By Hason Halpert

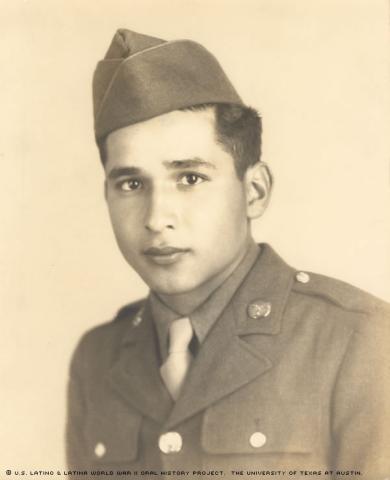

For Air Force Gunner Luis Garza, the worst thing that could have happened to him during World War II occurred before he even got overseas.

“While we were waiting [to go overseas], my mother got a notice that my brother [Pablo Garza] had been killed [in France],” Garza said. “I was playing ping pong, and my mom called and said my brother was missing. He was reported killed in action later that day.”

Rife with emotion, Garza asked for a leave of absence from his port of embarkation in Georgia.

“I went home for five or six days,” he said. “The toughest part was that my brother had a son right after he died. He died in December and his son was born in January. His wife was in the hospital and didn’t even know he had died yet.”

Pablo’s passing made sleep difficult for Garza during those six days; however, this wasn’t his first bout with insomnia.

When Garza was a child living in San Antonio, Texas, he had trouble sleeping, so he’d always be up in time to help his father get produce for their grocery store. Once older and still a bad sleeper, he enjoyed mixing dough for the bread at their bakery before he went to school. Then December 7, 1941, rolled around and Garza was left in shock, facing new and uncertain times and hoping he’d be allowed to continue with his family traditions, rather than fight the Axis Powers overseas.

Talks between Japan and America gave no hint of the devastation about to come. While Americans were letting their President know they didn’t want to get involved in the war, Japan was planning a surprise attack that proved fatal to itself in the end. By the time President Roosevelt gave his now famous speech in December of 1941, about a moment that will live in infamy, many able-bodied young men were enlisting to defend their country. Garza wasn’t one of them yet, however.

“At the time I was 16, and I was really hoping the war would be over by the time I was 18,” he said. “I had no interest in volunteering; the Army was the last place I would want anyone to be.”

While Garza didn’t want to join the Army, he and his neighborhood were still proud of the United States for throwing its hat into the war.

“Everyone [in the neighborhood] was out in front of my father’s bakery saying, ‘Oh, now we are going to go show them [the Germans] what we can do’,” Garza said.

Uncle Sam eventually called upon Garza, along with older brother Pablo.

“It was October 16, 1943; we got drafted together,” Garza said. “There were no regrets; it was our duty to serve.”

The brothers had to take a series of tests to decide their placement in the Army.

“We needed a 110 or better for officers training, and both my brother and I got [over] 110,” he said. “Then, originally we needed a 180 to pass the [Air] Cadet Program test. I made a 205 and Pablo made a 189. Then they changed the scoring and you needed a 190 to go on, so Pablo got sent to [the] infantry …”

As it turned out, the Army officer schools were closed, so Garza’s only option to become an officer was the Air Force. He was OK with that, and went to Shepherd’s Fields in California for more tests, where he recalls finding some lingering discrimination.

“Out of about 60 of us, I’d say maybe 20 of us passed the tests, and everyone there would be saying, ‘How did that Mexican pass the test?’” he said.

While at Shepherd’s Fields, blacks and whites were segregated, Garza recalls.

“On Sundays our mess hall was closed, but the Blacks’ hall was open, so we would go eat over there. … That was OK with us, because they usually had better cooks anyway!” said Garza, to whom segregation didn’t seem out of place.

“I was raised that way,” he said. “We went to different schools and everything. Of course, I had no ill feelings towards them. Most blacks bought at my dad’s store so I knew them well. I even played baseball with some of them.”

After a little training, the government decided it had too many cadets, and eliminated all of the new ones, Garza says.

“We were given an option of going to radio school, mechanic school, gunnery school or the armory school,” he said. “I chose radio school because I had some radio training.”

This option also failed Garza, as all of the radio schools had been filled up, he recalls.

“The government had to do something with the people that had chosen to go to radio school, so they sent us to Arizona for gunnery school, where I became a ball-[turret] gunner.”

