By Emiko Fitzgerald

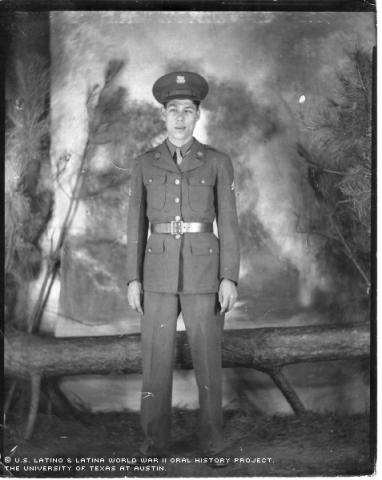

It wasn't until he went for his physical, after being drafted in October of 1942, that Lufkin, Texas, native Norman Gonzales realized he was blind in one eye. However, that didn’t stop Gonzales from serving in the military and, after the war, traveling around the world supporting cleanup operations.

Gonzales had hoped to join the Marine Corps instead of being drafted into the Army. But the physical exam for the Marines revealed he didn’t have vision in his right eye.

"According to relatives, I was taken as a baby to see my grandmother," Gonzales said. "I had a fever and a cold. The wind hit me, and my right eye became crossed."

He hadn’t known about the condition until the exam. But the Army accepted Gonzales, blind eye and all.

Gonzales did his basic training at Camp Robinson in Arkansas, and then became a company clerk for the 766th Military Police Battalion, keeping various records for the company, such as immunization and shooter's documents. His work as the company clerk took him to Louisiana, where prisoners of war from Germany were being held, and to Freeport and Del Rio, Texas. His work involved no combat duties except when President Franklin Roosevelt came to Camp Robinson; then, he "walked a post, on guard duty," he said.

"By and large I enjoyed myself in the Army," Gonzales said. "For me, it was just like any other job."

In March of 1945, Gonzales was assigned to the 1565 Engineer Depot Company, ordering parts for tanks and trucks. As part of his duties, he traveled to the Philippines to deliver supplies to service members who were stationed there. From the hot, balmy weather of the Philippines, Gonzales went to the cold weather of northern Japan, where his company remained for about a month. Gonzales was in the Philippines when the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, and Nagasaki three days later, but he later saw the remains of the two cities while traveling north to Sapporo in December of 1945.

"That place was really devastated," he said. "You could see nothing. The people were really gung-ho about cleaning it up. You could see skeletons of buildings, but everything else was cleaned up."

After returning to the U.S., Gonzales was discharged in February of 1946 at Fort Bliss in Texas, having earned the rank of Technical Sergeant, 4th Class.

He earned several awards, including the Good Conduct award, the Victory Medal, the Philippines Liberation Ribbon and the Asia-Pacific Campaign Medal.

Gonzales went back to his hometown of Lufkin after being discharged, but then moved to Houston, where his family had relocated while he was away.

He was the first American-born child of Refugio and Guadalupe Gonzales, of Higueras, Mexico. The Gonzales family had seven children altogether, the first three in Mexico.

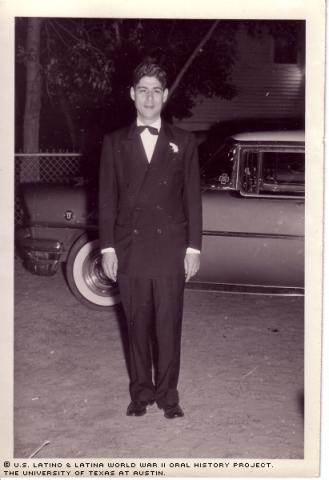

Gonzales grew up and attended school in Lufkin, where he was active with the Future Farmers of America as well as the track team. His event was the mile.

Race was never much of an issue to him, Gonzales said. There weren't many Latinos in Lufkin, and all of his family's neighbors were Caucasian.

"We were treated real good," Gonzales said. "I didn't even think about Anglos, Hispanics, or anything like that until my trip to Henderson, Texas."

On a trip to Henderson with the track team in high school, some of his teammates were concerned about his safety because he’s Latino. They told him to be careful, but the trip was uneventful.

While in high school, Gonzales began working for the Lufkin Daily News as a copy boy. He advanced from sweeping the floors and running errands to setting type as a printer. He continued to work at the Daily News after graduating from Lufkin High School in 1939. At the Daily News, Gonzales learned how to assemble a newspaper, set advertisements and put the paper to bed. Even after being drafted, Gonzales received a three-month deferment because he was "essential" to the business.

After the war, he returned to Lufkin and was offered his former job as a news printer, but he turned it down to move to Houston. It was a difficult transition: Gonzales says he was "disoriented for about a year," unaccustomed to civilian life.

Slowly, he became acclimated. After about a year's time, with the help of the GI Bill, he enrolled in Massey Business College in Houston. With four hours left to earn his accounting degree, Gonzales quit school and began to work full time as a record keeper at Kelly's restaurant, where he was already a part-time employee.

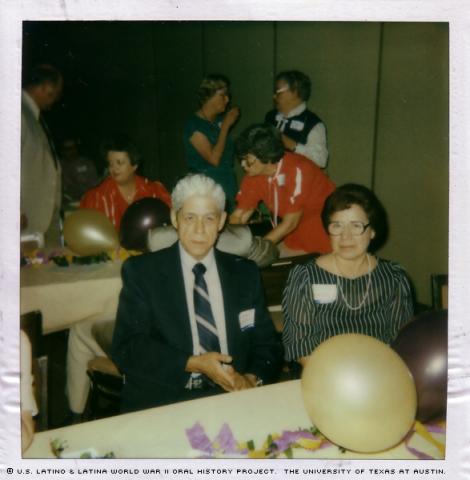

After working in other fields, Gonzales became a postal worker in 1961, working as a distribution clerk and accounting clerk for more than 25 years. His job duties included sorting mail and counting money. He retired from his work as a post officer in 1988.

In 1965, Gonzales married Estefana Hernandez Gonzales, a fellow Lutheran church member. Estefana, who went by the name Esther, worked as a presser in Houston. The couple had no children, and Mrs. Gonzales died in 1999.

Gonzales served as treasurer of his church, Iglesia Luterana San Pedro, for 50 years, until retiring from the position three years ago.

Gonzales says hard work and education are the determining factors for the success of young Hispanics today.

"You can be a governor, you can be a lieutenant, you can be a general now -- you couldn't do that back then," Gonzales said. "But you can't do it just because you're here. You have to know something."

Knowing what he wanted to do -- to serve his country, then take his skills into the Postal Service -- propelled him, Gonzales says, to live the satisfying and fulfilling life he enjoys every day.

Mr. Gonzales was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on February 20, 2003, by Paul R. Zepeda and Ernest Eguia.