By Lynda Gonzalez

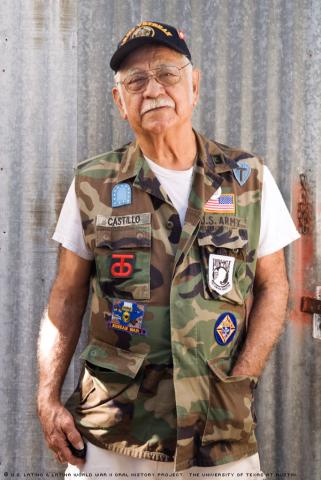

Pedro “Pete” Castillo used his snow-white mustache as a tool in telling his wartime tale, one of the significant chapters of his life.

A sergeant and World War II veteran was in charge of Castillo’s Army company during the Korean War, and he demanded Castillo and his Latino friend shave off their mustaches because, he said, the Army did not like facial hair, Castillo recalled.

“The Anglo sergeant was prejudiced because he never liked for us to speak Spanish,” Castillo said. “We grew our mustaches back when the chaplain said it wasn’t against the law like the sergeant said.”

This made the sergeant angry, Castillo said, and so he never gave Castillo and his friend weekend passes to leave camp. Castillo was a devout Catholic, and his main concern was not being able to celebrate Mass on Sundays. He soon found out from the chaplain that he was permitted by law to attend church. One morning while on guard duty, Castillo left to attend Mass.

“They didn’t bother me after that,” Castillo said.

Born into poverty in Austin, Texas, on Feb. 23, 1931, Castillo was pretty seasoned in the art of surviving adversity by the time he entered the Army.

His parents, Antonio Castillo and Acsención Castillo, met during community baseball games his mother would attend while she lived in Pflugerville, Texas. After marrying, they settled in Austin. For a long time, Castillo lived in what he called “the shack,” a small home with a tin roof that his father built with pieces of wood and scrap metal.

When Castillo’s older brother came home from Army service, their mother rented a small house while their father tried to buy one. Once their father found a one-bedroom house, they had it placed on their property. He later built a porch for the dwelling, where the boys would sleep at night.

As a middle child of seven, Castillo remembered all the family members working hard to provide for each other. His mother often sent them to pick cotton in farm fields as soon as they were old enough, which, in Castillo’s case, was six years old. The money they earned would go toward buying new shoes and clothes for school, and groceries, Castillo said.

Castillo and his siblings would often miss school because the cotton-picking season would cut into the school year. He repeated several semesters at Becker Elementary School, which left him discouraged.

“I didn’t really mind going to school. I really wanted to learn,” Castillo said. “I felt left behind when [everyone] would advance every year and I would always be on the same level.”

He recalled episodes of racial tension in school. For example, certain teachers would not permit him to speak Spanish, or he would face a spanking. He also remembered discrimination during lunch.

“Some of the other guys would take lunch and go someplace and sit down and try to hide, because the lunch they had were tortilla tacos, and the Anglos would make fun of them,” Castillo said.

Once he reached eighth grade, he said he was told he was too old, so he skipped part of the local curriculum to attend Allen Junior High for ninth grade. He continued his education into high school. It was there that a National Guard recruiter approached him.

“A guy asked us if we wanted to join the service, so we went and they signed us up,” Castillo said. “I was 16 years old.”

They lied about their age when they began their weekly training at Camp Mabry in Austin. Castillo continued to attend classes but two years later, while in the 11th grade, he suffered from appendicitis. Once he recovered, he quit school and terminated his service with the Guard. He was 18.

“I’d made corporal running a squad of trucks in the National Guard,” Castillo said. When I got sick, I was up for sergeant. I quit because I had to work to pay off my medical bills. What my dad made wasn’t enough.”

Castillo spent several years working odd jobs to help support his family. Then, on his 21st birthday, he was drafted into the Army. He received the letter while staying with his sister and her husband and working several jobs.

Castillo sat forward in his chair as he remembered a moment during basic training when his ethnicity caused him some trouble. His eyes lit up behind his large eyeglasses as he recounted a confrontation that almost resulted in a physical altercation with an Anglo man. Castillo was in line waiting for a shower at Fort Sill in Oklahoma when he overheard nasty comments about Latinos.

“[The government] had drafted many Mejicanos from the Valley that were there with me,” Castillo said. “They took these guys out of the field; they’d never gone to school. One Anglo made a remark while he was in the front of the [shower] line and said, ‘I don’t know why all these Mexicans are here instead of [in the line for African Americans].’ ”

The man did not know that Castillo spoke and understood English. The man was from the South, and Castillo thought his accent was similar to that of the black soldiers.

Castillo said to a second Anglo man, “I say that he talks like [an African American] so I say he should go back and wait with them.” Castillo said his remark angered the second man, who backed down when Castillo’s Latino friends supported him.

Castillo spent two years in the service, working for the 424th Ordnance Company at Fort Sill from 1951 to 1953. He learned about different types of ammunition and which kinds were most effective in different scenarios.

Though he never went overseas, Castillo said he learned a lot during his time in southwest Oklahoma.

“When you’re in the service, you want to learn,” Castillo said. “I wanted to learn something about whatever is involved. God gave me that knowledge, to be able to learn.”

After Castillo’s father died in November 1952, he did not re-enlist. Missing his father’s death by 30 minutes, Castillo made it home for the funeral, at which point he realized he needed to support his widowed mother.

On March 1, 1953, Castillo transferred to the Army Reserve, in which he said he remained until Dec. 18, 1957. He was discharged as a private first class.

The soft-spoken man clasped his hands over his lap as he recalled his post-service youth. He married Maria de Jesus Herrera in 1953, and they had 11 children together.

He placed high importance on his children’s education.

“We wanted them to better themselves because we knew the world was going to change and the cost of living was going to change, so we wanted them to study,” Castillo said.

In recent years, Castillo stayed active by volunteering in his Catholic community in Austin.

“I was brought up to help anyone who needs help,” Castillo said. “When I do any kind of work, I dedicate it to [God].”

Mr. Castillo was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on Jan. 19, 2010, by Raquel C. Garza.