By Chandler Elise Race

As Manuel Castillo stood on the landing barge off of Omaha Beach in Normandy, the battle was already in full motion on shore. For Castillo, the reality of the landing was not the glorified or stirring depictions of the movies: real lives were being lost. Fathers, brothers and uncles were being killed. The memories of those days in 1943 still affect Castillo today.

"They [bombs] explode and let the shrapnel fly all over; you didn't know where to go. A lot of them [the soldiers] would get hit that way," Castillo recounts a memory of a conflict he was involved in.

Normandy was far from Castillo's home in South Austin. His experiences in the Army were very different from the cotton fields, and house painting he had known before he entered the military.

"I, myself, I learned a lot of things that if I would have stayed, had not gone into the service, I don't think I would have learned these other things that I saw," Castillo said in an interview last year.

The Early Days

Times were tough for Castillo's parents and their nine children. Manuel Castillo was the fourth oldest. While the mother stayed home, the father worked very hard as a painter, but still money was scarce. There were times in the winter when the children would have to walk to school barefoot.

The family worked together. Sometimes they helped out the maternal grandfather, who lived in nearby Manor, who had hurt an arm in a car accident and now sold wood.

"We used to go out to the country, this man would let us pick up wood and load the wagon, we loved to be on that wagon," Castillo said.

And every year, the family would travel to Corpus Christi to help pick the cotton crop. After the cotton was gone from Corpus, the family would travel to West Texas to do the same thing.

By the time Castillo returned to Austin every year, it was too late to enroll for the current school year. He would have to wait until the next year.

"That delay in not going back to school in time just set me back," Castillo said. "I spent three years in third grade."

He left school in the fifth grade and began to help his father in the painting trade.

He later worked in many different jobs. Before the war, he worked at Capitol Chevrolet, then as a busboy and as a dishwasher.

The schools that Castillo attended as a child were not segregated. However, the schools he attended were mostly neighborhood schools. He does remember getting along with most of the Anglo children. However, Castillo does remember the occasional taunt about how he and his family should go back to Mexico, or being called "pepper belly", referring to the chili that his family ate. He remembers the children who did give the Mexican-Americans a hard time were the kids from out of town or the "hillbillies."

Life was not all drudgery. The South Austin neighborhood was lively with parties and dances on Saturday nights at neighbors' homes, where mariachi bands would play festive music. It was a time to be with friends and neighbors.

"They would have a dance there almost every Saturday night, and anybody could go there - in fact that is where I learned to dance," Castillo said.

However, the carefree atmosphere of this time disappeared when war broke out. Castillo's first memories of the war came on Dec. 7, 1941, when he heard on the radio that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. This news was the only thing anyone was talking about and it consumed the minds of mothers everywhere, fearing the inevitable.

The War Years

Castillo was drafted into the Army in 1942. He was first stationed at Fort Hood as a truck driver. Later that year, he would be sent to Europe. As is natural, Castillo's parents did not want their son to leave, but he was ready to serve.

When Castillo returned from the service, his brother, Lee, who had been helping their father with the painting business, was drafted.

Through the GI Bill, Castillo went to school to learn skills as an auto mechanic and a welder. However, work was very slow, so he began helping his father with the painting. One job that the two men undertook would change Castillo's profession. Castillo and his father were contracted to do the painting for an apartment complex. The worker that was supposed to do the tile work never showed, so the owner of the complex asked Castillo if he would do it. He told the owner that he did know tile work, but the owner told him how easy it was to learn. From then on Castillo began to work with tile.

Compared to his war days, the days of doing tile work were happy ones. Castillo's experience in the European front of World War II began with his landing on Omaha Beach. "Omaha" was a code name for the second beach from the right of the five landing areas of the Normandy invasion that occurred on D-Day. This part of the Invasion area was under the command of the US 1st Army, headed up by Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley.

The beaches of Normandy were littered with destroyed boats and "Czech hedgehog" obstacles. These were two wooden planks in the shape of an "x", with barbed wire on them to snare soldiers who were trying to move by. There was no room for sitting on the landing barge because it was overloaded. This caused the barge to become stranded for five and a-half hours until a bridge could be built from the barge to the beach.

