By Haley Dawson

Manuel Lugo boarded a plane in Okinawa, Japan, in November 1969 on the last leg of his journey to Vietnam. From the U.S. mainland to Hawaii and then to Okinawa, the flights had been lively—chattering, joking, laughing. But “from Okinawa to Vietnam, you could have heard a pin drop,” Lugo remembered. “The atmosphere just changed from day to night.”

He was on his way, along with his fellow U.S. Marines, to in the Vietnam War. Nobody on that plane knew what to expect, but they knew it was nothing to joke about. The flight attendants tried to keep up the carefree atmosphere, joking with the men.

“They were trying to make us feel good,” Lugo said. “It didn’t work. We knew, when you got off that damn plane, you’re gonna stay there.”

That’s about all Lugo knew when he arrived in Vietnam.

“You are confused, and you don’t know what’s going on,” Lugo recalled of his battle experience. “You just have to follow orders. … If you don’t, you might get yourself or somebody else hurt.”

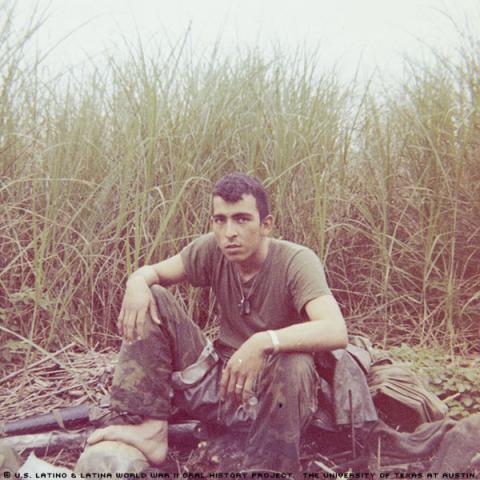

For Lugo, his Vietnam War experience was marked by feelings of being disoriented and lacking control. He was thrown into combat without understanding the final objective of the war. When he returned, there was little effort to transition him from the battlefront to civilian life.

After fighting for his country for 11 months, he returned home with emotional scars that have haunted him throughout his life.

Before he was drafted in 1969, Lugo lived in Phoenix, Ariz., with his parents and his seven brothers and sisters. Family was an important part of his life growing up, and he recalled being happy.

“We were poor, but we didn’t know we were poor,” Lugo said. “We had our food, our clothes, and each other, so it was good.”

His father, Charlie Lugo, a World War II Marine Corps veteran who had been wounded in the Pacific Theater. He was a strict, austere man who worked for the City of Phoenix water department for 37 years and also harvested fruit seasonally in San Jose from 1956 to 1957.

Lugo didn’t understand as a child, but he said he came to believe that his father’s time spent in battle accounted for his stern behavior. He was still an excellent father in Lugo’s eyes, and he instilled strong values in his children, telling them to work hard and to treat others properly. Lugo’s mother, Ramona Mesquita, and father divorced in 1964, but they both maintained a strong presence in their children’s lives.

In school, Lugo excelled at the industrial arts. He had a passion for creating, and his favorite class was shop. He pursued this passion outside of school and apprenticed for his godfather, Frank Torres, restoring old furniture. He eventually made a career as a builder. He built different mobile home parts, such as roofs, for John F. Long, a mobile home builder, for two years until he was drafted in 1969.

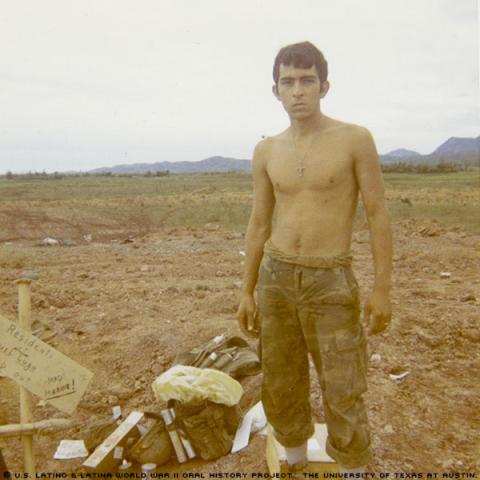

In the Marines, he was trained as a member of a mortar squad. But once he reached Vietnam, he became a rifleman. They needed men on the front line, so regardless of one’s specialty, that’s where he and others went.

From the day Lugo was drafted until the day he stepped off that plane, he said that he felt as if he were caught in a whirlwind of confusion. Boot camp prepared him for war in that sense and that sense alone. He never knew what was going on, but he was always being screamed at.

“That’s exactly how Vietnam feels,” Lugo remembered.

Once his flight arrived in Da Nang, he was immediately taken to the replacement center at the Marine Combat Base at An Hoa to get his rifle, helmet and backpack. From there he was sent to a camp a few miles down the road, where he was based for most of his time in Vietnam. He was never briefed on the situation or told what exactly he’d be doing there. He spent little time at the camp itself; most of the time his squad patrolled surrounding areas for the enemy.

Lugo was in the 2nd Battalion 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division. His unit operated on a three-day schedule rotating between night ambushes, day patrols, and off-days when its members stood guard at the camp. He and his fellow soldiers were never given any information other than being told to obey orders. Sometimes they would move locations, but the schedule was similar. They had no control over where they went or what they did there.

