By Joanne R. Sánchez

Pete Casarez's fondest childhood memory was playing baseball with his brothers, Frank, Eugene and Frutoso (Tuto) at the Catholic church playground, a half block from their home on East 9th Street in Austin, Texas.

"We were always together," he said of his brothers and himself.

Son of Mexican-born Abraham and Eufemia Casarez, Casarez acknowledges that his family was better off than many during the Depression because his father kept his job at Austin Concrete Company. The family had a 1924 Buick. And his mother "always managed to have food on the table."

During his teenage years, in addition to playing ball, one of Pete Casarez's favorite pastimes was tinkering with the family car. So when he went on to Austin High, then located at 12th and Rio Grande, he enrolled in auto mechanics. Austin High had few Mexican Americans, but he enjoyed it very much and "never had any problems with anybody."

Casarez also worked while in high school, delivering circulars for 15-20 cents an hour. He took a second job as a lens grinder at Globe Optical in the Littlefield Building in downtown Austin.

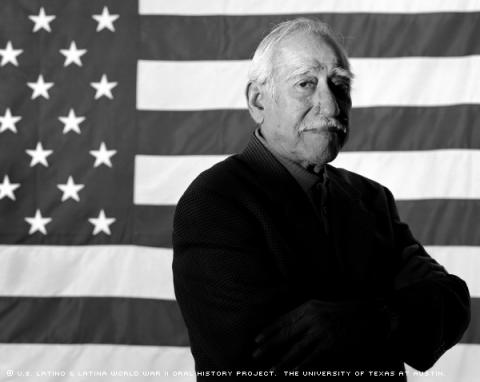

Speaking from his South Austin home where he and his wife, Theresa, have lived for nearly 30 years, Pete Casarez told of his years in the Navy. It was in 1944, after two and half years of high school, when he decided to join the Navy.

"My two brothers [Frank and Eugene] were already gone. I . . . felt like everybody was leaving, so I went ahead and volunteered," he said.

He enlisted with two of his close friends, Alvino Mendoza and Joe Alvarado, and the three of them were in basic training together in Houston at Camp Wallace. At the training camp, there were a few other Mexican Americans from Texas and California.

"We didn't have any problems whatsoever," he said. "[There were] a lot of Yankees and they were really good friends . . . some of them never mingled with Mexican Americans [before]."

From Camp Wallace, Casarez went on to San Diego, and shipped out for Hawaii. The trip to Hawaii took ten days, but the trip on to Guam took another 25 days - at a time when ships were in danger of attack.

"We had destroyers right there with us," he said.

The Navy took advantage of Pete Casarez's knowledge of automobile mechanics.

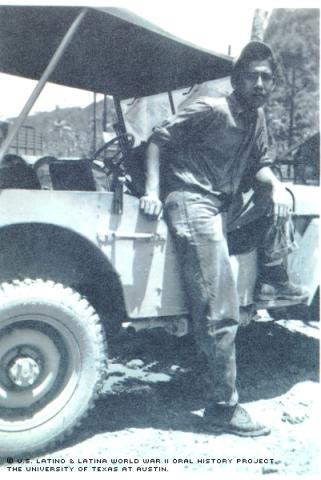

"Studying auto mechanics in high school . . . helped me a lot because it taught me how to handle machinery," he said. "That's why when I went into the Navy . . . they put me in the Seabees . . . the Construction Battalion. . . . And so . . . over there I did . . . greasing the trucks and cars; I drove a truck; I did construction work; I did road work; I did cement work; I did everything."

Assigned to the 25th Naval Construction Battalion attached to the 3rd Marines, he was stationed on Guam for 18 months. The Marines had just taken the island when the Seabees arrived. The Seabees were put to work immediately, building the base.

"They went there and did all of the fighting, and then we [the Seabees] went in ... and did all of the cleaning and building," he said. "We didn't have anything [when we arrived]. . . . We had to build everything. . . . a kitchen. . . . a little church. . . . "The Agana Bridge, named after the capital, was built over a creek by the Seabees in 1945. It remains the main bridge in Guam.

"It was a two-lane and now it's a four-lane bridge," he said, noting that several of his buddies saw it when they returned to Guam a few years ago. "There was still danger because there were . . . a few Japanese left," he said. "At first, we couldn't use any lights at night for safety reasons."

One of the buildings (which still stands) that he helped build was the residence of the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet Admiral Nimitz.

"I helped pour the cement on that," he said. "It was up in one of the mountains. ... When we were working . . . he'd say, 'Hi there. How are you all doing?' He looked like a . . . down to earth person. We built him a nice two-story home with a tennis court. He was there up until the end of the war."

The enlisted men and petty officers slept on cots, four to a tent. "When it rained real hard, we'd get wet," he recalled.

For the first few months, there was little recreation.

"Then we started to get movies," he said. "We had movies every night, the movies that were showing in the United States."

On Sundays, Casarez, who was a truck driver, would borrow a truck so that he and his friends we could take a trip.

"I'd have to have seven or eight signatures first," he said. "We'd go all day . . . . to the other side of Guam to the beaches swimming or to the mountains [and caves]."

To Casarez's surprise, there were many Spanish speakers living in the village across the street from his base. These Spaniards and people of Spanish descent were there because Guam had been a Spanish colony from the mid 1500's until 1898.

