By Cheryl Smith Kemp

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, 14-year-old Manuel Juarez was raring to go.

“I had been keeping up with the war in Europe, so I was more or less aware of what was going on,” recalled Juarez more than 60 years later.

His parents, Augustin Juarez, an orange- and lemon-grove laborer, and Belen Sanchez Juarez, a housewife, gave him permission to enlist, but not until he turned 17.

“I insisted on going and they finally gave me my way,” said Juarez, who didn’t have to serve because he was the only son of, at the time, a brood of seven.

A few months later, on Nov. 22, 1944, he was called up for active duty in the Navy.

“I was kind of concerned, because they had just landed in Normandy and the

Philippines was being liberated and I was anxious to get in and actually take part in it. … I wanted to serve my country,” said Juarez, who wound up in the Navy largely thanks to the process of elimination.

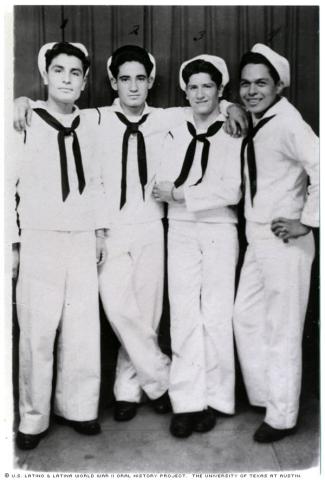

He explained he didn’t want to sign up for the Army because, “I’ve always been sort of a clean person and I couldn’t see myself in the Army dragging myself on the ground.” And the Air Force wouldn’t take him, he said, because “my teeth were in pretty bad shape.” Navy Boot camp in San Diego, Calif., was his first time away from the Los Angeles area.

“I says, ‘What am I doing here?’” Juarez recalled thinking.

Despite being a little freaked out at first, he adapted. Although the training was tough, he says the food was an improvement over what his family could afford back home.

“When I got there we had, you know, different dishes. A lot of the fellas complained about it, but I liked the food. It was good,” said Juarez, recalling they dined on spaghetti and meatballs, Spam and powdered eggs, among other dishes.

After 10 weeks of calisthenics, running, pack-mule-style hiking and other types of training, he was assigned to the U.S.S. Mobile, part of the Fifth Division.

Their first stop was the Hawaiian Islands, where Juarez and the rest of the ship’s crew hand-hoisted sacks of food, ammunition and other supplies onto the Mobile.

“It took all night to load that ship up,” he said.

After a couple of days, they headed for Iwo Jima on a bombardment mission. The Mobile’s duty was to support bigger ships, like aircraft carriers and battleships, as well as to sometimes participate in bombardments. He recalls their job getting pretty hairy at times, because the big ships with which they were working could shoot 19 miles, but didn’t have a field of vision very far beyond that. He and the others on the Mobile couldn’t see the big ships, and vice versa, Juarez said: “They were way out. … Neither one saw each other.”

From Iwo Jima, they went on a bombardment mission to Okinawa, where Juarez recalls arriving on April Fools Day of 1945, not long before land forces got there. Coincidence or not, that’s when the kamakazis started attacking.

Although none ever hit the Mobile, a moving target, the Mobile didn’t have much luck hitting them, either, Juarez says. He describes the Japanese suicide missions through a barrage of chaotic images:

“[S]cary, shooting all those projectiles. … You could see tracers [bullets] going at ‘em, but they weren’t hitting. And you see their plane coming at you, or it’d go right over you … or just fall on the other side. … Juarez said. “Sometimes when you hit ‘em, you figured … it’s just by chance. … [T]hey just keep on coming.”

At one point, part of the crew rescued a kamakazi pilot, took him prisoner and sent him to another ship, something Juarez says he didn’t become aware of until a reunion several years later.

“Usually, when you’re on one side of the ship you don’t know; in battle, you don’t know what’s going on on the other side. And then, you don’t talk too much about it,” explained Juarez, whose job was handling ammunition for the 40-mm 5-inch guns on the sides of the ship.

He says he and other members of the crew would rotate positions. Larger, 6-inch guns were attached to the bow. He recalls that one misfired once, causing a bad explosion that killed everyone in the turret.

Another time, a stopper broke on a gun, causing it to spray bullets uncontrollably.

“It’s scary when you see that gun right next to you, you know, shooting up. It’s not dangerous unless it breaks like that one time. … Two of the fellas got pretty badly burned,” Juarez said.

Next, they headed toward Japan.

“We knew there was going to be a lot of casualties. And then, all of a sudden we heard that the atomic bomb had been dropped [on Hiroshima],” he said.

Juarez recalls hearing munitions experts on the radio trying to figure out how much ammunition it would take to cause such an explosion.

“They said it was hard to imagine how much [ammunition] we would need to cause all that disaster,” Juarez said. “And then right after that, we got the order to head into Nagasaki.”

The Mobile landed there in the wake of the second atomic bomb’s havoc. Juarez recalls staying there about a month.

“We saw the few people who were left there and the damage that it caused. It was pretty much leveled,” he said.

Although Juarez is proud to have fought in the war, he’s critical of the United States for not having taken more after-effect precautions regarding the bomb.

“We never got protection there. We walked right in there … radiation or not, we never knew,” said Juarez, noting that some U.S. soldiers ended up eventually getting Leukemia, a disease he’s tragically familiar with, as his son died of Leukemia as a toddler in 1954.

After Nagasaki, the Mobile was put on “carpet duty,” mainly transporting former prisoners of war out of Japan to other locations. For example, they took a load of previously imprisoned New Zealanders to the Philippines. And they took other former prisoners to Hawaii and the U.S., he says, noting that “old timers” were getting discharged around this time, “so we [the Mobile] had a lot of room for ex-prisoners of war.”

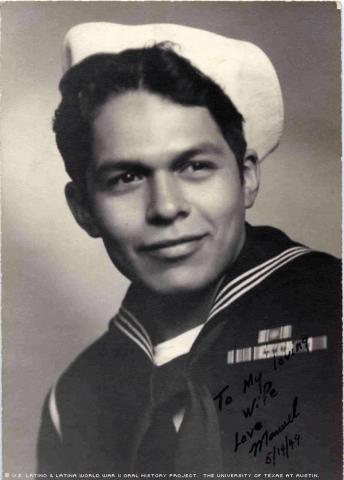

Juarez was discharged August 29, 1946, at the rank of Coxswain. For his service, he earned the Philippine Liberation Medal, as well as other awards.

He said he returned home satisfied, feeling like “we had done what was expected of us.”

Upon his return, Juarez signed up for the reserves. He also got married in Los Angeles on April 8, 1949. He and Rosamaria Fernandez Juarez eventually had five children.

Although Juarez was still in the reserves when the Korean War started, he didn’t go.

“My wife says, ‘Maybe you just better get out of this one. So I got out, got out of the reserve,” Juarez said.

Mr. Juarez was interviewed in Montebello, California, on December 27, 2007, by his son-in law, George Dobosh.