By Shelby Custer

In December of 1975, Guadalupe Arredondo Uresti, a 31-year-old homemaker, spoke at a kick-off rally for the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project in the old Civic Center of Rosenberg, southwest of Houston.

Uresti, who also devoted time to working in her father's furniture business, remembered exhorting her Mexican American neighbors to register and to vote - to make their voices and needs heard. Even though she trembled with nervousness, she made an impression.

"At the rally, [local attorney] Paul Cedillo came to me, personally, and said, 'Lupe, you should think about running for [city] council.' I remember thinking, 'There's no way I would consider that,' " she recalled. "But, it always takes someone to put it in your mind."

Cedillo's comment inspired Uresti to run for office. She won a position on the Rosenberg City Council. Later, in 1992, she was elected mayor of Rosenberg. Her political trajectory parallels the rise of Mexican-American political power in her city.

It had come a long way from 1975, when U.S. Rep. Barbara Jordan (D-Texas) heard their complaints of being turned away at the polls. (Jordan sponsored legislation that year that extended the 1965 Voting Rights Act and broadened it to cover Latinos, Asian-Americans and Native Americans.)

Once Latinos became more politically aware and active, the election of a Mexican-American woman in Rosenberg to the city's highest elected position became a possibility.

"After I was elected, older ladies would come to me and cry because ... it was a reality that they thought they were never going to see," Uresti said. "My election was a door opener for all Hispanics."

Uresti and other Mexican-Americans in Rosenberg had suffered discrimination, segregation and inequality in politics and in their day-to-day lives. But Uresti's efforts helped to create a pathway to equal rights for minorities.

She was born Guadalupe Arredondo on April 21, 1944, the second of six children of John Arredondo and Nicolasa Becerra Arredondo. The Arredondos owned a thriving furniture store in the minority area north of the segregated town's railroad tracks. At that time, Whites lived south of the tracks in Rosenberg, which had about 9,000 residents.

"Anglo customers would come and buy furniture and ask for it to be delivered after dark," Uresti said. "They didn't want other people to know where they bought the furniture."

A soda fountain at the Pickard & Huggins drugstore sold ice cream to Mexican-Americans, but they weren't allowed to sit down at the counter to enjoy it. Similarly, the Cole Theatre separated races by levels; non-Hispanic Whites were on the first level, Hispanics on the second and African-Americans on the third. At the time, Uresti wasn't bothered by watching movies at a segregated venue; it was just the way things were.

Although schools in Rosenberg allowed Mexican-Americans and Whites to attend together, African-American students were schooled separately. Full integration didn't occur until 1964, a full decade after the United States Supreme Court ruled that public school segregation was unconstitutional.

By the time Uresti graduated from high school in 1963, it was common for Mexican-Americans to receive a high school diploma. However, very few continued their education at a college or university.

"We had no encouragement from school, or anything, to continue our education," Uresti said.

There were also few role models.

"There were no Hispanic doctors or attorneys and very few business people in Rosenberg," she said. "So, we had no aspirations."

But the Arredondo children, with strong encouragement from their parents, pursued higher educations. She and four of her siblings attended college; she was the only one to earn an associate's degree.

Guadalupe Arredondo married Gilbert Uresti on July 4, 1965, and the couple had two children. She became active in her community and involved in the Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church. She was appointed secretary of the church's Parish Council and extended her network of contacts.

In the mid-1970s, Uresti's activities became more political. In 1974 (nine years after the Voting Rights Act was enacted to eliminate barriers to voting, specifically for Blacks), several Mexican-Americans lined-up to vote for Cedillo, a Mexican-American candidate in a local school board election. But many complained that they were not allowed to vote and that they had been told they needed other documentation, or were turned away for other reasons. Subsequently, individuals sent affidavits to Congresswoman Jordan, who was the first Black woman from the Deep South to be elected to Congress.

A local teacher, Dora Olivo, became active with the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, which had been created in 1974 in San Antonio by Willie Velasquez. Uresti and others in the community joined the Project.

They went door to door, encouraging Hispanics to register and to vote.

"I had never been involved in any sort of political action before," Uresti recalled.

The turning point was the kick-off rally in 1975.

She lost her first bid for office in 1976. Three years later, Uresti began her first term at the age of 34 on the Rosenberg City Council. She served for several years and later became the mayor. But, as a Mexican-American woman, trials also accompanied her victories.

She recalled her failed 1976 electoral effort. "To this day, that election had the largest voter turnout in the history of Rosenberg. They all came out to vote against us [Mexican-Americans]," she recalled. "The Anglos did not want Hispanics on the council."

When Uresti was elected as mayor, she found there was no office for her to work out of, even though previous mayors had offices. City council members also had no offices. Uresti set up a chair and table in a hallway to conduct her daily duties. Eventually, she was allowed to work out of the council chamber room, which she shared with members of the city council.

"They told me I didn't need an office," Uresti said.

The integration of City Hall was a process of raising awareness. "You do not know how hard it was for the employees to see a Hispanic woman as mayor," she said.

In 1978, she ran for and was elected to the Rosenberg City Council. While on the council, she also served as: trustee for the Economic Development Council and vice president of the Rosenberg Chamber of Commerce.

Uresti said that she also sought to use her position to empower the Mexican-American community.

"What I wanted to do was to be their [Mexican Americans'] voice for what they thought was lacking in representation. Whatever their concerns, I was their voice," she said. "I wanted to make them feel empowerment in the city."

As mayor, she voted for the implementation of a federal public housing program. It was an unpopular stance, but she thought it was best for all demographics within the community. There were protests, where people carried signs saying, "Not in My Backyard." Ultimately, that vote caused her to lose her bid for re-election to a third term as mayor, she said.

Through her efforts on the city council, as mayor and with the voter rights project, Uresti promoted equality and provided encouragement for the Mexican- American community of Rosenberg. Now, Uresti said, "The doors are open everywhere."

On the other hand, according to Uresti, further action is required.

"More Hispanics are coming out to vote, but there's still a lot lacking in motivating and goals for the community," she said. "The key to keeping the community moving in the right direction is education."

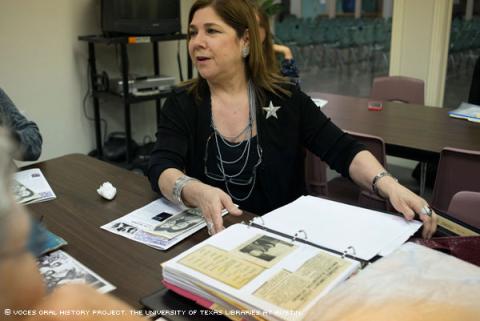

Ms. Uresti was interviewed by Shelby Custer in Richmond, Texas, on March 23, 2014.