"There [were] ships that came in [from Spain] and many [of the people] couldn't go back," he said. "I got to know a lot of them."

Food was very scarce on the island, due to the war.

"The natives hardly had any food," he said. "They used to ask us about sugar, so we gave them some."

Casarez says that he and two cooks who lived in his tent gave the natives leftovers.

In return, the natives gave them liquor made out of palm trees.

"It was . . . delicious," he said.

The monotonous diet of the Seabees is something Pete Casarez does not miss."When we first got there, we were eating nothing but canned food," Casarez said. They had no beer or eggs for over a year.

"Every Wednesday morning, we had beans for breakfast. ... That was a Navy tradition," he said. "One of the things, too, that we used to eat a lot was Spam. I still haven't eaten it again." Like the other Seabees of the 25th Naval Construction Battalion, Casarez stayed on Guam until May 1946. They continued to build roads, bridges and buildings.

Casarez related a surprising event.

"One day we were going to the mess hall to eat . . . and there comes . . . six Japanese soldiers with their hands up," he said. "Our Seabees didn't know what to do except they got their rifles. . . . These . . . Japanese soldiers were hidden in those caves where we used to go and play . . . for over a year. . . . Can you imagine, after a year they came out and wanted to give themselves up? . . . They didn't even know that the war was over."

Back home, with three sons overseas in the war, Eufemia Casarez "was always in church, praying for us."

It was especially difficult for the family because the Casarez boys had never left home; now all three sons were gone. There were two sisters, Mary Louise, and Nelly at home. A fourth brother, Robert, or "Beto" born in 1960, would be adopted later.

"Nobody ever knew where I was. I could write letters, but I couldn't tell them where I was," he said. For Casarez the war was a maturing experience.

"I learned to live by myself," he said. "I traveled to all those places . . . that I had never seen. It opened me up. . . . You learn an awful lot."

He said the war had a profound impact on many Mexican Americans.

"When some people went into the service, they did not have anything," he said. "When they came back, they were offered jobs. . . . Some went back to school or went to trade school. . . .Of course, the military would pay for it. A lot of them took good training, so they had good jobs."

A week after his homecoming in May 1946, Casarez started to work for Doctors Thomas Ward and Wilbur Treadwell, optometrists in downtown Austin. He began as a lens grinder, and later learned how to fit glasses. He worked there until the doctors retired. Then he was hired by Precision Optics and later by Dickenson Optical, where he worked for 25 years - adjusting glasses for thousands of people, including governors and senators.

"I had a lot of good patients. ...They were all very happy with me because I did a good job," he said. "I serviced and fitted glasses for lawyers . . . representatives, . . . governors, the Shivers, . . . and one time I even adjusted glasses for [then Senator] Lyndon Johnson."

Unlike some of his friends who experienced discrimination in Austin in the 1940's, 50's and 60's, Casarez said he had no problems.

"No one ever said that they didn't want me to work on their glasses," he said. "I was able to go all over town and never had a problem."

He attributes the growing acceptance of Mexican Americans to changing attitudes caused by the war.

"People knew that we went into the service to protect them, so there were [many] people who changed in a lot of ways right after the war," he said.

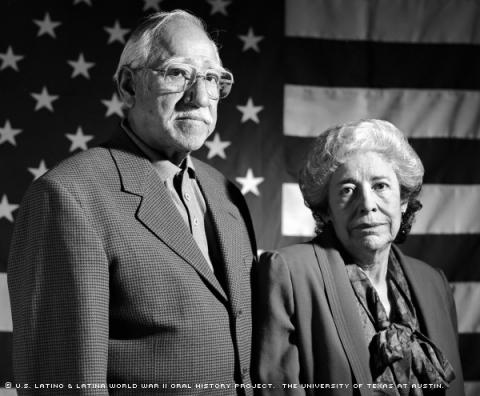

Returning to Austin also meant seeing Theresa Herrera again. Although they corresponded during the war, they did not start dating until1946.

"We went dancing. . . . She was very involved in Zaragosa Park and . . . those type of (Mexican folkloric) dances," he said. "One day we went to a night club and I took an engagement ring."

Pete and Theresa Casarez were married in February, 1948, and they lived with his parents for the first few years. Then, with the help of a loan from Austin Savings and Loan, they built a home on Oltorf Street.

"It was an amazing thing because very few people owned a house in those days," he said.

The couple raised four children: Pete Jr., Carlos, Herlinda, and Veronica. While the children were growing up, Mr. and Mrs. Casarez were regular volunteers at their school, and they were very active in the Parent Teacher's Association.

"We were always right there with them,'' he said. "And they knew it."

Today, Pete Casarez volunteers his time with Post #1805 of the Catholic War Veterans, which he helped to found in 1951. He serves as an usher for San José Catholic Church, and he is also active in the American Legion.

Casarez believes that the school drop-out rate is one of the major problems that Mexican Americans confront.

"A lot of blame is on the parents because they don't push [their children]. A lot of . . . Mexican American parents don't belong to the Parent Teacher's Association," he said. "When you don't belong, you don't know anything about your children."

Pete Casarez's advises the younger generation to get a good education.

"Without [an education] you are never going to get anywhere. ...I recommend that any child be always thinking about school. . . . and not just . . . about pleasures," he said. "You can go to school and still have a lot of fun."