By Erica Sparks

Unlike most World War II soldiers from the U.S., Reynaldo Benavides Rendon joined the military to get out of jail.

He wound up there in 1942 after an immigration officer outside of Corpus Christi, Texas, stepped onto a bus on which Rendon was riding. He’d been picking cotton in Mississippi with his father and was headed back to Robstown to recruit workers to help out on the plantation.

According to Rendon, the immigration officer asked him where he was born so he gave an honest answer:

Mexico.

Then the officer asked Rendon if he had any papers, and Rendon again replied honestly:

He didn’t.

Rendon says he was taken into custody, charged with not having legal papers and incarcerated for eight to 10 days.

While under arrest, he says he made friends with some Jehovah’s Witnesses, who’d been detained because they refused to participate in the war because they didn’t believe in killing fellow human beings. Rendon’s new friends told him he could get his freedom back if he was willing to enlist in the Army.

“[One] asked me if I would ever kill someone. I said I didn’t want to kill anyone, unless I had to out of defense and they were attacking me,” Rendon said.

He says he was pretty sure, however, that being in the military would beat imprisonment. So when he met with some visiting military police, and they asked him if he would be willing to join, he said yes.

Rendon says Uncle Sam sent him and several other enlisted and/or drafted noncitizens to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, to get sworn in as U.S. citizens, but that he refused to be sworn in because he didn’t want to lose his Mexican citizenship. (Mexico has only allowed dual citizenship since 1998.)

“I volunteered to get out of jail,” said Rendon in writing after his interview. “Not to become an American citizen.”

Interestingly, military historian Dr. Richard Brito, a fact checker for the Project, said in an e-mail, “Soldiers were not sworn in as U.S. citizens before serving in the military. Citizenship, at times, came after service.”

Regardless, Rendon’s military papers say he entered the Army in late 1942; one document says Oct. 23, 1942, the other, Dec. 23, 1942, at Fort Sam Houston in Texas.

He says he attended basic training at Camp Robinson in Little Rock, Ark.; then went to a series of other camps. He was receiving engineering training at Camp Elis in Illinois when the war started coming to a close.

“By the time our training was over[,] the first of the atomic bombs were dropped[,] ending the war,” Rendon wrote.

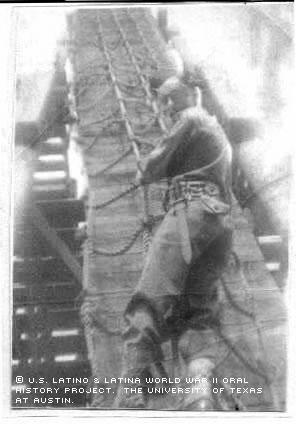

The military still shipped Rendon to Europe, however, where he served as a truck driver with the Army’s Company E, 1309 Engineer Regiment, also known as the Eager Beaver Regiment. According to Rendon’s papers, he “hauled military supplies, equipment, and personnel. Lubricated and serviced vehicle. [And] drove over all types of terrain and through all kinds of weather under combat conditions.”

Interestingly, Rendon was sent to the Philippines at some point after serving in Europe. His discharge records indicate he earned a Philippine Liberation Ribbon and Asiatic Pacific Theater Medal with five bronze stars, and he confirmed over the phone that he was in the Philippines after the atomic bombs were dropped.

Whatever the circumstances were at the end of his service, Rendon was honorably discharged at Texas’ Camp Fannin on Oct. 22, 1945, at the rank of Technician Fifth Grade, having also earned the FAME Campaign Medal and Good Conduct Medal, as well as having been sworn in as a U.S. citizen earlier that year, on May 10, in Paris, France, upon Germany’s surrender.

“I made a lot of friends” said Rendon of his time in the service, noting that one of them convinced him to accept U.S. citizenship.

When he shared a copy of his honorable discharge certificate during his interview, he said, “I’m very proud of these documents because I served my country.”

Born Sept. 8, 1920, in San Vincente, in the northern Mexican state of Nuevo Leon, Rendon went back and forth between his native Mexico and the U.S. as a child. His parents, Valente Benavides Rendon, a farmer, and Regina Benavides Lopez Rendon, a housewife, had 12 children, and they all lived on a ranch outside of Monterrey.

When Rendon was a young boy, the family moved to Rock Spring, near Del Rio, Texas, to live with his mother’s mother. Valente worked on a cattle ranch and Rendon often helped him. He says he didn’t have much time to go to school; helping his family was a higher priority, so he only completed third grade.

“I couldn’t learn. Since I went only when I had the time, I would come to school confused,” he said.

Living on the ranch during the early years of the Depression wasn’t as difficult as one would expect – at least, not at first.

“We weren’t hungry in those days.” Rendon said. “We had fresh milk and butter and biscuits.”

It may not have been easy working the land, but he and his family didn’t want for anything, he says. As the economy deteriorated, however, their situation declined, so Rendon’s father decided to move back to Mexico in 1930.

But the situation was worse in Mexico, Rendon says, so the family eventually moved back illegally to the U.S. The Rendons’ relocation to Mexico had cost them any hope of citizenship.

Once in the States, the family relocated all over the country, looking for work and a place to stay. Rendon had to look over note cards to remember all of the places he and his family traveled in search of sustenance: Texas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, California, Arkansas, Michigan, Missouri and Louisiana.

“We lived the life of migrants,” he said. “It’s a back-breaking job. If you don’t believe me, you should try it.

“In the winter, we had nothing. The floors were so cold, but we couldn’t do anything about it because it cost too much money.”

After the war, Rendon worked briefly with his father on a farm, but then became a self-employed truck driver.

And, on August 7, 1949, he married Maria de la Luz Lozano. The couple had one child, a son named Ricardo, who served in the Vietnam War.

“He suffered a head injury, but it wasn’t very serious,” Rendon said. “I’m very thankful that he left with his health.”

Reynaldo Benavides Rendon was interviewed in Lansing, Michigan, on February 14, 2004, by Juan Marinez.