By David Muto

Martin Sanchez was told after he returned from the war that he’d be welcome anywhere if he wore his military uniform out of the house.

Sanchez laughs while recalling this advice.

“We don’t serve no Mexicans here,” he said in the voice of a shop owner who denied him access to his store, even while Sanchez was dressed in the attire he’d received after enlisting. “You gotta go up by the railroad track up there.”

World War II brought with it a number of changes for Sanchez. Racism, he said, didn’t disappear. And yet – as reflected in his rather stoic attitude toward past hurdles in life – the war presented Sanchez, a barber by trade since 1947, with opportunities for which he now expresses deep gratitude.

Born August 10, 1920, in Beeville, Texas, about 85 miles southeast of San Antonio, Sanchez spent his early years in school, but later found work as a laborer in hard economic times.

“It was tough,” said Sanchez of the Great Depression, during which he; his parents, Martin Sanchez and Rafaela Chapa Sanchez; and two sisters struggled to live comfortably. “There wasn’t work – nothing.”

Sanchez’s luck changed with the inauguration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose New Deal legislation instituted the Civilian Conservation Corps, a public-works relief program that provided manual-labor opportunities and $30 a month for unemployed men.

After his work in the program, Sanchez looked toward the military.

“In the Army, you have everything,” he said, recalling his decision to enlist. “You have rooms, food, a good job.”

After his official enlistment on Sept. 26, 1940, Sanchez was sent to Fort Sam Houston, an Army post in San Antonio, where he joined the 12th Field Artillery. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, however, he was separated from the 12th when the Army moved him to Wisconsin, then Fort Riley in Kansas and, finally, to Fort Bragg, an installation in North Carolina where he was tasked with wire communications.

On July 7, 1945, he was deployed with the 101st Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion to the Philippines, which Japan had targeted in its quest for domination of the South Pacific.

Sanchez saw extreme brutality, he said, some even at the hands of Philippine soldiers, with whom U.S. forces had teamed up to defend the islands.

“They would hold the [captured Japanese soldiers’] heads and cut their necks” with machetes, Sanchez said. Severed heads would be left on the ground.

After the Allied Forces claimed victory, Pvt. Sanchez returned to the United States on Christmas Day of 1945. Officially discharged Jan. 7, 1946, he and his fellow soldiers returned to new lives, and a new nation.

“There was a lot of opportunity,” said Sanchez, noting his barber schooling, which the government funded.

His training helped make it possible for him to eventually open Martin’s Barber Shop, which he has owned and operated since 1962. After the war, he also married Petrissa Alaniz Sanchez, with whom he eventually had three children.

But, despite the relative abundance of post-war opportunity, much hadn’t changed regarding discrimination, he said. For example, when he and three friends visited a bar in Oklahoma one evening, he recalls a waiter denying him service until confirming he wasn’t a Native American.

“There was a lot of discrimination,” said Sanchez, who follows talk of past racism with a lament for the loss of culture he perceives in younger generations of Latinos. While he always spoke Spanish at home as a boy, he and Petrissa’s children, six grandchildren and one great-grandchild are now reluctant to speak Spanish, he said.

“Now the Mexicans aren’t Mexicans,” Sanchez said. “Only the old ones still are.”

Younger generations of Latinos are struggling, said Sanchez, because they “don’t want to learn from their parents.”

“There’s so much ruin,” he said, ultimately adding that his military service taught him discipline in his youth.

“I learned a lot in the service,” he said. “To be thankful.”

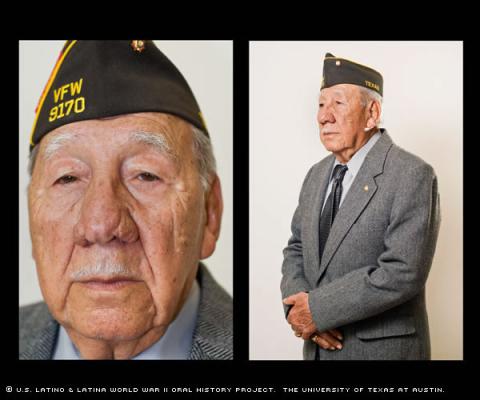

Martin Sanchez was interviewed in Beeville, Texas, on Jan. 10, 2009, by Alcario Alvarado.