By Erin Dean

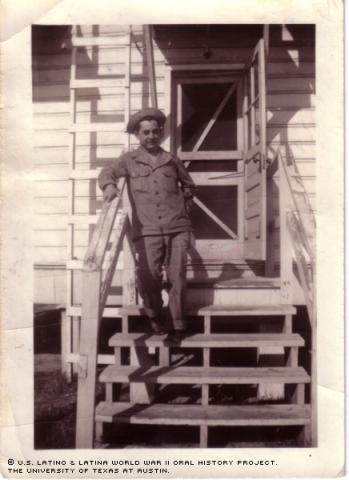

Everything is "beautiful" to Ralph Chavarria, an 88-year-old World War II veteran of the Pacific Theater, who is, to this day, a well-known musician in the Phoenix, Ariz., area.

Chavarria survived a tough childhood full of discrimination and segregation and was drafted at the age of 27, by which point he was already a husband and a father. But he describes nearly everything in his life as beautiful.

"It was very interesting and beautiful, but it's war and it's dangerous, ok," he said about his missions as a firefighter in the Air Force.

He relies on a cane but gestures passionately as he talks, and his speech is punctuated with the youthful expression "man."

Chavarria described the colors of the B-29 bombers he worked with.

"The plane was silver. The nose is red. The tail is red. The ocean's blue," he said. "It's a beautiful picture."

He describes his childhood, despite segregation, as beautiful, too.

"My life in Tempe, it was beautiful in parts, but segregation was very bad," said Chavarria, who recalls the Mexicans having their own grammar school.

He also remembers an incident that happened after he got back from the war, when he and a friend went out to a bar near Tempe and were overcharged for beer.

"As soon as we walked in the door, the crowd was like, 'Look who came in the door,''' he said. "So then we sat down and ordered two beers. Then this fat Anglo man walked over with an apron."

Beer was only 25 cents, but the man charged them a dollar per beer, and they paid anyway. Then Chavarria asked for two more.

"Then the guy comes and said, 'Can't you read in between the lines, man?''' he recalled. "So we got up."

Chavarria is full of stories: tales from his childhood in Tempe, playing the violin in his father's orchestra, running away to Los Angeles to move in with his uncle because of his unjust stepmother, marrying and having four children, training and serving as a firefighter in the war and then retiring and moving back to Arizona.

He began playing violin with his father's orchestra at age 9.

"A boy of 9 years playing in his orchestra," Chavarria said. "Now that's something."

One time, about six members of the orchestra, including Chavarria and his father, Pablo, were hired to play for a friend's daughter's wedding. Once the wedding ended, his father's friend, Don Tomasito, wanted the orchestra to keep playing.

"We played 11 hours, ok," Chavarria said. "The people had already gone, but the old man, Don Tomasito, was plastered, man. He was a chubby fellow. He insisted on my father playing, and my father told him, 'Look, everybody is gone. It's just your wife and your daughter and us musicians.'"

Chavarria says Don Tomasito insisted, and finally went into the bedroom and came out wearing a big Mexican sombrero, gun in hand. He pointed the weapon at Chavarria's father.

"'Pablo, you're gonna play for me and I'm not gonna pay you,'" Chavarria remembers Don Tomasito saying. "He kept the gun pointed at the musicians, and finally he fell asleep. Then my father just came down, took the gun away -- fully loaded, man."

Chavarria says Don Tomasito came to their house the next day, apologized and paid them for all 11 hours - plus a tip.

Music was a big part of Chavarria's life. He played upright bass in the Air Force dance orchestra while he was in the service. It has become a family tradition: his oldest two sons are world-traveling pianists.

"The two oldest, Ernie and Ralphie, are the best piano players around," said Chavarria with an amused smile.

Drafted in February of 1943, Chavarria and his wife, Consuelo Huerta Chavarria, already had Ernie at the time.

"When I was drafted, I was lost, man," he said. "I didn't want to."

Once, when he came home on leave, after being gone for 10 months, young Ernie, then 2 years old, didn't even recognize his father and backed away. This didn't last long, however; after Chavarria returned to his assignment, young Ernie proudly told everyone that his dad was "overseas."

Chavarria was first assigned to a chemical warfare division in the Army, but the assignment was changed, because no chemicals were actually used in WWII: countries threatened to use them, but none actually did so, according to the Organization for Prohibition of Chemical Weapons Web site.

About one year after Chavarria was drafted, he started training in New Orleans to be a firefighter for the Army Air Corps. He then took a 32-day boat ride to Guam, "zigzagging" to avoid submarines. He stayed there for two weeks, he says, before going about 90 miles to the small island of Tinian in the Northern Marianna Islands, where he saw no combat action.

Chavarria was called out when a plane crashed and caught fire. "When there's an emergency, you see the ambulance, you see the fire truck come down," he said. "That was my job."

The United States attacked Hiroshima, Japan, on Aug. 6, 1945, and Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945, and Chavarria was there for the take-off of the planes bearing the atomic bombs.

He says mystery surrounded the mission: Support crews didn't know which planes had the bombs in them, and that scared them.

"It was all scared, man," he said. "Suppose that plane would just crash here. We would just disappear, man, and I sweated."

Chavarria says he and his fellow firefighters felt "pretty bad" about bombing the cities, but that it was just a part of war.

"We never talked about it because we were all hurt from what they did at Pearl Harbor," he said.

Chavarria was discharged in January of 1946. He received the Good Conduct Medal, the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal and the World War II Victory Medal.

After he returned home, he attended the Arizona State Vocational School under the GI Bill.

To this day, he’s something of a celebrity in the Phoenix area for his many years as a musician with the "Chapito" Chavarria Orchestra. He plans on playing violin in this year's Tempe Fiesta, in which three orchestras and two Mariachi bands will perform, a beautiful and fitting return to Chavarria's roots.

Mr. Chavarria was interviewed in Phoenix, Arizona, on January 4, 2003, by George Diaz.