By Raquel C. Garza

On June 6, 1944, Lillian Marguerite Ramirez was baking gingerbread men as a surprise for a neighbor's child.

Ramirez's husband, Oswaldo, meanwhile, was thousands of miles away, serving on the front lines on Omaha Beach.

Her brother-in-law, Rafael Ramirez, had come to visit her in her parents’ home in Biloxi, Miss., a day earlier. He arrived the night before D-Day, or Operation Overlord, was scheduled to take place.

"All that day, they kept turning off the radio when I would walk in," Ramirez said.

She said she thought it was strange but she didn't really think too much about it. When she arrived at neighbor Grace Holcomb's house to bring the cookies, Grace greeted her at the door with a shocking question.

"Grace said, 'Well, what do you think about the invasion in Europe?' and I just handed her the cookies and went running back home, and then I realized why they kept turning off the [radio]," Ramirez said. "It turned out that my husband's outfit, the 16th Infantry of the 1st Infantry Division, had hit Easy Red, Omaha Beach, at H hour and the radio had been telling that, and they didn't want me to be upset."

The purpose of Operation Overlord was to open a second front on which to fight German forces. The amphibious attack was scheduled for 6:30 a.m. June 6, 1944. The battle was fought on five beaches: The British fought on the "Gold" and "Sword" beaches, the Canadians attacked "Juno" and the Americans took the "Omaha" and "Utah" beaches.

The battle on Omaha Beach has been described as one of the most difficult of the five. The next day, Ramirez heard her husband's name as she listened to reports on the radio.

"He was alive, and he had been on the beach, and he had rescued some of the wounded out of the water. I suppose he had been nearby where the correspondent had been talking. That's how I knew he was alive, I heard it on the radio after D-Day," Ramirez said.

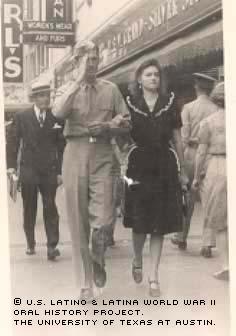

Ramirez first met her husband in the lobby of the Buena Vista Hotel in Biloxi in June of 1940, where the Pan-American Student Forum National Convention was being held. She was president of the Biloxi High School chapter of the forum; she was also state president, representing Mississippi.

"Dr. Sparkman (the sponsor for the Pan-American Student Forum for the state of Mississippi and head of the language department at Belhaven College in Jackson) introduced us and said, 'And she's the state president of the Pan-American Student Forum,' and my husband looked down and said, 'You can't be, you're just a baby,' and I was infuriated!" Ramirez said.

Although she hadn’t been permitted to wear makeup before, that evening she persuaded her mother to let her wear the palest of pink lipsticks and to sweep her hair, decorated with gardenias, up and behind her ears.

After the couple announced their engagement in January of 1943, the sponsor of the forum in Biloxi told her everyone in town had known they were falling in love that night because of the way they looked at one another as they waltzed across the ballroom floor.

The cordial correspondence the pair maintained after to the Pan-American Student Forum had grown into a more romantic endeavor.

Oswaldo asked for Ramirez’s hand in December of 1942, after 2 1/2 years of letter writing and only seven face-to-face visits, which usually only lasted one to four days. The couple's engagement was announced in January of 1943 and they were married in her parents' home in March of 1943.

Lillian said she was the one who decided on a short engagement, because she wanted her husband to feel he needed to fight hard to come back to her.

Ramirez was born July 12, 1922, in Bessemer, Ala., to Grover and Lillian Hollingsworth. She and her family spent many years moving around the United States, as her father was employed with various steel companies and later with the Civil Aeronautics Administration, which later became a part of the Federal Aviation Administration.

While Ramirez describes herself as having grown up a WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant), she said she knew of no difference between herself and members of other ethnic groups.

"Many of my friends had Spanish names, but there was never any mention that they were any different from myself because their families were white ... or intermarried with Anglo-Saxons from the time the Spanish and the French settled the Gulf [of Mexico]," Ramirez said.

She also said there were many prominent families with Spanish and French names, including the Lopez family, for whom the grammar school she attended in Biloxi was named.

Ramirez gave birth to her first child, John Richard Ramirez, on April 4, 1944.

Like most people during the war, she made do with what she had. Clothing, like most other items, was rationed. Her sister-in-laws had to travel to Mexico to obtain some fine cotton material to make clothes for the new baby.

"After the war, when my husband came home, I discovered why you couldn't get the fine baby batiste," she said, referring to a type of cloth. "He came home with a map on the fine cotton and that's what the officers and I think all the troops had ... because if they got lost, they had the map; and it was on the material, so if it got wet, it didn't make any difference, and I thought, 'What a wonderful thing.’”

In November of 1944, she went with her child to Mission, Texas, to visit her husband's family for the Thanksgiving holidays.

"Everybody thinks it's very different to go from the Mississippi Gulf Coast to the Valley," said Ramirez, referring to the Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas. "In truth, the Southern culture is very similar to the Latin culture."

While Ramirez never got to meet her husband's parents, as they died before she met Oswalso, she was able to meet his brothers and sister.

"We got along like a house afire," she said with a smile.

Even though she had only planned to stay for the Thanksgiving holidays, she stayed until May visiting with friends and family members.

"I just seemed to fit right in, and I loved it," Ramirez said. "I think that my husband's family loved me just as much as I loved them."

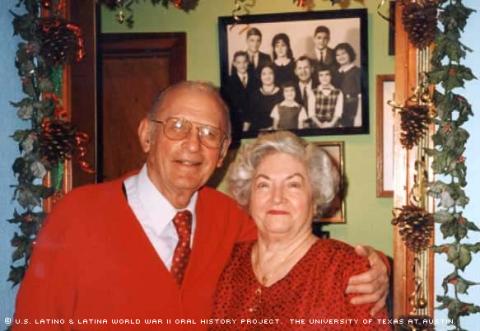

After Oswaldo was discharged from the Army in 1946, they settled in New Orleans, where Oswaldo worked for the Department of Veterans Affairs while going to law school at Loyola University. Their family grew to include six more children: Catherine, Paul, James, Mary, Barbara and Margaret.

Oswaldo worked as a lawyer in labor management for multinational corporations; it was a profession that would take their family to Cuba during the time of Castro's insurrection, and later to many Latin American countries, including Panama, Peru and Honduras. Ramirez said no matter where her husband's job took her and their family, she was willing and happy to go.

"I enjoyed it. Wherever we went, I made a home," she said. "We learned the culture, we learned to eat a lot of the food the people ate."

While reflecting on the past, Ramirez's thoughts went to the present, giving future generations words she hoped they would live by.

"Do what you have to do. Do it willingly, don't complain, but try to just go on with you life," she said. "Don't put your plans on hold ... just try to keep on track, because in the end it will all work out all right. You'll have twists and turns in your life that you never dreamed would happen."

Mrs. Ramirez was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on October 8, 2001, by Raquel C. Garza.