By Guillermo X. García

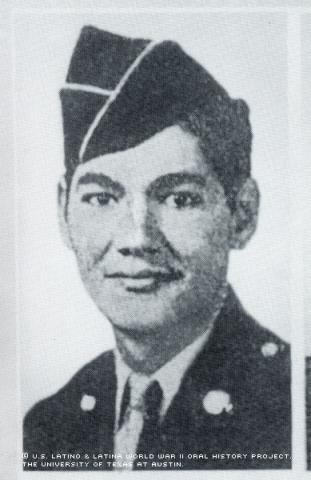

Manuel C. Vara was a high school senior attending a Sunday movie matinee in his hometown of San Antonio when news broke out on the screen: All soldiers were to report back to base immediately. Japan had launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor that morning in December, and the United States' entry into the war was imminent.

"Right then, I had no idea where it was, or what was about to happen, but when I got home, my brothers were all talking about it, so I knew something important was happening," he recalled.

The second-youngest of an eight-child family, the 17-year-old could hardly contain himself. One month after the "day that will live in infamy," as President Franklin D. Roosevelt called it, Vara turned 18, old enough to join the military.

During his three years attending Fox Tech High School, he’d been a member of the ROTC, "so it was a really big thrill to sign up" for the "real" Army experience, said Vara, who’d leave for war before finishing high school. He also knew he’d have to leave behind his trademark suspenders: "I wore them because my heroes, George Raft and Cagney, wore them all the time," he recalled.

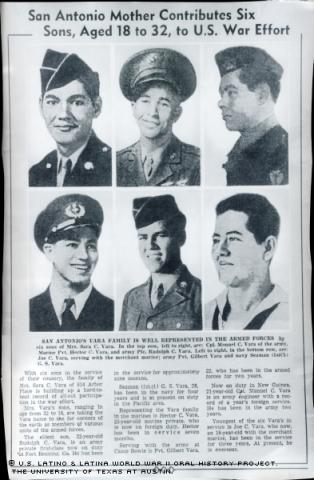

Vara volunteered for what he considered a lark and an adventure and was inducted. Before the war ended, all six Vara boys, ages 16 to 32, were to go off to war. Manuel and an older brother served in the Pacific; the rest were sent to the European Theater. All six would return home safely.

"We all thought it would be a great adventure, but we learned different. [War] takes a lot out of you as an individual, but at the same time it makes you wiser to the realities of life," Vara said.

The mood among young Latinos in Vara's neighborhood was one of excitement and elation. It was a deeply patriotic mood that especially infused the young men. A number of good buddies decided they’d join up together.

"I was eager to get in to the war. I may not have understood it, but I saw it as someone attacking our country, and our response was that the proper thing to do was to fight back. We understood that [joining the military] was the patriotic thing to do, and for me at least, it was not a question of trying to get revenge against Japan, but simply that they needed to be stopped or else who knows where it would end if [Japan] was not stopped on their side of the Pacific," Vara said.

"The advice my parents gave me was to do a good job, and they gave me their blessing," he said.

They’d do the same to his five brothers, who’d all go their separate ways to fight: Jose, the youngest, and the only one to graduate from college after the war, was in the Air Force and the Merchant Marines; older brother Hector joined the Marines and saw action at Iwo Jima; Rodolfo, known as Rudy, served with Gen. George S. Patton's Tank Corps in North Africa; Gilbert was an Army Medical Corpsman in Europe; and Salvador served in the Navy aboard the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga.

Although Vara's Army unit, the 340th Engineer General Service Regiment, later the 340th Engineer Combat Battalion, was involved in a number of Pacific battles, like the attack and capture of a number of islands in New Guinea as well as the liberation of the Philippines, he was never involved in direct, front line combat. However, his effort as Tech Sergeant and the efforts of his fellow engineers were critical. They built airfields, bridges and roads so military material and support could flow to the front lines. Vara's engineering skills were so valuable at basic training in Louisiana that he almost didn't ship out with the rest of his unit.

"They wanted me to stay and be a trainer, but I was young and what I wanted was to go to war, to fight," he said.

From Louisiana, Vara moved by train to North Carolina, where he joined the 340th unit, then to New York state and, later, Portland, Ore. From there, the 340th boarded a ship sailing to Australia. It took almost 45 days, Vara recalls, as the ship zigzagged through their route to avoid prowling submarines.

Vara clearly recalls some of the battles he witnessed, including the bloody assaults on the New Guinea beaches of Biak and Hollandia. After two years of duty in the Pacific that culminated with the successful U.S. invasion of the Philippines on Jan. 9, 1945, he was stationed at Clark Field near Manila. There, he met and befriended aviators from the famed Escuadron 201, the Mexican fighter squadron that saw extensive action in the Pacific. It was while he was with the Mexican pilots that he learned the war was finally over.

"There was a party going on everywhere, and anywhere you went, you could not pay for food, for beer, for anything, because the natives were refusing to take money, they wanted to treat," he said.

While he doesn’t remember exact details, he does recall eating lots of one of his favorites, arroz con pollo, or chicken and rice, during his end-of-war festivities.

"It sure beat eating potatoes," which was a staple of Army life, he said. But even after the atomic bombs were dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Vara wasn’t able to return home. Because he was single and had no dependents, he was selected to serve as part of the post-war occupation force in Japan, as the devastated nation transitioned from war-wager to vanquished foe.

"I was nervous and probably scared. I didn't have any idea what we would be coming across," once the U.S. ships landed in Japan, he said.

He was pleasantly surprised, however, that upon reaching Nagoya, he wouldn’t encounter any hostility.

"The Japanese just were glad it was over, I guess." Vara said, and judging by the devastation he saw, he understood why. "Nagoya must have been a manufacturing town, [and it] had been destroyed. I mean it was nothing but ruins."

Vara said he returned to the U.S. a wiser, more mature man, aware of the sea of changes that were to involve Latinos.

"Prior to [shipping out], I didn't know what I was capable of achieving, of what it is that we wanted to get out of life. When we came back, we, the Mexicans, had much more confidence in ourselves and we realized that we deserved to get a better education [than was available], just to see how far we could go."

Upon his return, he attended college at St. Mary's University, but didn’t graduate; however, his war experience made him realize Hispanics would no longer easily submit to the segregation they’d faced before the war.

"Before the war, promotions for Mexicans were few and far between. But after the war, I would insist on being considered for promotions, and if I knew I was qualified but didn't get the job, I would not let that stop me. I would try again next time for a promotion."

As an example, he cites an incident that occurred shortly after his Army discharge, when he went to work for the Postal Service, where he eventually became a postmaster.

"I was refused the opportunity for promotion once. The reason they said was that the public was not ready to have a Mexican selling stamps at the [post office] window. I kept after it until I got the job. That tells me that it is only a difficulty if you make it so," Vara said.

Mr. Vara was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on November 15, 2001, by Martha Treviño.