By Andy Valdez

The Gil family story is one of overcoming the Great Depression, discrimination and one of service: four of the Gil brothers would answer their country's call to arms.

Paul, Simón, Narciso and Otis would bear arms and defend their country, leaving their home, their mother and their sisters - Ruth, Julia and Sally.

"I think the suffering was here," said Paul Gil, the oldest of the brothers. "I think that's what took my old man. Because he had four boys, we were all married or recently married. And he took that pretty hard. I know because I got to see him when I got back."

In October 1999, Paul, Narciso, Otis and their younger brother, Pete Gil, shared their experiences with the Project.

In 1912, Paul was born to a family of sharecroppers who would grow to raise seven children. For many Mexicans in Gonzales County, Texas at that time, the cotton industry was a lifeline that provided income at the price of intense labor.

At an early age, it was clear that life would not be easy.

"I plowed the cotton. I hoed the cotton. I ginned the cotton," said Paul Gil, of his childhood workload.

At age 7, Paul Gil had taken the place of his father who was fighting in World War I. He was caring for the family farm as well as tending to his sick mother and sister.

Despite hardships, an emphasis on education remained. According to Paul Gil, his mother was able to read and write English and his father was able to read and write Spanish.

A painted white board and charcoal were the learning tools at home.

"She would write the lesson in Spanish and I had to read it to my father in English," Paul Gil explained.

Paul Gil entered a segregated school already knowing how to read and write in both English and Spanish. He even advanced from kindergarten to second grade on his first day of school.

"[The teachers] hated me for being a smart Mexican," Paul Gil said.

The intense discrimination that was plaguing the country was also present in the classrooms at Andrew Chaplin school.

"The cup that we used for drinking water, it was marked 'Mexicans' and the other cup had 'Whites' written on it," Paul Gil remembered.

Early life proved equally tough for the next Gil youth. When asked what he remembered about his childhood, Narciso Gil had a simple answer.

"Nothing but hard," he said. "It was tough in every way."

Otis Gil, recalled traveling with other Mexican workers in the back of a truck to North Texas.

"We couldn't use the bathroom," he said. "We couldn't use nothing."

Otis Gil quit school at age 16 and joined the Civilian Conservation Corps. He was stationed in California and Colorado where he and other men worked building dams and planting shelterbeds on farms. The corps provided employment and training for thousands of young men during the Depression.

While stationed in Colorado, Otis Gil remembered what it was like being one of only a few Mexicans in a large group of Anglos.

"We were afraid because we were always being discriminated [against]," Otis said.

He added that racial tensions ran high in the camp.

"We'd sleep with a knife under our pillow at night. We went to bed with fear and we got up with fear and we thanked the lord that we could get up."

This fearful and challenging childhood was a prelude to a difficult time that none of the brothers could have anticipated.

The United States entered World War II in 1941. Paul Gil was 27 years old and was inducted into the Army at Fort Sill, Okla. Paul kept volunteering for different units in hopes of going overseas.

Paul got his wish and zigzagged across the Atlantic to avoid German submarines.

Three days into the invasion of Normandy, the big steel door of a landing craft opened to let Paul and his fellow soldiers onto the shores of France.

He huddled in a dark barge that was about to reach the shore until the door opened onto the battlefield.

"You're so tired, so disgusted, so everything," he said. "And if anybody ever [says] that he didn't cry, and that he didn't pray, and that he didn't repent, you tell him to come to me. I know because I did all that."

The fear in the depths of the men only doubled once on the battlefield.

"You get so scared until you're not scared anymore," he said. "You're so tired, so sleepy, you'll go to sleep in front of the biggest bombardment."

While doing reconnaissance through a town, an enemy machine gun let loose and Paul was wounded by pieces of a brick wall that shielded him. He was hospitalized for three days before returning to battle through France and Germany.

Paul returned from the war to his wife Lucy Ortiz. They had three children: Paul Jr., Gloria and Joe.

