By Leslie McLain

When Pete A. Gallego returned from World War II after having helped changed the course of history, he found his hometown hadn’t undergone such dramatic transformation. Instead, the population in Alpine, Texas, had stabilized, a stagnant class system remained entrenched and the same urban ills of before were endemic.

Gallego, the son of a Mexican ranch hand, was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1943, when he was 18. The environment in which he grew up discouraged high educational attainment for Latinos. The town of about 3,500 people consisted mainly of ranchers and their workers, the latter typically poor Mexican men with few other job opportunities. Schools for Hispanic children were subpar, segregated institutions across the railroad tracks from the "Anglo schools," he recalled.

Himself a victim of such racial politics, Gallego was unable to begin first grade until he was 10 years old. After illness forced his father to quit his ranching job, the family moved closer to Alpine from the town's rural outskirts to open a restaurant. Once there, it became clear that Latino children were unwanted at the "Anglo" school, so few even attempted entry.

"Alpine was really rough on our people, Gallego said. "The Anglos didn't like the Mexican people except as laborers," he added in correspondence subsequent to his interview. "You couldn't even get a meal at most restaurants, and you could go to the movies if you were willing to sit in the upstairs, separate, 'Assigned to Mexicans' section."

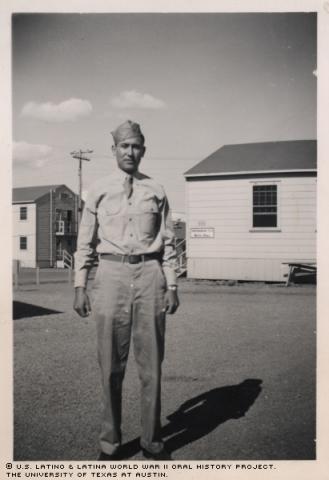

After his induction into the military, he was sent to Salt Lake City, Utah, for basic training, then on to Camp Lee in Virginia for more training. From Camp Lee, he was sent to a replacement Center in Fresno, Calif., where he was assigned to the 1886th Aviation Engineer Battalion at March Field in California. While there, he was notified his father was critically ill, and was given emergency leave to go see him and the rest of his family.

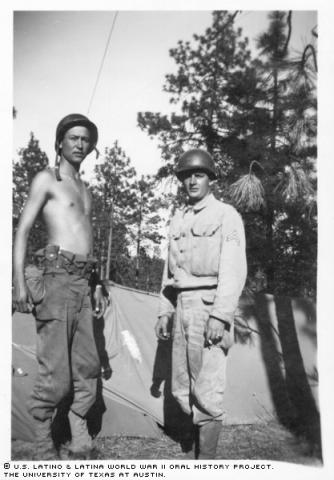

Away from family after his father's death, Gallego took solace in the company of friends in his unit, where bonds transcended cultural differences.

"It seemed weird to begin with, yeah," he said of his new, racially integrated environment. "But after a while, I got used to it. Especially when you're overseas, you have to band together."

When he returned to March Field, he found the 1886th had been shipped to Geiger Field in Spokane, Wash., where Gallego caught up with his outfit, which was later sent to Oahu, Hawaii. It was there he was advised of his father's demise; however, because of the intensity of battle in the Pacific, he was denied emergency furlough to attend the funeral.

The 1886th was transferred from Oahu, Hawaii, to Guam, where they constructed an airfield for the B-29 Super Fortress flying in and out of the island. Here in Guam, the young private suffered a ruptured appendix; surgery was performed at a naval hospital in a Quonset hut near the ocean.

After completion of the airfield in Guam, his outfit sailed in a large troop convoy to Okinawa, where they were to build roads and communications systems and construct fuel tanks and airstrips to help secure the island. They’d been in Okinawa for several weeks before the United States' dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan.

Having attained the rank of Private First Class, Gallego was discharged from the military in March of 1946, having served for two years and eight months. He earned the Victory and the American Theater ribbons, a Good Conduct Medal, and a Bronze Star, among other honors.

Back home, Gallego found that although Alpine hadn’t changed, he had. He’d seen much of the world, and knew his town was far behind in the movement for racial equality. He enrolled at Sul Ross State College in pursuit of a business degree. Three years later, he earned his degree and was one of only four Latinos in a class of 100.

"My career was actually trying to better our people. I was trying to see more [Latino] people get involved in politics and do better than what we had accomplished in the past." He said, adding that education was his "first step" toward that goal.

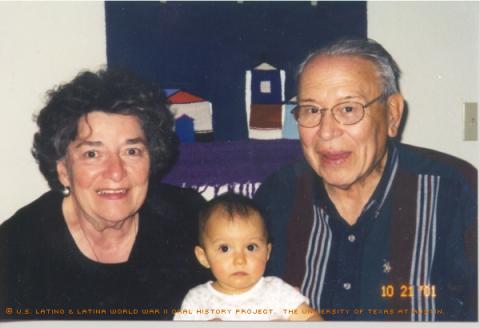

During his first year of college in 1946, Gallego met Elena Peña from Fort Stockton, Texas, and married her the next year. He credits her with being his source of strength throughout his life. Intent on remaining in Alpine, he and Elena took over the operation of his mother's restaurant. They started their own family in 1952, and eventually had four children. Their last child died as an infant in 1963.

Unhappy with the "Latino school" administration, community members asked Gallego to run for a school board seat. He accepted the challenge, but envisioned personal repercussions from those happy with the status quo.

"We knew we were going to suffer in later years for it, which we did, but we wanted to try to get the system equalized for our students," Gallego said.

He was elected as the only Latino to a seven-member board in 1959, and immediately began pushing for school reform and desegregation. Ten years later, an issue arose that galvanized Latinos: The community needed new schools, and bonds were set to be issued to finance construction; Gallego aimed for those schools to be desegregated.

A public meeting was held in Austin, Texas, by the board members, the Mexican Caucus and others intent on access to the planned schools. Gallego knew there was strength in numbers. So with little money or resources, he organized a caravan of 30 to 40 to travel to the state capital and speak on Latinos' behalf.

"The caucus told them it was state law now and they would have to do it [desegregate]. They were very angry that they had to do it," said Gallego, grinning. "They never thought that we would get out there en masse."

Back in Alpine, the harassment began. Gallego and his family received angry phone calls, letters and visits from people unhappy with the changes taking place in their formerly quiet little town. Elena recalled how the local bank manager dropped by their diner to tell her husband he wouldn't have but the shirt on his back if he continued his cause.

"Pete started unbuttoning his shirt then," she said, quietly laughing at the memory. "He said, 'Would you like to have it now?' [The bank manager] got in his car, slammed his door and took off. But after that, we couldn't get any more business. We closed; there was nothing else we could do."

The family was forced to relocate the restaurant across town, near the university. Disaffected by community politics, college students kept the business alive with their patronage.

In 1970, the bond-financed schools were finally built. Even then, Gallego said his forces remained in the fight, checking class rosters to ensure state-mandated integration.

After the segregation battle, Gallego launched other programs geared toward Latinos, including a church credit union and a scholarship fund. After 15 years of service, he retired from the school board in 1974.

The 77-year-old said Alpine, where he lives today, is closer to equality than ever before.

"Never did I strive to be a rich man or to make any money at what I was doing," Gallego said. "It was the principle of getting our people educated to be able to face the world on their own instead of being pulled down by the majority."

Mr. Gallego was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on March 9, 2002, by Maggie Rivas Rodriguez.