By Veronica Sainz

Raised with 11 sisters, four brothers and two pet javelinas in the small town of Chapin, Texas, no one could have guessed that Julian Gonzalez would become a decorated veteran of the Normandy invasion.

Gonzalez grew up on a farm where the only creatures hunted were doves or rabbits, and where the daily exchange involved tacos for sandwiches with a hint of World War II on the horizon.

Like many boys his age, Gonzalez says he was disenchanted with school.

"I used to hate it, especially studying English," he said. "For me as a Latin, learning English was hard."

His most vivid school memories are of Sister Mary Celestine, St. Joseph's principal. Gonzalez recalls getting called into her office on one occasion, and being scolded for having written "Viva Mexico" on the playground.

"She said, 'You like Mexico so much, why don't you go on the next train,'" he said.

When he wasn't at school, Gonzalez worked on his family's farm feeding animals and picking cotton.

"I was a good cotton picker," he said. "I used to pick 500 pounds of cotton a day at 50 cents a hundred; that was pretty good in those days."

In early 1940, Gonzalez finally left the farm and got a job working at Joe Stoppas restaurant, where he earned a dollar and a meal a day. In December of 1941, the nation was stunned by the Japanese attack on Peal Harbor.

Gonzalez remembers being caught up in the emotion.

"I was real mad. And I don't know, I was excited," he said.

Although there was a draft, Gonzalez didn't join the war effort until several months later. At the time, he was engaged to be married to a young woman named Leonor. One day, her father arrived from a neighboring town and took her away to be married to one of his friends.

Gonzalez says he went searching for her and found her in Mercedes, Texas.

"I told her, 'If you're happy, it's OK. I'll just go home,'" he recalled.

Although deeply saddened that day, he says an idea came to him.

"I thought, 'Hell, I'm going to join the Army and I'm going to teach this girl that I'm a man. I'm going to go out there and fight and come back a hero,'" Gonzalez said.

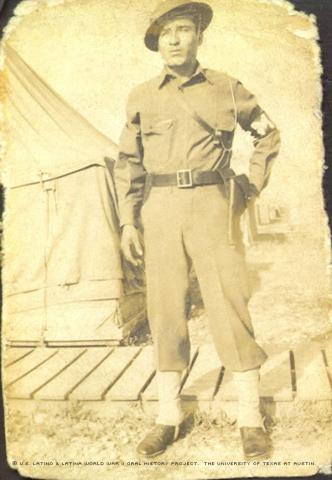

Sure enough, upon arriving home, he went to the courthouse and enlisted. In a short time he was sent to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, as part of the 2nd Infantry Division.

In October of 1943, his division set sail for Ireland. After 15 days of avoiding German U-boats at sea, his ship arrived in Belfast.

"They received us, the Irish, with a band, and they were playing 'The Yanks are coming,'" he said. "I was happy to hear them and yet I was sad because I had left my country and people behind."

The 2nd Division underwent grueling training maneuvers for seven months. Stationed in a castle, what leisure time they had was spent wandering through the musty room, torture chambers and underground passageways.

By 6:30 a.m. on June 6, 1944, the massive Operation Overlord, known as D-Day, was underway. The 1st Infantry Division and the 116th Regiment of the 29th Division made up the first wave of Allies to assault Omaha Beach. By the end of the day, Americans had suffered 2,400 casualties but had managed to land 34,000 troops.

Gonzalez's division arrived the following day. Their mission was to blast through the French hedgerows that separated property and to force the Germans to retreat.

"They never taught us to fight the kind of war we fought," Gonzalez said. "We fought that war in France where the terrain was not the same [as] the terrain they gave us in the States, not the same as the terrain they gave us in Ireland."

The task was difficult because the hedgerows often grew more than 5 feet in height and mixed with brush and trees; they also provided excellent cover for snipers and trip-wire landmines.

In St. Lo, Gonzalez says he witnessed a soldier cut down from nowhere. When he and another GI moved in to investigate, they found a woman with a rifle hiding in a wheelbarrow. The French wife of a German officer, she had stayed behind to protect the enemy retreat.

"We learned the hard way, by losing a lot of boys," said Gonzalez of sniper activity.

Fronts were extensively booby-trapped, and observation posts were set up along them at points where forward observers allowed the enemy to penetrate the lines before opening fire. They also patrolled deep into enemy lines on a daily basis and were successful in destroying isolated enemy forces and artillery pieces, Gonzalez says.

Gonzalez spent most of his time in France on these missions. In one instance, he says he defied the order of his commanding officer to lead his men across a field because a German machine gun was poised on the opposite end. He went alone along a hedgerow, trying to get close enough to throw a grenade. After tripping on a mine that miraculously didn't go off, Gonzalez successfully exploded the machine gun.

He recalls his men getting caught in an ambush on another occasion.

"They were screaming for help; a machine gun was spraying bullets from behind a hedgerow. I was responsible for their safety," he said.

Without a second thought, he says he charged forward, dropping a grenade at the base of the machine gun. Gonzalez says he then jumped the hedgerow, killing more Germans and disabling a rocket launcher.

Having fought without a rest for several months, Gonzalez says he grew tired of the war and prayed he’d be wounded so he could return home. Almost as if he’d been heard, a soldier next to him accidentally let off a round from his machine gun, which narrowly missed his toe.

They moved on to Belgium, where the streets were lined with cheering people and Belgian girls blowing kisses.

Gonzalez soon received an injury that would take him from the front lines: He stepped on a land mine.

"I didn't feel nothing on my foot," he said. "I got up and started walking."

His pants and his boot were soaked in blood. With toes missing and shrapnel riddled through his leg, doctors treated him on the front line.

Still in recuperation in a hospital in England, Gonzalez received the Distinguished Service Cross.

Returning from Europe in 1945, Gonzalez spent some time with his parents, taking odd jobs. He met Severa Treviño, whom he courted and later married. The couple lived with her parents and Gonzalez eventually settled into home remodeling. After about five years of marriage, his young wife died from tuberculosis.

Later, Gonzalez met and married Rosa De Rosa and helped raise her two children. The couple later had three children of their own: Nancy, Chris and Larry.

He became involved in the St. Vincent De Paul Society at his church and helped head up a troop of Boy Scouts.

Although he has never been published, Gonzalez can add poet to his list of life accomplishments. The first times of a poem he wrote are a tribute to those who served in WWII and capture the emotion he says has remained with him to this day:

"Sometimes I lay at night just thinking of that day...

The day I felt so scared...the day I got off the barge

To fall deep into the sea.

I walked off that barge thinking that land was there...

Instead I went under with the water above my head.

I swam and walked ahead.

I never felt so scared...so alone, amongst so many.

Days and months have gone by and so the years

But I still think of those boys that fell and didn't make it.

I pray for them, I talked to them and hope they are in a peaceful place"

Mr. Gonzalez was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on October 13, 2000, by Nancy Acosta.