Simón Gil served in the Army in the European Theater, also, leaving behind his wife Elogia Sanchez. He had three children: Theresa, Robert and Rudolf.

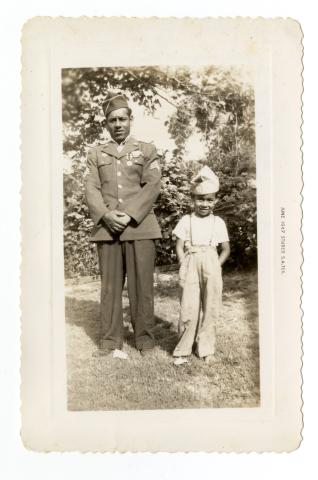

Narciso Gil, who had married Eugenia Aleman, left two young sons, John and Jesse, at home when he boarded a ship bound for the Pacific shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

His ship was not able stop to unload in Hawaii, as everything had been destroyed, he said. As a result, he spent 35 days aboard a ship hopping from island to island in the Philippines looking for a place to land and train.

"We were supposed to get six months of jungle training but we never got them," Narciso recalled.

Eventually, Narciso and his fellow soldiers invaded a beachhead in the Philippines while under fire.

"They were unloading both sides of the boat ... we hit land and started running," he said.

Behind them, the boat that brought them to shore had sunk.

"So we just carried on and we got inland where we could establish ourselves," he said.

He would repeat the drill twice more.

"Every day was the scariest day," he said.

Narciso served as a demolitions expert, disarming mines ahead of the troops with his squadron. Later, he helped in the liberation of labor camps in the Bataan Peninsula.

Otis was the last Gil brother to receive his draft papers. At 19, he left his life in the states to fight a war that had already called upon his brothers. Otis was married to Olivia Rios and had one child on the way.

"Just before I was sent overseas, my first son was born," he recalled. "But they weren't going to let me come and see my son before they sent me overseas."

Otis became an engineer in the Air Corps.

"They do all the dirty work," he explained. "Once they would land, their job was through. Ours was just beginning."

While stationed in San Severo, Italy, he manned a truck that had a machine gun mounted atop it. His troop frequently came under German fire.

"[The] worst feeling is when you look up and see a Swastika airplane on top of your head," he said.

Otis received a medal for shooting down a German plane.

"I had my eyes closed. I don't remember seeing anything," he said. "I was so darn scared that I would be firing and I wasn't ever looking at what I was I was firing at."

Otis Gil also fought a battle in his mind, which at times became another enemy. "Man, I don't think I'm going back," was one of the thoughts he said he could not get out of his head.

"I had one child that I thought I would never get to see," he said. "I got to see nine in the family."

Otis and his wife eventually had nine children: Arturo, Alice, Otis Jr., Amelia, Daniel, David, Richard, Sylvia and Cynthia.

Pete Gil was only 15 years old by the time his older brothers had all left for war.

Too young to join the military himself, Pete recalled the rationing as well as the opportunities that abounded on the homefront.

"All I knew was that they were gone," he said. "They were gone and the families had been left behind. ... but there were some benefits because of jobs opening up, money, inflation. It sort of raised the standard of living."

Soon, Pete's brothers returned. Once home, they tried to put the war behind them and went back to providing for their families, who had struggled without them.

Pete would later marry Frances Rocha and had three children: Vickie, Michael and Elizabeth.

Narciso Gil became active in the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), which he credits with aiding in the advancement of Mexicans. He also joined the G.I. Forum and the Catholic War Veterans.

Narciso and his brothers say they have witnessed a gradual decline in the discrimination that they were subjected to all of their lives.

Landing boats and nerve-eating fear have been replaced with poker playing cards and inside jokes. While the three of them downplay the importance of remembering why they and thousands of others left their families for living nightmares many decades ago, it is evident that deep-rooted emotion is not far beneath the surface.

"Today, you know many times, especially when I'm wearing this [WWII] cap, people come up and say 'Thank you for what you did,'" says Otis Gil, failing to hide the tears that choke him.