By Raquel C. Garza

Julian L. Gonzalez didn’t walk the stage during the Thomas A. Edison graduation ceremonies in May of 1944. Instead, his father walked the stage in his place.

"It was announced that I wasn't there, that [my father] was receiving [my diploma] because I was in the service," Gonzalez said. "They told me that he got the biggest applause of anybody there."

Gonzalez had completed his high school education a semester early in order to be inducted into the armed services. He was inducted on March 20, 1944, at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas.

Gonzalez was stationed at three camps in the United States during the first eight months of his military career. While stationed at Camp Beale in California, the second of the three camps, he received his first war injury.

"We were sent up into the mountains of California to fight forest fires," Gonzalez said. "I was sent back to the base hospital [for a] ‘war’ casualty.

"I didn't get a Purple Heart for it," he added with a laugh. "I caught poison oak."

After being sent and released from the hospital, he was among approximately 25 soldiers sent to work shifts at the Del Monte Co. cannery in Sacramento. Gonzalez worked the graveyard shift, from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m., stacking cases of canned tomatoes in their warehouse and shipping department. It was tough physical labor.

After being sent to Camp Stoneman in Northern California, Gonzalez was sent to two cities in New Guinea. He was in Finschhafen before staying in Hollandia for 3 or 4 weeks; then he was shipped to the Philippines in December of 1944, where he served in a military government company, the Philippines Civil Affairs Unit # 10.

Before leaving California for the war front, Gonzalez recalled passing under the Golden Gate Bridge, thinking to himself, "No pierdo la esperanza de volver por aqui," or, I’m not losing hope of returning through here.

He was in charge of purifying the water supply, which was stored in an open cistern; in order to ensure its cleanliness, Gonzalez and a buddy would check the chlorine levels, adding the chemical as needed.

The job required the two men to set up camp at the site, taking measurements every hour. While he was positioned at that camp, Gonzales received his second "war wound."

"While I was in Mindanao, I should have gotten another Purple Heart ... I got stung by a centipede that big," said Gonzalez, holding his fingers 6 inches apart. "They warned us to shake your clothes before you'd put them on ... because of the insects."

But even though Gonzalez joked about his wounds, he spoke seriously about the fear he felt while camping by the water cistern. Rumor had it that some of the Muslims on Mindanao Island believed killing a Christian would lead to a meeting with their supreme being. Gonzalez didn't know whether the rumor was true -- he never heard of any soldiers being found dead. Yet it still made him worry.

"We hardly slept at night because we had fear of [them]," Gonzalez said.

But the ability to speak Spanish proved to be a useful skill to combat his fear of the Japanese. The Spanish language allowed Gonzalez to make friends with one of the leaders of the Spanish-speaking Philippine constabulary, who’d set up camp next to theirs.

"I made friends with the commanding officer because he spoke Spanish and I spoke Spanish. And I told him about our fear, and you know what he did? He posted a guard there 24 hours a day so nothing would happen to us," Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez was in Cotabato on Mindanao Island when he heard the war was over, after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

"At first, I thought it was just another bomb with high explosives," Gonzalez said. "But I couldn't comprehend the destruction of it until we saw pictures of it later."

After Japan's surrender, Gonzalez was reassigned to Manila, then Taejon, South Korea, south of Seoul. He spent six more months in Taejon before he was eligible to return home.

Gonzalez retired at the rank of Technical Corporal. The medals and decoration he earned included the Army Good Conduct Medal, Lapel Button Honorable Service, Victory World War II medal and Asiatic Pacific campaign medal with two bronze stars. He would also eventually receive the Philippine Liberation Medal from the Philippine government.

Gonzalez's hope of returning to the U.S. was realized when he was discharged on April 13, 1946. He came back to the U.S. by way of Seattle, Washington, and continued to his father's home in San Antonio by train.

On Sept. 9, 1947, he accepted a position with the Alamo Cement Company, where he worked as a timekeeper and in the accounts receivable office as an office manager. Five years before retirement, he was office manager for Midwestern Limestone Co., a subsidiary company.

After the war, Gonzalez resumed his friendship with Florence Gonzales, a childhood friend he first met at Hidalgo Elementary School. Although Florence was two years younger than Gonzalez, she caught up with him in the third grade after he was retained two grades because his English skills weren’t good enough to merit promotion. They continued their education together at Woodrow Wilson Junior High School, and then at Edison High School.

The two friends didn’t keep in touch after Gonzalez went into the service. But they were able to pick up where they left off and were married on Dec. 19, 1953.

During his high school years, Gonzalez aspired to be a social worker, but the war prevented him from going to college.

When he returned from the war, he took advantage of the GI Bill of Rights to pay for his college education. Under the GI Bill, the Department of Veterans Affairs paid up to a maximum of $500 a year for tuition, books, fees and other training costs.

Gonzalez attended San Antonio College while working full time for six years. He then continued his studies at St. Mary's University in San Antonio for eight years in order to get his degree in sociology.

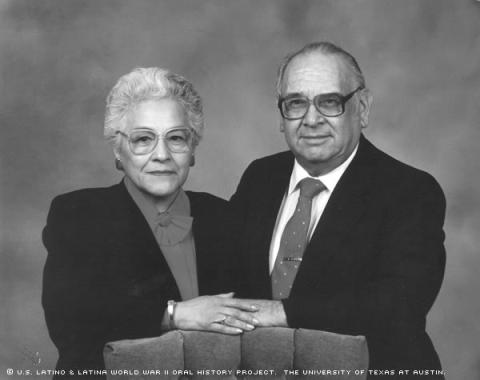

He now lives in San Antonio with Florence; they have three children, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Gonzalez said the war taught him to be more responsible as well as be a better citizen. It also taught him he’s an equal citizen.

"[Society] changed because the American GIs coming home saw what we did, they respected us more," he said.

To this day, Gonzalez harbors a great love for his country, instilling patriotism in his grandchildren, teaching them about the flag and talking to his grandson's Boy Scout troop about Veteran's Day. Gonzalez also demonstrated his patriotism by working in precincts for the Democratic Party.

"Love your country, be more patriotic. Learn more about the Great War and how it changed the country," said Gonzalez, giving his advice to younger generations.

Mr. Gonzalez was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on October 13, 2001, by Raquel C. Garza and Veronica Franco.