By Laura Radloff

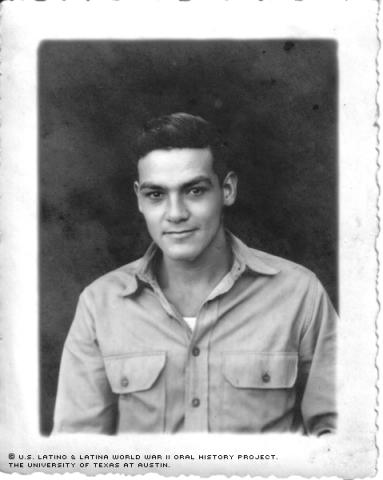

As a young man, Julius Casarez didn’t know exactly what he was getting himself into when he enlisted in the Army.

"My brother told me that if I enlisted sooner rather than later, I could pick where I wanted to be stationed," said Casarez, 82, who now lives with his wife, Trinity Castruita Casarez, in Austin, Texas.

Little did he know that when he enlisted, the Japanese were only a few days away from bombing Pearl Harbor, and he’d be forced to go where the Army told him to go.

As a young boy growing up in Austin, Casarez never dreamed he’d end up half way around the world, protecting his country. Casarez, the second youngest in a family of five children, was born in the United States. His parents, who were from Monterrey, immigrated to America after the Mexican Revolution. His father, Jessie Casarez, a police officer, and his mother, Maria Chavarria Casarez, saw that they could build a better life for their children in the United States.

Casarez has visited his parents' homeland several times, but he says he wouldn’t want to live there.

"They [Mexico] are about fifty years behind us. The rich are rich and the poor are poor. There is no in between," Casarez said.

Although his family wasn’t wealthy, Casarez says they didn’t lack for much. They lived in what was considered to be the country around Austin, so they had enough to eat from what they could grow. His parents worked for a dairy, supplying milk to the area. He and his brothers also hunted for food, Casarez says.

Jessie died when Casarez was in the fifth grade, so Casarez had to quit school in order to help support his large family. According to doctors, Jessie died from asthma, but, Casarez says it was most likely lung cancer that killed his father, as Jessie worked in a flour mill with no facial protection to keep him from breathing the dust.

After his father's death, Casarez worked selling newspapers, but he quickly changed jobs and began to work at the dairy until he was about 19 years old. During that time, his family was able to purchase a house in town.

Casarez later worked at a bakery located on Guadalupe Street. First, he was taught to clean the bakery, but eventually he actually did the baking. He worked there until the war started.

Casarez enlisted only a few days before Pearl Harbor was bombed. Right away, he was sent to boot camp in California, where, he says, his days were monotonous.

"In the Army, you get up at 5:30, then you go on hikes; 20 mile hikes, then more drills, then inspections," Casarez said.

One day the officers came around asking for volunteers to go on real duty. Casarez says he was so bored from the daily life of the Army that he was ready and willing to go anywhere.

"They didn't tell you where you were going, but I was tired of it, so I just volunteered," he said.

Casarez was sent to New Mexico to learn to use machine guns. In June of 1942, he was sent through Africa all the way to India, as part of the 703rd Special Forces, a machine-gun battalion.

In July, they crossed India, which was being bombed. Private Casarez and the rest of his unit served there a few months as machine gunners. Finally, they were sent over the Himalaya Mountains, and a month later the Japanese chased the Army unit out of China, where they’d been stationed.

"China was completely surrounded by the Japanese," Casarez said. "There was no way to get supplies to us except through Burma, which the Japanese also had control of."

Part of Casarez’s unit's duties while in Burma were to protect bridges that had recently been built as a way of transporting supplies to Army units. Casarez's unit would shoot at the Japanese planes that would try to bomb the bridges. Some of the time, they were able to shoot down Japanese aircraft.

Casarez finished out the war in the China-Burma-India Theater. He’d spent close to four years fighting not people, but "time and the elements," Casarez said. He and his unit were never given furlough, and Casarez didn’t have any contact with his family other than the letters he received once every two months, if he was lucky.

Finally, word came in 1945 that he could go home. Casarez recalls the captain of the unit, who was the highest-ranking officer, couldn’t arrange transportation out of the area. After about a month, his captain finally told the troops to "get out of here the best way you can."

So Casarez hitchhiked through China, where he was one of the lucky few who’d be able to take an airplane home.

Lucky, however, isn’t the word he uses to recount his trip home.

"I almost died three times," Casarez said. "First, in India we lost a tire when he hit the runway. Second, when we were flying over Africa in a two-engine plane, we lost one of the engines. And lastly, when we were near Puerto Rico, we had to fly through a tropical storm. The plane bounced all over the place."

Casarez says he was so happy when he got home to the U.S. that he never wanted to fly again.

"When I got off the plane in Florida, I kissed the ground," he said.

When Corporal Casarez was discharged in November of 1945, he was awarded a CBI medal and a Good Conduct Medal.

Casarez says he had to adjust a little when he got home. Although he never went through heavy combat like some soldiers, he says he still sometimes had nightmares about the war.

After returning to Austin, Casarez married Trinity Castruita. The couple moved several times in the next few years, seeking a better life for themselves and later for their six children: Albert, Maria, Anthony, Lawrence, Yvonne and George. After working several jobs in as many cities, Casarez attended an electronic school for former GIs. Finally, he and his family moved back to Austin in 1958, where he worked in the electronic organ business for 35 years before he went into semi-retirement.

Four years ago, a quadruple bypass forced Casarez to fully retire.

Now, his six grown children have careers of their own. A good education is one of the most important elements of creating a happy and successful life, Casarez says, and he made sure most of his children finished college.

Mr. Casarez was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on November 21, 2002, by Rasha Madkour.