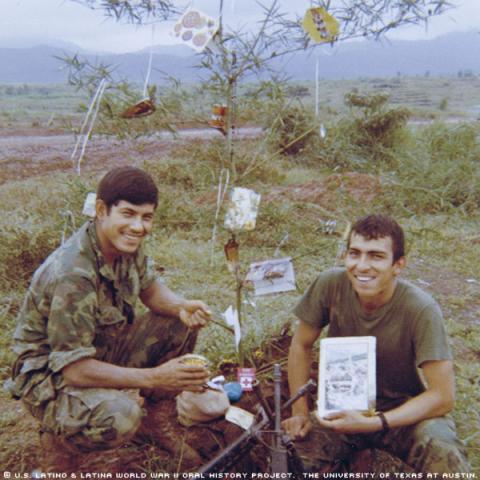

Lugo was promoted to a corporal, and he led a tight-knit squad. Despite the racial struggles occurring at home, it meant little on the battlefront. The black Marines would give one another long, drawn-out handshakes; the Latinos spoke Spanish to one another. The men were all in the same position, facing the same enemy, and they looked out for each other as best they could, he said. In the environment of confusion, they at least had each other to rely on.

“We were there to take care of each other,” Lugo said.

In order to protect his squad members and himself, one objective remained constant: “You are trained for one thing. It’s to defeat the enemy, kill the enemy. And that’s what it was,” Lugo said.

“You’d shoot someone out there [in the fields] and think nothing else,” Lugo recalls.

That idea – how it was so easy for him to adopt that mentality -- made coming home difficult, as did the realization that he had been risking his life daily fighting a war that many people back home did not support. Upon his return, he was berated for fighting in Vietnam. He said people did not want to know about Vietnam.“They look at you like you did something wrong,” Lugo said. “You weren’t supposed to be proud.”

Lugo left Vietnam in 1970 and found himself in a strange place upon his return home. He didn’t know how to deal with what he’d seen and what he’d done in order to survive. Being ripped from combat and thrown back into a civilian environment was a shock, and Lugo was not prepared for it. He was told to just go home and forget, as if “there should be an on-and-off switch,” he said.

But it wasn’t like that for him.

He went hunting with a friend one day and was immediately taken back to the rice paddies.

“I went into ambush mode, I got me a little spot … and I said to myself, ‘If anybody shoots this way I’m gonna kill ‘em,’ ” he remembered. “It’s something that stays in you, that you’re gonna protect yourself. … That switch is never off.”

Lugo was discharged in 1975 with the rank of corporal and was awarded a Navy Commendation Medal with a V device (for valor). It was for directing fire in his direction to prevent another Marine from getting hit, he said. Actions like that, he added, were daily occurrences. Everyone did it because they wanted to see their comrades survive each day. While he was proud to have earned a medal, he felt its significance was trivial.

“Somebody thought I was doing something special,” he said. “To me, it was nothing special. Ribbons are nice, but the stuff you have to go through … they’re not worth it. If you have a friend that you could see once in a while, that’s more worth it.”

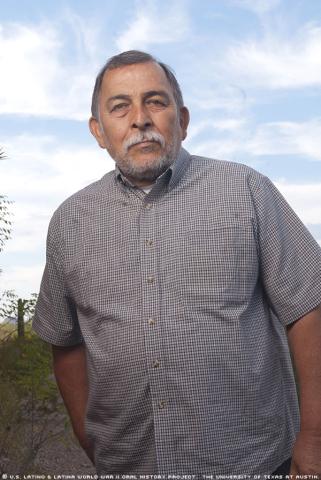

He was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. He received monthly compensation checks, but he felt that the Marines could have done more to help him cope. He was evaluated and diagnosed, he said, but did not receive any treatment until 37 years later.

After returning, Lugo took a month off and then worked at a place that made windows and doors in Phoenix for 10 years. Finally, he quit out of boredom. At the time of his interview he had been self-employed since 1981—with ups and downs in his income, but with total freedom.

“I’ve been happy for 30 years that nobody’s on my ass to tell me ‘You’re late,’ or ‘How come you didn’t finish this?’ or ‘When are you gonna finish it?’/p>

“I get up in the morning, and go do my job because I want to do my job, not because someone is telling me to go do my job, and it’s a good feeling to me,” he said.

Lugo married twice and had been with his second wife, Patsy Mendoza, for 25 years in 2010. He had five children: Aliza, Manny, Irene, Louie and Xavier.

Back in 1969, when that silent flight came to an end, the flight attendants gave the young men kisses as they left the plane and promised to be back in a year to pick them up. Their hopeful words stuck with Lugo, and 11 months later when he boarded an identical plane home, he couldn’t help but marvel that their promise was kept.

The man who flew home was different, however: He was now a man with more questions. Lugo continued to reflect on his time in Vietnam, wondering “Why did we do what we did, and for what reason?” Still, he found his experience to be valuable. He met good people and became a part of their lives.

“I wouldn’t change one day of it,” he said.

(Mr. Lugo was interviewed on Aug., 16, 2010, in Tempe, Ariz., by Michelle Lojewski.)