By Caitlynn Taylor

“It was the worst thing to happen,” Ricardo Garcia said of his time in the 5th Marine Division in Okinawa.

Garcia spent 10 days on the front lines, waiting in the daylight and fighting and surviving bombings at night. It was on his 10th night, May 16, 1945, when the Japanese bombs got too close–an attack that proved fatal for many men.

Garcia’s unit even thought he was dead, lying under the body of a deceased corporal. It took hours for the medic and others in the unit to realize that Garcia was alive, when they noticed him moving his hand, unable to speak.

“All of that seems like it happened yesterday,” said Garcia, attributing the post-traumatic stress disorder from which he suffered to the incident.

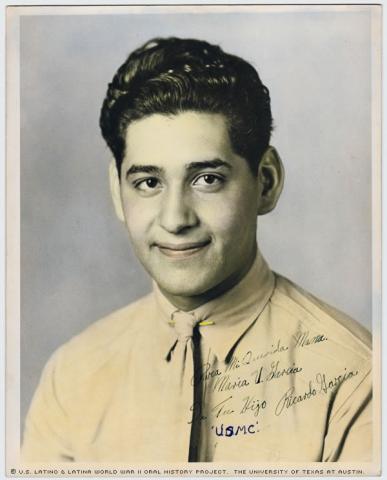

Born and raised in El Paso, Texas, Garcia was one of Pablo and Maria Garcia’s eight children. As a young adult, he moved to San Francisco to work in the shipyards with one of his brothers. Garcia recalled dividing his time between school, work and going dancing. After all, it was the ‘40s, a time when zoot suits reigned supreme and dancing with friends downtown to Big Band music seemed the perfect ending to the week. Garcia recalled living on his wages and sending any money he had left back to his mother.

Although four of his older brothers were enlisted in the Air Force and Navy, Garcia was the first boy in his family not to volunteer for the military. His life as a civilian was interrupted, however, shortly after his 18th birthday, on August 3, 1943.

It was October of 1943; the war was in full force. Garcia received his draft notice while living in San Francisco. He then went home to pick which service branch he preferred, a decision he made based on wanting to try something different from his brothers. He chose to become a Marine. Suddenly, his mother had five sons in the war -- a situation, Garcia said at the time of his interview, about which he still thought.

Boot camp sent him to San Diego, where he recalled the Marine Corps not only strengthening his English, but bringing a heightened realization of cultural stereotypes.

“They thought we were just picked up; but no,” said Garcia, “we had the same things, same education . . . we were just as good as they were.”

Rather than let ignorance get him down, however, he said he refused to allow the language the other Corps members were using get to him. He wasn’t silent, he said, but he did pick his battles carefully. For example, instead of getting upset by trivial comments, he recalled simply giving responses like, “Don’t call me late for supper.”

After boot camp, Garcia was stationed in Hawaii at Pearl Harbor, where he was trained in anti-aircraft machinegun use. The men stationed there became buddies, enjoying the tropical oasis between rigorous training sessions.

Garcia recalled drinking being a favorite pastime. Unlike the Anglo Americans from the Plains, he said his drink of choice wasn’t tequila, but “Te-Kill-Ya.”

Garcia’s unit later took part in the invasion of Iwo Jima. Confronted by nonstop attacks from Japanese soldiers hiding in trees, he recalled being forced to keep a constant, steady eye.

“They didn’t get me. I guess I was lucky. Some of my buddies, they were gone there. I tried to help them, but some of them couldn’t be helped,” said Garcia before growing momentarily silent. “It was alright when you’re doing it, but afterwards, you start remembering; you just can’t get it out of your mind. It’s still there.”

Iwo Jima brought Garcia and his unit face to face with many terrible scenes. He recalled seeing some Japanese soldiers running while on fire, for example. They caught fire from the flamethrowers used to force them out of a building.

Garcia was also involved in the Battle of Iwo Jima, fighting only the equivalent of a block and a half away from Mount Suribachi, as Marine Corps members raised the U.S. flag. He talked about this moment as much more than a photo opportunity. Instead, he said it was a mission; the soldiers were ordered to run to the top of Mount Suribachi. They hadn’t volunteered to do it, and it was a wonder none of them was shot on the way up, Garcia said.

Iwo Jima was worse than his next stint, in Okinawa, Garcia said, even though he was injured in Okinawa on the front lines when shrapnel got stuck in his eye. After two surgeries, doctors gave Garcia two options: lose his left eye or live with a patch. He chose the eye patch, which he still uses.

After three years in the Marines, Pvt. Garcia was honorably discharged on Oct. 10, 1945. For his service, he earned two Purple Heart medals, which, at the time of his interview, he still wore on his Corps hat.

At only 20 years old, Garcia returned to his parents’ home, where his mother took care of him as he healed from his injuries. As he recovered, a romance with a childhood friend named Jessie grew. The two dated before the war, but broke up for some reason Garcia said he can’t remember. During the war, however, she began writing to him, and their romance was reignited.

They were married not long after reuniting in El Paso.

As Garcia was starting his new life with Jessie, he utilized parts of the GI Bill to help him find a trade in a postage shop. But he ended up spending the next 23 years working as a Civil Service mechanic in White Sands, N.M., bearing the 100-mile commute daily by carpool, bus and hitch hiking. He also worked as an upholsterer on the side. Back in those years, Garcia and Jessie raised two boys and two girls, one of whom went into the military.

Today, Garcia is a resident of the Ambrosio Guillen Texas State Veterans Home in El Paso. He said he no longer suffers from the nightmares that used to plague his sleep, but that the memories remain. As a result, he cautioned members of younger generations about getting involved in violent conflicts, advising that they ask what they are fighting for before getting involved. For example, he said he saw no reason to have troops in Afghanistan, Iraq and beyond.

“It was alright when you’re doing it, but afterwards, you start remembering,” Garcia warned. “You just can’t get it out of your mind. It’s still there.”

Mr. Garcia was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on May 9, 2008, by Cheryl Smith Kemp.