After schooling, Garza was sent to Mississippi for crew training, where he finally met the crew he’d work with until after the war, part of the 8th Air Force’s 527th bomber squadron of the 379th bomber group. When the training was done, they all went together to Georgia to meet the plane that would fly them overseas. While they were waiting, however, disaster struck: Garza was informed of Pablo’s death.

“It was really sad. We wrote each other every day,” he said. “In fact, I still have the letter my brother sent me, the last letter that he ever wrote to me.”

After spending some time grieving with his family, Garza flew out to England to meet with his crew.

“I ended up in Kimbolton,” he said. “We were in training over there for about two more weeks, so that the pilot could get familiar with the flying patterns of the bombing crew.”

On a few of their bombing missions, Garza and his crew were hit pretty hard by flack.

“When we got hit, we often landed in Brussels,” he said. “We [descended] too fast, so I always got a cold.

Ear problems became such a problem for Garza he says they almost derailed his stint in the Air Force.

“I got a real bad cold every time I flew,” Garza said. “My ears would get stopped up real bad, so much so that I ended up in the hospital for three days one time. I was even given the option to stop flying because of my ears, but I just kept going.”

With Garza’s first set, he and his crew flew five consecutive missions. With four days off before the next five missions, however, they had a lot of free time to spend overseas. They visited many cities in England and Belgium, wrote Garza after his interview.

“They gave us a pass to go anywhere we wanted to on the trains,” he said. “Of course you have to find a place to stay as well, but the people are nice over there.”

Garza didn’t meet many Mexicans Americans in the Air Force; however, in London he ran into a lot of them.

“The infantry in Europe often sent Mexicans on rest and recuperation in London, so I would often just hang around with those Mexican people” from other states, he said.

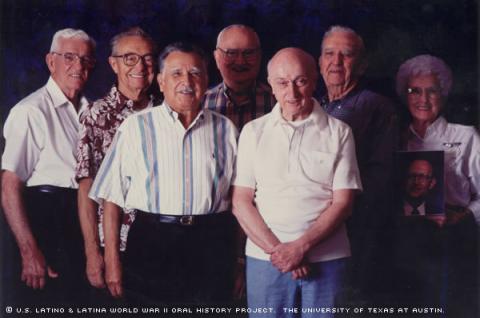

Although Garza liked keeping ties with the Latinos he met overseas, he became entrenched with his new family: his crew. Even to this day, he can recite where everyone was from.

“The crew I was in was a very good, friendly crew, very friendly,” he said. “The pilot was from Alabama; the copilot, California; The navigator, Texas; the waist gunner, Arkansas; the nose gunner, Pennsylvania; the radio operator, Florida; the tail gunner, Texas. We all got along real well.”

By April of 1945, his tour was over. Although the war officially ended in May, however, Garza had a little trouble getting out of the Army and going back home.

“By the time I decided to get a pass, they wouldn’t let us out,” he said. “In fact, they made us guards to keep people from going out” to celebrate.

After VE Day, the Army Air Forces gave a 30-day furlough for the soldiers to go home. Garza arrived in the States on July 4, 1945.

“It was a good day,” he said. “The Red Cross gave us bottles of milk, and I hadn’t had fresh milk in a long time. So I drank too much fresh milk and got sick.”

Garza says he was supposed to regroup in Iowa on August 14 to get ready to go to Japan.

“They were going to retrain some of the people,” he said. “But if you had over 110 hours of combat flying time, you didn’t have to go.”

By Jan. 5, 1946, Garza was finally out of the service, enabling him to go to college and move on with his life. He earned a degree in Mechanical Engineering from Texas A&M, although he wasn’t too fond of the school.

“A&M is what I would call a chicken school – they try to fail you,” he said. If you don’t study, you won’t make it. If they could fail you, they would. That made my first year a little hard, ’til I got into the system of studying more.

Today, Garza is officially retired, living in San Antonio with his wife, Olga. He has new traditions and a new way of life, not to mention three kids who all went to college.

Looking back at his time in the Army, he expresses no regrets, despite not liking it.

“A lot of people like the Army. I don’t. It’s a place for people without direction and ambition. That’s only my opinion,” he said. “If anyone was to serve, the Air Force is probably the best place to serve. They treat you well and you eat well there.”

Garza says his only regret about the war as a whole is that it cost his older brother his life.

“In the end, it was our duty to serve, so we did,” Garza said. “The saddest thing of all was losing my brother. … My brother died without even knowing he had been promoted. He never had time to enjoy life. He worked right when he got out of high school, married, went into the service and died in the service.”

Mr Garza was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on May 5, 2007, by Raquel C. Garza.