one point, they had been dug into their foxholes when the captain told the men to rest before heading out again. Mejia said he was so exhausted that he slept for a while and when he woke up, he was alone.

"I just got up and went thataway, and went and went and went," he said. "Until I heard a voice, speaking English. And they were also lost." He was missing in action about eight to 10 hours.

During the time he was separated from his unit, Mejia's mother received two telegrams: one that he was missing in action and a second one almost a month later, telling her that he was OK but hospitalized somewhere in Europe.

He had been hospitalized, first in Belgium and then in England because of the condition of his feet. He returned to the U.S. in a convoy of Red Cross ships. Mejia said he was not in communication with his mother until after being discharged in July 1945 near San Antonio, at Brooke Army Medical Center in Fort Sam Houston. He took a bus home and rang the doorbell.

"My mother and father came out; they were both so happy," he said.

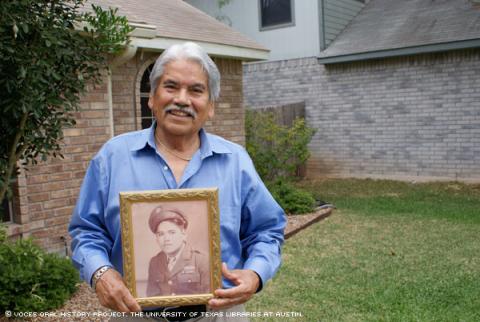

Among the medals and awards he earned for his service were the Bronze Star, the Combat Infantryman Badge, the Good Conduct Medal, and the European Theater of Operations Medal. Because of paperwork problems, he did not receive his Bronze Star until more than 50 years after his service.

After his discharge, Mejia said he received $300 and then received $20 a week for about a year. During that year, it was all he had to live on. He then got a job at Kelly Air Force Base, where he worked for 34 years until retirement. He said he received priority consideration for the job because he was a veteran and disabled. The base near San Antonio was subsequently closed in 2001.

"World War II opened doors for me; to be able to work for the government because I didn't have enough schooling, even though I didn't have experience," he said.

He married Enedina R. Mejia in 1948, and the couple had seven children; five daughters and two sons. His oldest daughter, Bertha, went to law school and became a first assistant city attorney in Houston, before being appointed as a judge.

His wife died in 2006.

Mejia said he led a blessed life. And, in looking back, he urged Latinos not to forget their roots.

"Always hold your head up high, and be proud of being Latino. And serve your country when you are called," he said.

He said World War II changed not only his life but the lives of many Latinos.

Before the war, he said, Latinos and all people of color experienced considerable discrimination. But things had changed after the war.

"People opened their eyes," he said. "If it hadn't been for World War II, who knows how we would be? It opened lots of doors."

Mr. Mejia was interviewed by Laura Barberena in San Antonio on May 11, 2011.