By Catherine Mathieson

Contrasts have defined Norberto Gonzalez's life.

Gonzalez appreciates the opportunities the United States has offered him; he came here because he saw none in the tiny Cuban village where he was born.

While serving in the Philippines after World War II, Gonzalez, who grew up poor, watched in pity as Filipinos waited to eat his table scraps.

And even though the United States introduced so many positive experiences into his life, he recognizes the discrimination that confronted him in his adopted country and isn’t shy about pointing it out.

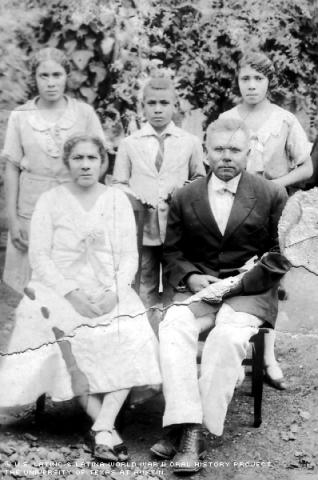

Born Sept. 4, 1919, in the small town of Puerto Padre in eastern Cuba, Gonzalez learned the hardships of life early on.

The youngest of eight children, Gonzalez had to leave school at an early age to help support his family. He worked at a local newspaper but was paid little and worked long hours. In his efforts to learn more, he went to a technical school in Cuba and became a combustion motors technician, knowledge he never was able to use in his native country.

Gonzalez tried hard to learn English because he knew how important it was for his success. So when one of his sister's friends offered an opportunity to go to the U.S., he was quick in accepting it.

Gonzalez arrived in New York City on Aug. 2, 1944. Shortly thereafter, he enlisted in the Army. He remembers learning English during basic training and then being assigned to an all-white battalion. He says he realized he was treated differently.

"They would ask me a lot what my name was and where I was born, and I constantly found myself explaining this to everyone. Once they knew who I was, they would treat me differently," Gonzalez said.

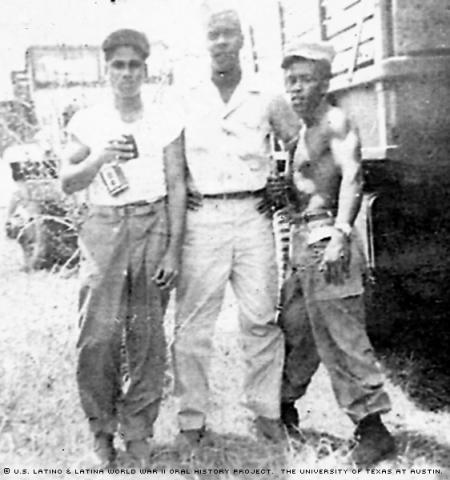

Because of the discrimination he felt, Gonzalez requested a transfer to a segregated, black battalion. It was only then, he says, that he began to feel comfortable.

"My relationship with the soldiers in my battalion was good; they were down-to-earth people. I felt good. I felt like I could progress with them," Gonzalez said.

In 1945 he was sent to the Pacific and stationed in Manila. By then the war was over. Although the Philippines had been librated from the Japanese, Manila had been left in ruins.

"There was a lot of poverty and famine among the population. There was no transport or animals, people had no homes, there was nothing but destruction," Gonzalez said.

Although Gonzalez missed his family, he says life was made easier by being able to speak Spanish with the Filipinos and by the friendship they extended to him.

Gonzalez was part of an engineering force, the 1315 Engineering Construction Battalion, which built new roads and guarded Japanese war prisoners.

He says the Japanese prisoners were treated well because they were cooperative with the American soldiers.

He vividly remembers having lunch every day surrounded by Filipinos hoping to get the soldiers' leftovers.

"That affected me greatly. I thought, how was it possible for us to have so much, when all these people had nothing," Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez, who left the Army as a sergeant, says joining the military gave him a way to help his mother, Juana Gutierrez, and first wife, Lucila Mustelier, who were both in Cuba. The Army would send Juana and Lucila $50 a month, "which at that time was a small fortune. Being able to help them kept me happy," Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez has been married three times and has five children from his last two marriages, all of whom live in the U.S.

In the years after the war, Gonzalez worked as a motor technician. He eventually moved from New York to Pennsylvania, where he lived for many years.

Although Gonzalez wasn’t directly involved in any of the battles in the Pacific, the memories and images of the conflict are still vivid. Many of his war mementos are pasted in a photo album that documents important moments in his history, including his journey back home from the Philippines in November of 1946. Among the awards he received for serving in the Army are the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, the World War II Victory Medal and the Philippine Liberation Ribbon.

Gonzalez now lives a comfortable life in Florida, where one of his sons resides. From time to time, he remembers his years in Cuba with nostalgia.

"My family was very close. We all lived in the same house, and we would take care of each other," Gonzalez said.

At the time of his interview, two of his sisters still lived in Cuba, to where he was planning a trip.

"This country changed my life. By coming here I have grown and made a better life for myself. This country can help many others," said Gonzalez of the U.S.

Mr. Gonzalez was interviewed in Miami, Florida, on September 14, 2002, by Erika Martinez.