"We were packed like sardines in there [the landing barge] and we had to wait until the engineers built one of those walking bridge," Castillo recalls. "After they got it all the way there, we got off and we landed and by that time it was already dark. It had been raining. So when we landed in the beach, we were muddy."

After landing on the beach, Castillo and his company were ordered to join with C Company further into the interior. When they found the captain of the company, they were informed that they were not actually joining C Company, but that they were creating C Company. Castillo was expecting to join up with a company, but there was nothing left of the company to join. The company went from France into Belgium.

While in Belgium, Castillo was in the Black Forest for a period of time. In this area, Castillo experienced direct combat with German soldiers, and took part in capturing 29 German prisoners of war. He witnessed the deaths of some friends. During one encounter, a gut reaction told Castillo not to raise himself from his firing position on the ground, as one of the men of his company had just done. The young man who did try to move away was shot down, only inches from where Castillo lay unharmed.

Castillo fought for his country until he was wounded by a piece of shrapnel that pierced his helmet. His life was saved by a corporal from Corpus Christi who dragged him to a slip trench, which is a deep foxhole, and let him stay there for the duration of the battle. Castillo remembers feeling a dead body underneath him in the foxhole.

"He laid me in there [the foxhole] and then I felt something under me and I start touching it," he said. "I don't know if it was a German or GI that was dead, and I was laying right on top of it."

After this skirmish was over, the Allies were ordered to bomb the whole area. It was at this point that the man who rescued Castillo remembered that Castillo was still in the foxhole. He risked his own life a second time to run back to the foxhole and bring Castillo to rejoin the rest of the troops.

"He told me his name but he was in another part of the company; I never got to talk to him," Castillo said. "He took me back and those are some of the things you never forget."

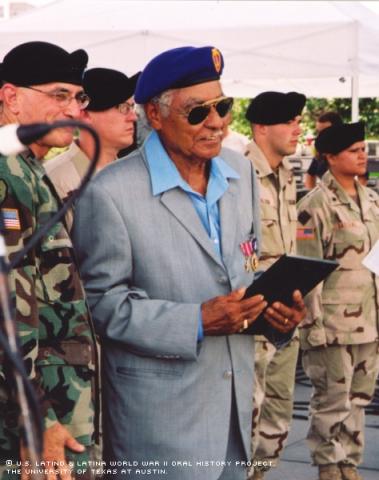

Injured, Castillo was taken to a field hospital, where he was blind for a period of time. He was sent home and taken to hospitals in Staten Island and then in California. The official discharge from the army came in June of 1945. The next two years would be an uphill battle for Castillo's recovery.

After the War

Nightmares and weight loss plagued the young veteran. Not until he began receiving help and treatment form the VA in Waco and later in Austin did Castillo get well. He also attributes his recovery to his second wife, Velia Ledezma, who nursed him back to health. Castillo's first wife was Margaret Ramirez.

Throughout the course of his life, Castillo has run across some racial discrimination. One example happened on a road trip around 1946 in a small West Texas town. Castillo had ordered a cup of coffee to go and was told to wait outside for it. He asked the waitress why he had to wait outside. "Because we don't serve Mexicans here," she said. He refused to take the coffee.

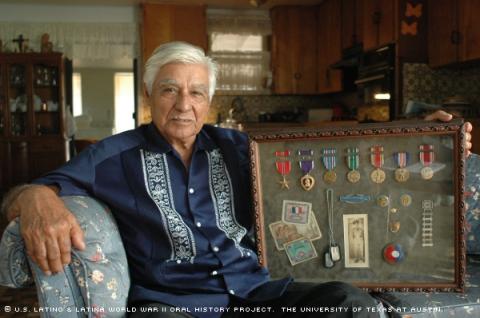

He attributes much of the knowledge that he has attained in life to his experiences in the army, and believes that good advice for all Mexican-Americans is to work hard to better oneself and not to wait for someone to do it for you.