By Angela Macias

Manuel Aguirre’s small stature prevented him from joining the Marines, but it didn’t keep him from doing his part in the war effort.

After hearing President Franklin D. Roosevelt tell the nation the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor, Aguirre knew he had to get into the service somehow.

"What's going to happen now, I wonder," said Aguirre of his thoughts after hearing the news on the radio. "I thought if I had to go, I'd go."

He ended up finding a place in the Navy, learning first how to be a part of an "Argus Unit,'' studying radars. Those types of units were abandoned before his time to head into war, however, so officials sent him to special amphibious training in Coronado, Calif. at the Lading Craft Control School.

In spite of his inability to swim, Aguirre found a place as a coxswain. The physical characteristic that kept him out of the Marines was an advantage in the Navy, as his position was earned because of his height.

"They lined us up according to height," Aguirre said. "All the guys on the frontline ... [they said,] you are all going to run the boat."

Aguirre explained in a letter to the Project after his interview that "being short, your head didn't stick up high going into the beach in landings and invasions."

Practicing for two months and able to maintain his boat the entire time, the Minnesota resident finally left the U.S. mainland for Pearl Harbor in December of 1944.

Aboard the U.S.S. Ozark, part of the Navy Special Amphibious Forces, the seaman first class toured the South Pacific for 12 months -- from Sept. 28, 1944, until Oct. 12, 1945. Their first stop at Pearl Harbor was brief. And not long after that, Aguirre found himself, along with the Ozark crew, rescuing 800 sailors in the Philippine Islands’ Luzon Lengayen Gulf. The Japanese had sunk the sailors' ships.

The crew set sail before Aguirre's boat had returned, he recalls. So as he saw the landing ship fleeting off in the distance, he and another sailor's boat sped up to catch the vessel, just in the nick of time.

"We just opened that boat up full speed and caught up with them," said Aguirre, who explained in his written comments that suicide Kamikaze planes were coming in and the boats had set sail in order to avoid being "sitting ducks."

Once aboard, the ship returned to Hawaii to drop off the extra soldiers. They bounced around the Pacific islands before setting out for another rescue mission.

As forces tried to secure Iwo Jima, Aguirre found himself rescuing wounded Marines during February of 1945. On the island for a week, the U.S.S. Ozark served as a hospital ship to some 1,000 injured soldiers, he says.

Aguirre also wrote that he took the dead Marines back to the beach to be buried, and the ones that died while the ship was sailing were buried at sea.

Their next stop, after dropping the wounded off at Guam and traveling between the different islands, would be Okinawa, Japan. Aguirre and his fellow seamen reached Okinawa April 1, 1945, witnessing a kamikaze attack from suicide bombers, Aguirre says.

His ship served as a transporter of supplies, going between shore and sea to assist those on land.

After the American invasion of Okinawa, Japanese prisoners of war and wounded Americans were transported on the ship to Guam. The next action Aguirre would see wouldn't be until August of 1945.

A torpedo was shot at his boat on August 16, when they were headed to Japan.

"The captain, he zigzagged our ship and the torpedo missed us," he said.

Though many of the soldiers would need to get away from the boat from time to time to balance out the stress of battle with free time, Aguirre says he would rarely leave. Instead, he filled in for cooks in the kitchen or did odd jobs. He enjoyed staying onboard because he could save money, which he sent back to his mother in St. Paul.

"I didn't get very much money," he said. "So, I didn't care to go ashore too much."

Aguirre recalls in his letter that he spent 3 days free time off-ship in about a year: two one-day liberty passes in Pearl Harbor and New Caledonia and once for a beer party on one of the islands.

With eight siblings back home in the Midwest, his parents, Asención and Aurelia Alcantar Aguirre, both immigrants from Mexico who’d labored for a time as migrant farm workers, looked forward to the money Aguirre sent them every month. In fact, he left school after the sixth grade to help his family out, toiling in the fields until he was 17 years old.

At that time, the war was on and businesses needed help desperately. Aguirre tried his luck at one company, but got turned away because he was too young. He eventually landed a job with Armor and Company, who hired the youngster without checking his birth certificate.

These checks and letters sent to his family would be the last correspondence he’d have with his mother. She died on Dec. 9, 1945, while he was overseas.

Before returning home to his family and friends in the United States, Aguirre and the crew of U.S.S. Ozark ended up in Tokyo Bay from August 27 until the Japanese surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945. Aguirre's ship was the first one to anchor there.

His boat was anchored next to the U.S.S. Missouri during the surrender ceremony, so he was able to see Gen. Douglas Macarthur signing the treaty.

"All the sailors were dressed up in their whites," he said. "We seen the signers from our ship."

Back in the United States, Seaman 1st Class Aguirre got a great homecoming. As his ship pulled in to the San Francisco Bay on October 2, other military vessels greeted them with cheers. The salute was given to them because his ship was bringing in the American soldiers and Canadians who’d previously been prisoners of war, he says.

"When we went underneath the Golden Gate Bridge ... they were all blowing horns and shooting water in the air," he said.

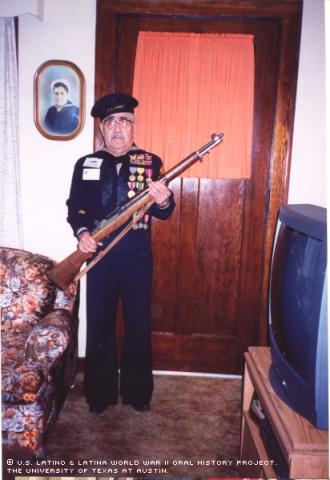

Aguirre remained in the Navy for nearly four more months before being getting discharged on Jan. 19, 1946. He earned many ribbons and medals for fighting in the Asiatic Pacific Campaign and Pacific Area Campaign. He was also issued the Chinese Memorial Ribbon and Medal.

During those months, he experienced segregation for the first time in West Virginia. Growing up in the north, Aguirre didn't attend a segregated school and in the Navy, Blacks slept in separate quarters, but Latinos weren’t segregated. When Aguirre saw the racial division in the south, it confused him.

"I had never seen that in my life, [it] made me feel funny," Aguirre said. "I wondered where I was supposed to go."

Once home in Minnesota, Aguirre soon married Dorothy L. Hansen. The couple had four children: three boys and one girl. Aguirre returned to his job as a butcher in a meatpacking house, working there until the plant closed in 1979.

Though he made it home safely, he says he felt as though one of his family members died in the war -- his mother.

The last time he saw his mother, she was seeing him off at the train station.

"Coming home and she's not there anymore -- it's different," Aguirre said.

Mr. Aguirre was interviewed in St. Paul, Minnesota, on August 12, 2002, by Angela Macias.