By the Voces Staff

Lauro Castillo grew up in a poor farming family in South Texas, living in a bare-bones house with a leaky roof.

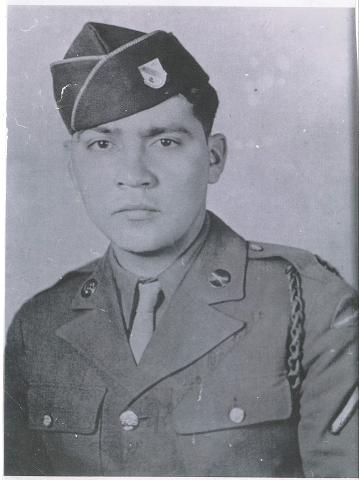

The U.S. Army provided an escape from poverty but also exposed him to the brutal reality of war. He was an infantryman in some of the toughest battles of World War II.

To Castillo, it was simply a matter of doing his duty for his country.

“I’m proud” of serving, he said. “I fulfilled my obligation to the U.S.”

Castillo was born on Aug. 18, 1922, in Bishop, Texas, a rural town about 30 miles southwest of Corpus Christi, and later lived in nearby Robstown. He was the oldest of three children born to Aurelio Castillo and Pabla Sanchez Castillo, immigrants from Mexico.

The family struggled economically.

During the Great Depression, “We did without new clothes and toys. We just couldn’t afford nothing, not even shoes,” he said. “We were extremely poor.”

Castillo helped take care of his younger sisters, Teodora and Tomasa, but had no friends of his own.

“I was a lonely boy -- no company to play with until I went to school,” he said. “And I loved school. I felt like I had a lot of brothers and sisters to play with.”

His elementary school teachers were kind and encouraging; he liked history and math and always got top grades in handwriting.

High school was a different story.

“I was going out to work in the field and missed a lot of school, and it hurt me.” He had to drop out to help support his family.

When the Pearl Harbor attack happened in 1941, Castillo knew he would eventually be called to serve. On Feb. 24, 1943, the Army drafted him. He was 20 years old.

Castillo said his parents were against their only son going to war. “‘No, no, no. If you go, what are we going to do when we get old? Especially if you get killed,’” Castillo remembered them saying. “But I wanted to go and experience. And I’m glad I did.”

He was sent to Camp Butner, North Carolina, for training; he said there were perhaps 1,500 Latinos there.

“I loved it,” he said. “At home at the time, I didn’t have water, light, gas, refrigerator -- nothing. When I went into the service, I felt like a rich man -- good food, hot water, no leak in the roof.”

He gained almost 30 pounds in six months, thanks to three square meals a day.

He was first assigned to the Cannon Company, 109th Infantry Regiment, 69th Infantry Division. When he got to England, he was transferred to the Headquarters Company, 3rd Infantry Battalion, 41st Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Armored Division.

He would see action in France, Holland and Germany, from August 1944 to April 1945.

Life on the march was rough. “You’re out in the brush, sleeping on the cold, wet ground. Sometimes -- with no weatherman to predict -- you get rain, cold,” Castillo said.

There was only a little more protection inside a tank: The hatch would leak when it rained, and there was no way to stretch out to sleep.

“You suffered when you were out in the field. I’m not bragging, but I was there.”

Castillo fought in some of the biggest conflicts of the war, including the Battle of the Bulge, in the Ardennes region of France, where Allied forces suffered high casualties.

“I was in the thickest of the war,” he said. “Battle of the Bulge: I was there from the beginning to the end.”

The event that sticks in his memory occurred in Germany, in an area about 80 miles from Berlin. Castillo and his fellow soldiers were walking alongside a tank when German troops opened fire, from hiding places in the brush and from a high hill.

Some infantrymen had jumped on top of the tanks for a ride. “They got bumped off; I saw about six that got hit,” Castillo said. He saw an officer go down, and called for another soldier to help drag the man to safety in a ditch, but it was too late. “Blood was coming out of his ears and nose. I saw that he was gone.”

A colonel ordered the soldiers to move ahead slowly, and then open fire with all of their weapons. They went about 600 yards before the Germans started firing again. They could not tell where the bullets were coming from.

“We started crawling” in a muddy ditch. Castillo said. “Every time we moved, we got shot at. It took us three and a half hours for 150 yards, moving two, three feet at a time.”

He and another soldier finally reached a house where American soldiers were inside. “They were happy to see us; they thought we were MIA.”

Castillo said the soldiers stripped off their wet clothes and gave them dry garments. After hot baths, they got a good meal and the first coffee Castillo had tasted in several months.

“I’ll never forget the date: April 3, 1945,” Castillo said.

After his discharge on Dec. 12, 1945, he returned to Texas and a country where segregation was beginning to fade.

Castillo said Latinos experienced segregation before the war, but whites began to treat them as equals after the war.

“There were places you couldn’t go in (before the war). You couldn't go into a barbershop, a theater. You couldn’t go into but three coffee shops here and there,” he said. “After the war they began to treat us as equal … and they took down those signs. We could go into places. But before that, restaurants: ‘No Mexicans Allowed,’” Castillo said.

Post-war life for Castillo also included further education.

“I finished high school. So I can’t complain,” Castillo said.

He worked for Texaco in Corpus Christi for 30 years, working his way up from deliveryman to manager. He then worked as a bus driver for the Nueces County Transportation Co.

On April 30, 1948, he married Guadalupe Duran. The couple had seven sons and five daughters: Fela; Martina; Lauro Jr.; Luis; Mary Ann; Aurelio; Pedro, George; Cynthia; Steve; Rolando and Roxanne.

Castillo escaped injury on the battlefield but lost most of his hearing. He recalled waking up one day in a tent outside of Paris with insects all over his body, including in his ears, and thinks that was the cause, although doctors told him they did not find anything in his ears.

He is deaf in his right ear and has only about 50 percent hearing in the other.

“I hear you talking, but I can’t distinguish what you're saying,” Castillo said.

Castillo received the American Campaign Medal, the European African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, with five Bronze Stars, the World War II Victory Medal and a Good Conduct Medal. He is modest about his brave service.

“I was just there like everyone else. Doing my share. I’m just telling the truth,” he said. “I’m no hero.”

Castillo died on June 23, 2015. He was survived by his wife, his children, 31 grandchildren, 35 great-grandchildren and four great-great-grandchildren.

Castillo was interviewed by his grandson, Marcos Castillo, in Robstown, Texas, on Nov. 23, 2012.