By Gabriela Chabolla

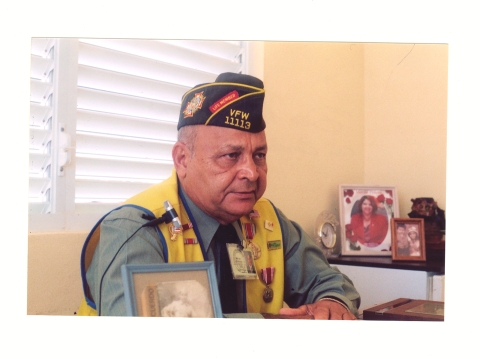

One of 14 children born to parents who worked on a sugar plantation in Guayama, Puerto Rico, Pedro Ramos Santana built his life around hard work and accountability.

His father worked in the field, while his mother tended to the house of a woman named Nena Sabater. Ramos and his nine brothers and four sisters learned the value of hard work at an early age.

“(My parents) told me that a man’s worth is determined by two things,” said Ramos in Spanish, “his integrity and his word. I walked this world with this doctrine.”

From the age of 5, Ramos recalled helping out on the plantation as much as he could, in addition to going to school. One of his jobs was to climb coconut trees and drop coconuts.

“I was a coconut gatherer. Yes, sir, I loved it!” he said. “I’d gather 700 coconuts every day at 15, 16 years old.”

The coconuts were sold to be made into products such as candy.

“In the morning, we had to take a sack with us to feed the pigs. We studied and worked at the same time,” said Ramos, who went to school through the eighth grade. Girls, however, only went up to the fourth grade, as they were expected to get married and not need to work outside of the home.

The ninth child in his family -- he was born May 13, 1927 -- Ramos recalled waking up with his older brothers before sunrise and walking 5 miles through sugarcane fields to get to their 10-student class in the barrio of Puente de Jobos. He recalled the sun setting as they walked back home.

“We were always walking in the dark,” Ramos said.

Even during holidays, Ramos said he and his brothers did not rest. Instead, they made use of their free time carrying water, chasing chickens and oxen, gathering eggs, and making corrals.

Home chores didn’t deter the brothers from excelling in school, however.

“We had the best attendance record and grades,” Ramos said.

World War II didn’t seem to impact the people of Guayama much, Ramos said, because an abundance of plantation crops, as well as local fishermen’s hauls, compensated for a scarcity of items like sugar, rice, salt and flour.

“There were all sorts of fish. ... In August, when there’s plenty of sardines, I’d stick some on a little skewer and fry them,” Ramos said.

He recalled learning about the war through the newspaper El Mundo, then receiving a letter from the Army, asking him to present himself to U.S. military officials.

“I’m not coming back,” Ramos remembered his first reaction being. “You say goodbye forever.”

So he heeded the call to register -- only to be sent back home.

“They turned me down for being a ‘babyface,’” said Ramos with a smile.

“They told me, ‘Go away; when you’re a little older, we’ll call you.’”

Ramos recalled the soldiers asking him to wait four or six months, and, in the meantime, to use a razor on his face to encourage facial hair to grow.

On March 11, 1946, Ramos officially entered the Army, along with his elder brother, Carmelo. At this point, the United Nations had already held its first assembly, replacing the League of Nations. The Allies had won the war; the Potsdam Conference had taken place, sealing Germany’s destiny for the next 40 years.

Ramos’ drafting was a shame, he said, because he was quite the ladies’ man.

“In ’46 I had girlfriends like crazy,” Ramos said with a laugh. “When I graduated [the eighth grade], I’d pay – and it was 10 cents at the movies – for a whole row of seats for my girlfriends.”

Ramos underwent four months of basic training at Camp O’Reilly in the municipality of Gurabo in eastern Puerto Rico. The military taught him to march and cook and assigned him to Company I, 3rd Battalion, 65th Infantry, an all-Puerto Rican group.

Once basic training was over, he flew to Kingston, Jamaica.

“That was the agony of my life. The first time, you always get too scared,” said Ramos, who noted that other passengers had similar reactions.

“They would ask themselves, ‘What if this plane falls? I will no longer live. We will fall and squash the fleas down below,’” he recalled.

More military discipline awaited Ramos in Kingston, as his job for the next couple of months would be to do morning exercises, then spend the rest of the day filling the fuel tanks of airplanes landing in Kingston.

He would get in another round of exercise after that.

“At night, you’d go to the gym to do anything; I’d take a really big sandwich with me,” said Ramos with a smile.

Ramos' next stop was Trinidad, where he recalled suffering from a muscular lesion that caused him to have an accident. One day in 1946, he said he felt dizzy and fell down a flight of stairs as a result.

“The thing is that, in the Army, you have to make an effort even if you can’t,” said Ramos, explaining that his strong sense of duty caused him to push himself too far.

“If I made that effort, it was because I had bosses and I was held accountable to them,” he said.

The extra exertion had a psychological impact as well, he said, noting, “When I left [the Army], I couldn’t sleep.” Falling down a flight of stairs wasn’t the only treachery Ramos faced in Trinidad.

“A Venezuelan woman fell in love with me and gave me a drink that almost killed me,” he said. “It was witchcraft. … She said, ‘If you’re not mine, you’re no one’s.’ And drunk as I was, I took the drink she offered and drank it.”

The woman – who Ramos said he thought was named Victoria – would look for him in the morning at camp and then take him out, he said.

"She’d go visit me at camp, take the captain his bottle and get a pass for me. She’d take me to her house in Port (of) Spain,” he said.

On Jan. 30, 1947, Ramos left the Army. He went back to Puerto Rico to finish high school and moved to New York in 1949.

Then Uncle Sam called once more, this time to serve in the Korean War.

Once again, however, complications delayed his recruitment. The first time he reported to headquarters, Ramos said, he had chicken pox, so the soldiers there turned him away.

Soon afterward, he married Antonia Medina. By the time the Army called him up once more, Antonia was pregnant, so Ramos received leave time until she gave birth.

After the birth of their first child, Ramos said he was again called up, only to be turned down because of complications with some documents. So instead of returning to military life, Ramos went back to school with the financial help of the GI Bill.

“You adapt to other customs and learn more,” said Ramos of his military experience. "(In life), one tries to learn more and more, and see different things.”

Mr. Ramos was interviewed by Humberto Garcia in Ceiba, Puerto Rico, on March 14, 2003.