Lorenzo Banegas was one of more than 1,700 New Mexico National Guard soldiers taken prisoner on Bataan.

No state paid a higher price - more than 900 New Mexico captives died. Banegas survived, but even today - 72 years old and retired in Las Cruces - he agonizes over the terrible memories.

He survived the brutal Bataan Death March, where thousands of soldiers died of disease, torture and starvation. By 1943, he was a prisoner at Cabanatuan in the Philippines, suffering from diphtheria and beriberi.

"I was so tired. I was so darn tired that I said I don't care if I live or die."

Adolfo Rivera, a friend from his New Mexico National Guard unit, intervened. "If it wouldn't have been for him, I wouldn't be here right now," Banegas said.

"He picked me up. He said, 'No, Banegas! Come on, let's go out and put some water on you.' He took me up there and threw some water on me. I said, "Ooh, gosh, I feel a lot better now."

"And then when he saw that I looked up again, he said, 'Come on, let's sing us a song!' And he started singing this song:

"Cuando se quiere deveras, como te quiero yo a tí." (When one loves truly, the way that I love you)

It was a love ballad both had sung as boys in New Mexico.

"Golly, every time I hear that song," Banegas said. He burst into tears.

Rivera died in Japanese captivity.

"I'd give my life for his right now if I could," Banegas said, sobbing.

About 12,000 Americans and 55,000 Filipinos became captives of the Japanese April 9, 1942, including more than 1,700 members of his 200th Coast Artillery (Anti-aircraft) Regiment from New Mexico National Guard and the 515th Coast Artillery Regiment (AA) formed in the Philippines from one of the battalions of the 200th and other local troops.

When the island fortress of Corrregidor fell a month later, another 11,000 Americans were taken prisoner. More than half the 23,000 U.S. prisoners of war died in Japanese captivity - of disease, starvation, torture and execution.

Successive generations of Americans have had their wars in Korea, Vietnam and the Persian Gulf.

And during that time, the number of New Mexico survivors of Bataan still alive fell to fewer than 300. Each day they have left will be mixed with pain and pride.

On December 8, 1941, 10 hours after Japanese warplanes wiped out much of the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, another group of bombers unleashed their fury on the Philippines.

The islands then were a U.S. territory, and military leaders considered them a key to the defense of the Pacific. But the forces there were woefully equipped for the task.

Most of the 110,000 allied soldiers on the island were poorly trained Filipino conscripts, and many of them melted into the hills when the first shot was fired. Those who fought used World War I-era equipment.

The Japanese threw 190,000 soldiers, sailors and airmen at the Philippines, and many of them were hardened combat veterans.

The emperor's military leaders considered the Philippines an easy conquest. Their timetable called for the islands to be overrun by the beginning of 1942.

But the U.S. and Filipino forces put up an unexpectedly stiff resistance. The allied forces executed a masterful strategic withdrawal into the Bataan Peninsula - a strip 30 miles long and 20 miles wide that was dotted with lush jungle and volcanic mountains. They fought the better-equipped Japanese to a stalemate for several months. Although U.S. officials repeatedly promised reinforcements and relief, none came.

By early 1942, the Allied troops were running out of food and ammunition. Tens of thousands of soldiers suffered from malaria and other diseases.

The choices: Surrender or face wholesale annihilation. Maj. Gen. Edward King, commander of forces on Bataan, decided to surrender April 8, 1942, effective April 9th.

Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainright, faced with a similar dilemma on nearby Corregidor, chose to surrender in early May.

April 9, the Japanese victors began marching their 67,000 prisoners from Mariveles on the southern tip of Bataan to Camp O'Donnell in the interior of Luzon.

The captives, many already deathly ill and malnourished were forced to make the 90-mile journey with virtually no food or water. Most of the march was on foot along a blacktop road where temperatures soared to 130 degrees. The rest of the trip was made in suffocating railroad boxcars.

It was the Bataan Death March.

Any prisoner too weak to continue was shot or bayoneted by Japanese guards.

An estimated 7,000 to 10,000 prisoners died on the march. About 90 percent were Filipinos.

At Camp O'Donnell, the captives died by the hundreds every day. There was no medicine to cure their illnesses, almost no food to silence their growling stomachs, precious water to quench their parched throats.

Lorenzo Banegas had the job of burying the men who died in his section of the camp.

"Every morning we had to go out and pick up the fellows who died that night. We picked up 20 to 80 every day," Banegas said. He was a member of the 200th Coast Artillery.

The dead were buried in shallow mass graves outside the camp.

In June 1942, the Japanese began releasing most of the surviving Filipino captives. The U.S. prisoners were sent from O'Donnell to work as slave laborers in other prisons in the Philippines - with names like Cabanatuan, Davao and Bilibid. Others were sent to Japan to work in coalmines and shipyards. And they kept dying.

Many captives found it easier to die than live.

"There was a lot of them that died because they didn't want to live anymore," Banegas said.

He remembers one of his boyhood friends, Lorenzo Herrera, who lost his will to live in Cabanatuan. Herrera had constant bouts of malaria and grew tired of suffering. Banegas would force water and food down his throat to keep him alive.

"He told me, 'You know what, tocayo? I would appreciate it more if you let me rest. I want to rest, and don't let me rest.'

"The next time that he had another attack of malaria, he just stayed there because he told me not to bother him. And he just died there like he had gone to sleep. He just lay there resting, like he said."

The last of the U.S. prisoners were freed August 1945, after the Japanese surrendered.

Of the 23,000 U.S. soldiers captured in 1942, only about 11,000 were still alive.

(This article was first printed in the El Paso Times on April 5, 1992. The interview with Mr. Banegas was tape-recorded and has been donated by reporter/editor Robert Moore for use in the U.S. Latino & Latina WWII Oral History Project. The project has secured the written permission of Mr. Moore and Mr. Banegas to include the interview and a transcript of it in the archives.)

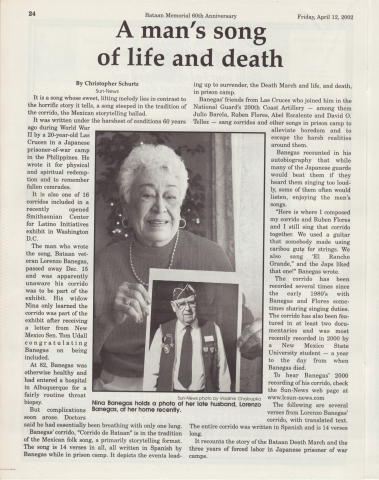

Mr. Banegas passed away on Dec. 15, 2001 in Las Cruces, NM.