By David Muto

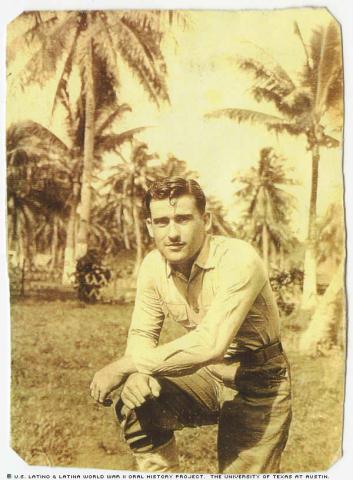

Raul Escobar hesitates while recalling memories of bodies lying on the sands of Iwo Jima. He bows his head before continuing, repositioning a cap reading: “Once a Marine, Always a Marine.”

“I used to get so many flashbacks,” said the 82-year-old Escobar, breaking the silence that lingered after he recounted the story of a fellow Marine dying from a shot to the head.

Various images invade Escobar’s memories of his experiences as a member of the United States Marine Corps from 1943 to 1947 during World War II. In 1945, Escobar traveled with the Third Marine Division to the island of Iwo Jima off the coast of Japan. U.S. forces expected the battle to be brief, hoping to take the island from the Japanese in a matter of days. But the well-fortified enemy “fought like hell,” recalled Escobar, and fighting raged for 35 days, according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

For Escobar, though, the devastation was already a familiar sight. Before setting off for Iwo Jima, his division had landed on Guam, which U.S. Marines were trying to reclaim from the Japanese, who’d captured the island following their attack on Pearl Harbor.

Escobar sailed for Guam at the age of 17, and says his first encounter with the enemy on the island in 1944 was “hell – can’t describe it any better.” Injuries, destruction and death came right away, he says.

Born Oct. 23, 1925, in Ben Bolt, Texas, Escobar was the oldest of eight children. He moved to Corpus Christi at a young age, where in 1942, while working as a dishwasher, he enlisted in the Marines without his mother’s permission. Higher-paying jobs were scarce in the wake of the Great Depression, says Escobar, explaining his decision to join the armed services. Also influencing his decision to join the Marines, an uncle, Jesus Munoz, had recently returned from serving in the Army and spoke unfavorably about the level of toughness required, thus, pushing Escobar to pursue serving in the Marines.

The first in his immediate family to enlist in the armed services, Escobar entered basic training in San Diego, Calif., before fighting as a machine gunner and flame thrower in Guam and Iwo Jima, which the U.S. successfully recaptured in 1944, according to the Army’s Center of Military History.

In Iwo Jima, he received the nickname “Crazy Escobar” for his reckless behavior on the battlefield, which he attributed to a letter he received from his wife, who wrote to tell him she was divorcing him because she didn’t think he would survive the war.

“I didn’t fear danger” after that, he said.

Despite fighting for weeks in Guam, he “didn’t know what the hell to expect” before embarking for Japan, he says.

He remembers being cold and hungry at night on the island of Iwo Jima, and recalled the “awful smells” of enemy soldiers burning to death from his flame thrower.

“The hardest part was seeing some of your friends get killed,” Escobar said.

The battle of Iwo Jima ended March 26, 1945, when U.S. forces claimed victory. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, more than 6,000 members of the U.S. armed forces and more than 20,000 Japanese troops lost their lives.

Escobar is reluctant to discuss the lives he took while fighting on the island. He pauses to regain composure when the subject comes up, then tries to brush it away. What didn’t scare “Crazy Escobar” then does scare him now, he says.

During the war, Escobar’s commanding general presented him with a letter of commendation for exposing his life on the battlefield “above and beyond the call of duty,” wrote Escobar after his interview. But he returned from the war angry and bitter, he says, shaken by his experiences and upset that a Washington politician was calling for isolation and rehabilitation for all Marines because they were “trained killers.”

“We were trained to kill the enemy – not our own,” Escobar said.

He drank heavily after the war, but says he eventually calmed down and became an aircraft electrician in Corpus Christi, Texas.

Today’s young people, he said, must take advantage of their opportunities and “get on the gravy train,” a lesson he learned during his post-war years. Not until he stopped being complacent did he achieve success, which came through buying and selling cattle, he says.

Battles on the shores of Iwo Jima and Guam seem to have left a dark indelible imprint in Escobar’s mind, rendering him unable to expound on certain aspects of life during the war.

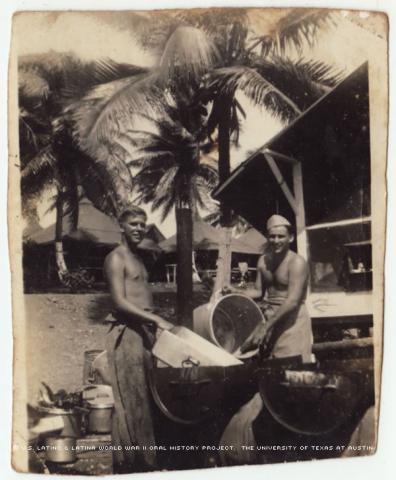

He frequently looks back with fondness on happier experiences, however. For example, he interrupts his discussion of fighting in Guam to recount how he and fellow Marines would make their own alcohol, mixing and storing raisins, apples and apricots and hiding the concoction in the ground to keep it out of sight from officers. They would remove the mixture, called Raising Jack, at night and enjoy each other’s company.

“We had our bad days and our good days,” Escobar said.

Mr. Escobar was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on November 21, 2007, by Raquel C. Garza.