By Sonia Nezamzadeh

Miguel Encinias lived what he calls a "child's paradise." Born the youngest of 16 children -- 11 sisters and four brothers -- to Benito Encinias and Manuelia Lopez Encinias, he grew up enjoying photography, music and sports and attended church regularly with his family in New Mexico. In addition to being a student, Encinias delivered the Las Vegas Daily Optic newspaper. His father taught himself English and writing, and worked as a foreman on the second-largest ranch in the nation, in order to provide for his family.

With the arrival of the Great Depression in the early 1930s, the Encinias family lost their Las Vegas home. Miguel, only 16, continued his studies and joined the National Guard between his junior and senior years of high school. He was a sharp talent, one who his classmates perceived as intelligent and resolute.

That intelligence and resolve would serve Encinias well as a pilot and as a prisoner of war during both World War II and the Korean War. Later, after retiring from the military, Encinias would again push himself, this time to earn a Ph.D. in Latin American Spanish Literature from the University of New Mexico.

"I wanted to prove something ... that I was as good as everybody -- being a minority and all that stuff," he said. "I already had a master's degree ... I had gone to Georgetown. I studied in France and got an equivalent of a master's there ... I did my dissertation at the University of Maryland. Again, I was trying to prove something ... to myself and to others that knew me."

After high school, Encinias had thought about applying for Air Force cadet school, which required two years of college (a qualification that was later dropped). But when his friends decided to join the National Guard, he followed their lead.

Encinias was inducted into the New Mexico National Guard at age 16. The Guard was federalized in 1940.

"As war started to form, young Hispanic men in New Mexico started joining the New Mexico National Guard: the 120th Engineer (Combat) Regiment, the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment (Anti-Aircraft) and the anti-tank battalion," Encinias recalled. "The reason for the rush to join was that the battalions were predominantly Hispanic ... from Las Vegas, Albuquerque and Socorro ... almost 100 percent Hispanic."

Young Latino New Mexicans rushed to join the National Guard units because they wanted to serve with others like themselves; many spoke little or no English and would have been uncomfortable in units with few Hispanics.

"The only Anglos in the company were the officers," he said. "But all the enlisted men were Hispanic."

"After Pearl Harbor, there was a great demand for pilots, navigators and bombardiers," Encinias said. He applied for the cadet academy, although it seemed a pipe dream to both him and his friends.

"It was hard to aspire to things like that because being a pilot was considered kind of elite," he said. Encinias surprised everyone when he was accepted.

"All the time I was in training I never met another pilot who was Hispanic," he said. "The washout rate was 50 percent."

Upon graduation, Encinias became a pilot and an officer. He was involved in the "tail end of the Tunisian campaign," and went to Sicily and Corsica. By the time he was shot down over a German airbase in Northern Italy, he had flown 40 missions and shot down three airplanes.

"I wasn't scared of being shot down, I wasn't scared of being a prisoner ... I was scared of being a prisoner in Nazi Germany because I had heard about that area and about the Aryan stuff, and during the Olympics how they had treated Jessie Owens," he said.

Encinias was shot down and spent 15 months in a German prisoner of war camp, near the Polish border on the Baltic Sea. A friend of Encinias’ built a radio from parts he bartered for with the German soldiers.

"We bribed guards with cigarettes ... they were worth their weight in gold." Encinias said. To pass the news of the war to other POWs, hand-printed "newspapers," written on 5-inch by 7-inch notepads given to them by the Red Cross, were passed to one another in the latrine.

"We knew about what was happening ... we knew about the Normandy landing the day it happened," he said. "We could never have believed that Normandy landing could have taken place so quickly.

"One of the things I found out when I was still in the 45th Infantry Division was that we weren't prepared for war at all," he said. "We didn't have uniforms; we had World War I uniforms at first."

He thought back to when the song "I'll Be Home for Christmas" was popular, and how the men half-jokingly hoped to be home by Christmas of 1963. Their plight seemed so hopeless that it seemed it would be 40 more years before they would return home.

But finally, Encinias and the other prisoners could hear the shattering sounds of cannons coming from the east. He recalls opening up ever so carefully the window shutters in hopes the Russian troops would hear their cries: "C'mon Joe!" Their voices cried out for Joseph Stalin's help.

Then one morning, the Germans weren’t there to wake up the prisoners, who ended up shakily walking out of their barracks, afraid of what they would find.

The Germans were gone.

Encinias and three other men used crayons to mark the backs of their uniforms to show they weren’t Germans, as the Russians were killing all the males they found. As the prisoners made their way out of the camp, they came across many dead German soldiers.

At one farmhouse, there were women who’d been subjected to Russian atrocities. They told Encinias and his friends that they had been raped. Nearly 60 years later, Encinias became emotional when describing the encounter with the German women; he said he was sad because of the vulnerability of the women.

"They were so defenseless," he said, still struck by the cruelty of the Russian soldiers.

Back in the States, several weeks later, Encinias bought a copy of "War and Peace" because he had heard some of the other POWs refer to it as the best novel ever written. Then, being a self-described “crazy young kid,” Encinias volunteered to go back to war, this time in the Pacific. The day before being sent to Phoenix, Ariz., for training, word arrived that the atomic bomb had been dropped on Nagasaki; the war was over.

Encinias later served in the Korean War, and got shot down once again.

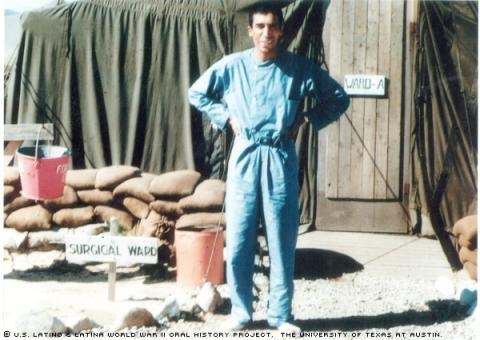

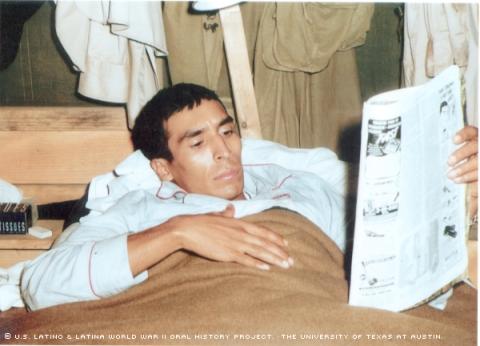

"I was rescued from behind front lines by a helicopter, which took me to a M.A.S.H. unit," he said.

He also helped train pilots from other countries and worked in Spain as a trainer. By the time of his retirement as a lieutenant colonel in 1971, he’d been awarded two Purple Hearts, 14 air medals and three Distinguished Flying Crosses.

Encinias has also worked as a college professor at New Mexico Western University and at the University of Albuquerque, teaching French and Spanish.

In 1963, he married Jeannine Henriette Blondel, a native of France. The two have one son and three daughters.

Former President Bill Clinton appointed Encinias to the World War II Memorial Advisory Board, which planned the national World War II memorial in Washington, D.C.

Mr. Encinias was interviewed in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on December 3, 2001, by Maggie Rivas Rodriguez and Brian Lucero.