By Lena Price

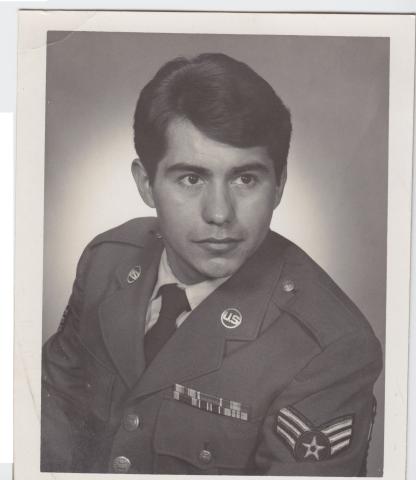

It was an evening like any other in Saigon in April 1968, Manuel Cavada, an Air Force crew chief, was doing the routine maintenance on C-121’s aircraft. His job was to make sure the engines were free of metal debris.

But within minutes, he realized that rockets had been fired and were heading his way.He did not expect to get caught in the middle of an air raid and come close to death.

Cavada said he tried to outrun the barrage of rockets by sprinting along with other men to a nearby bunker. One of the marines guarding the planes threatened to shoot them if they didn’t go back.

He told the marine he couldn’t stop and cussed him out.

“Three days later the marine found us and said, ‘If you hadn’t cussed at us, you’d be dead,’“ Cavada said.

But as they were running to the bunker, Cavada felt an intense pain in his right leg.

“A big chunk of metal was in it. . . it was still sizzling when I pulled it out,” he said.

At the same time he saw his friend, Frank Macias, lying on the ground. Cavada called out to him and he did not respond, so he crawled over to his friend. When he got there, he saw a Frank lying on his stomach, a gaping wound in his back.

“I dislodged a huge piece of metal in his back, and he started shooting blood all over the place,” Cavada said. Cavada took what was handy – his white socks -- and “popped” them into the gaping hole in Frank’s back.

When a Viet Cong came to survey the damage, Cavada held Frank’s mouth shut, trying to keep him from screaming. The Viet Cong left and later the Americans came to clean up and take the wounded to the hospital.

Cavada said Frank’s mother later thanked him.

She told him: “you’re the man who saved my son’s life. And I said, ‘No ma’am, we saved each other.’ But she was crying and hugging me,” Cavada said.

The attack on Tan Son Nhut Air Base left several people dead.

Cavada said he was able to make contact with Frank after the war.

Cavada, an airman first class, later earned a commendation for spotting a broken airplane part that would have likely led to a crash. But Cavada said he never considered himself a hero, and the near-death experiences did not change his perception of life. He did, however, think about the incident every day.

“It didn’t change my life philosophy or make me happy to be alive,” he said. “I was happy to be alive before that.”

Ever since he was a child growing up on the west side of National City, Calif., Cavada said he was optimistic. He was one of eight children – four brothers and three sisters. His oldest sister, Estella, helped take care of all the kids because Cavada’s parents were often working.

He recalled family traditions, such as Halloween, when the family’s kids would stuff bag after bag with food, candies and apples. At Christmas times, the extended family gathered in one home, sometimes 60 kids were there.

Cavada’s mother, Eloisa Osuna, was born in Albuquerque, N.M., received a middle school education. She worked for 35 years as a fish cleaner at Sun Harbor, a cannery.

“On her day of retirement, her gift was a case of tuna! After 35 years, it was the last thing she wanted to see. . . but she loved it anyway,” Cavada said.

His father, Manuel Cavada, immigrated illegally from Monterrey, Mexico and found a job as a painter for National Steel Corp., a major steel producer.

Cavada said he had different opportunities from his parents. He never had to struggle to learn English, because his parents never taught him any other language. His father insisted that he needed to speak English fluently if he wanted to find a job in the United States, , although Cavada is learned Spanish as an adult.

Because of his English proficiency and personal drive, Cavada said he was able to graduate from high school and he wanted to pursue a college education. After high school, he spent two years working at an auto body shop before joining the Air Force.

After his time in the service, Cavada obtained an art degree from the Glen Fishback School of Photography in 1974. He still worked as a photographer at the time of his interview. One of his counselors, however, had told him he would be better off pursuing a career as a mechanic.

But even as a teenager, Cavada knew he had no desire to be a mechanic. He said he knew he wanted to be a leader from an early age.

Although he was “blessed with two lovely parents,” Cavada admitted that his father regularly beat his sisters. In 1955, when Cavada was 11-years-old, he sat down with his father and sister and said “don’t hit her anymore, hit me.”

“I had a drive to be somebody that knew how to manage people and communicate,” Cavada said.

His need to learn more about himself and to get a good education was one of the main reasons why he enlisted in the Air Force in 1964, two years after he graduated from high school.

He went to basic training at the Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, and most of his friends from his California community had already enlisted.

Cavada’s feelings toward the war did not change from the beginning to the end of it. When he enlisted, he said the entire conflict was based on a “giant lie” by the government. He did not feel any animosity toward the Vietnamese, and instead said he could relate to many of them.

“I always thought the Vietnamese were a lot like Mexicans,” Cavada said. “They were honorable families and they worked hard. We were brainwashed to fight an enemy. We were told to fight communists, but I had to ask my Sergeant, ‘What is a communist?’”

Cavada said he felt the same kind of connection with the Vietnamese that he felt with all of the other soldiers serving in his unit. He said that no one paid attention to the color anyone’s skin in a war environment.

“I didn’t feel like I was going to war, I didn’t want to hurt anybody,” Cavada said. “Our war was to stay alive for one extra day. Our war effort was within ourselves.”

(Mr. Cavada was interviewed on June 6, 2010 in National City, Calif., by Olivia Puentes-Reynolds.)