By Yvonne Lim

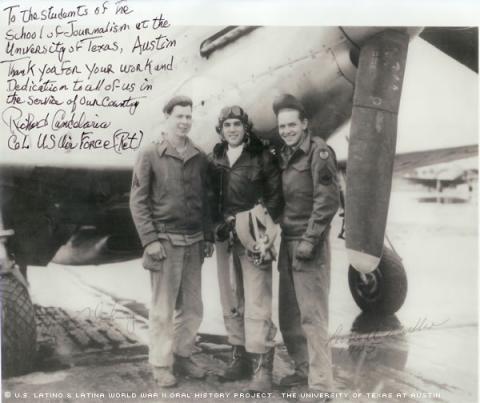

Growing up in Southern California during the 1920s and 1930s, Richard G. Candelaria would bike up to the top of Mulholland Drive to watch the P-38 twin-engine fighter planes take off and land from Burbank. Candelaria read magazine articles about World War I bi-planes, about people like the Red Baron and the Lone Eagle; they inspired him as a boy.

“I wanted to be a fighter pilot,” he said. “That was my one wish.”

Years later, Candelaria lived out his wish when he served as a World War II fighter pilot, destroying German Luftwaffe fighter planes. He shot down six enemy planes, a feat that earned him the distinction of “ace,” and an accomplishment he’s proud of.

“It’s the most exclusive club, or association, in the world,” he said of the American Fighter Aces Association, of which he’s a charter member. “You can’t buy your way in. You can’t influence your way in. You can’t talk your way in. There’s only one way in: aerial combat.”

Candelaria was born July 14, 1922, in El Paso, Texas. When he was only 9 weeks old, he and his mother returned to California.

“My parents wanted me born in Texas,” Candelaria said. “They were on an extended visit to Texas, where both paternal and maternal grandparents lived.”

The only child in his family, Candelaria was 7 years old when his father, an architect, died. His maternal grandmother, two aunts and an uncle then moved to Southern California to live with the family. They lived comfortably for four years, despite the Depression of the 1930s, Candelaria says.

After he graduated from Theodore Roosevelt High School in February of 1939, Candelaria passed preliminary entrance exams for the Air Force flying program. He began studying at the University of Southern California seven months later to meet the two-year college requirement. During this time, he maintained his interest in airplanes by working part time at Miller Dial & Instrument, a company that produced instrument dials for aircraft.

When Pearl Harbor was bombed Dec. 7, 1941, Candelaria says he knew his time to fight for the nation would soon come. After years of waiting, he was accepted into the flying program of the Army Air Force in January of 1943.

Candelaria began his training at the Santa Ana preflight base in Southern California, traveling to several training locations in California and Arizona. In January of 1944, he graduated as a second lieutenant.

“I was selected and assigned to Williams Field and Luke Field, Arizona, as a flight instructor, teaching advanced pilot instrument flying and fighter aircraft gunnery,” Candelaria said.

In May of 1944, when the call came out for fighter pilots, he rushed to the nearest headquarters to register.

“That may sound funny, but this is what you wanted to do, this is what you trained for, this is why you even joined. So therefore, I was happy,” Candelaria said. “I was eager to sign up. I was hoping they would take me – and they did.”

Candelaria’s career as a fighter pilot took off from there. After a series of fighter tactics training programs across the country, he was assigned to the 435th fighter squadron of the 479th fighter group, 8th fighter command, and based at Watersham Royal Air Force Base in Ipswich, England. He was one of only two Latinos in his squadron, and one of only three Hispanics in the entire group – there were three squadrons, or 10,000 to 12,000 men, per group, Candelaria says.

He recalls the camaraderie of the Air Force fondly.

As a fighter pilot, he flew P-38s, twin-engine fighters and P-51 Mustangs, long-range fighter planes. He recalls his mission being to escort and protect bombers to their targets and back.

His greatest personal victory, he says, occurred April 7, 1945, when he shot down four enemy aircraft. That day, because of a slight mechanical problem, Lieutenant Candelaria flew separate from his squadron, and while alone, he encountered two jet fighters and 15 ME-109s, top German fighters. As he radioed his squadron for help, he engaged the lead aircraft of the group. Candelaria recalls shooting the lead aircraft down eventually, along with three others, before his squadron was able to help.

One week later, however, on Friday, April 13, Candelaria’s good fortune reversed when his own plane was shot down over Germany.

“For those of us who are superstitious,” Candelaria said, “it was a good day to stay in bed.”

That morning, he’d flown with his squadron to East Prussia, east of Berlin. Spying enemy aircraft parked on the ground in Rostock, he says he decided to destroy as many as he could. But he broke a cardinal rule: He made a second pass on a ground target, which enabled the anti-aircraft artillery ground troops to zero in on him.

As he flew across the airfield, guns shot up everywhere, along with many cannons – “the famous and feared 88-mm artillery guns” Candelaria said.

He recalls seeing his engine catch fire and steering his plane southwest, toward Allied lines on the other side of the Elbe River. He bailed out of his aircraft.

“The chute opened and I came down,” Candelaria said. “All of a sudden it was so quiet and peaceful. … I almost enjoyed it.”

He was slightly wounded; glass and metal shrapnel had punctured his skin, but his helmet had mostly protected his head.

“I felt pretty lucky,” he said.

As soon as he landed, Candelaria saw a truck of German soldiers firing at something, perhaps him. He recalls running into nearby woods and burying his parachute, waiting until the sun went down to start walking out.

Under cover of dark, with the help of a compass so small he could fit it under his tongue, he made his way southwest, in the direction of the Allies. On his second day, Candelaria encountered two German soldiers in a field of tall grass. He tried to surrender – waving a white scarf – but they fired at him. He recalls firing back, and killing both.

Candelaria then changed directions and headed south. A day and a half later, he came upon a stream he could drink from. He then recalls two civilians, using pitchforks to bale hay, seeing him and charging. He says he shot and killed them.

Candelaria recalls burying his cartridges and changing directions again – this time taking refuge in an abandoned cabin. Local civilians reported him to military authorities, and were even ready to lynch him themselves, Candelaria says; however, the German military got to him first and took him prisoner, during which time he says he was treated well.

One German officer noted he had relatives in Wisconsin, Candelaria says. A German doctor treated his wounds, using Schnapps to sterilize the cuts.

He recalled one driver saying, “You’re a soldier. I’m a soldier. When the war is over, we can go home.”

Candelaria was a prisoner of war for 31 days, until he and a few other POWs decided to escape. They hijacked a German automobile, taking a German captain hostage to reach Allied lines. Candelaria made it safely back to his squadron, and eventually his country and family, getting discharged in June of 1946 at the rank of Colonel.

Candelaria later became a charter member of the American Fighter Aces Association, one of his proudest accomplishments. He also earned many awards, including a Distinguished Flying Cross, Silver Star, French Croix de Guerre with Palm, three Presidential citations and the Purple Heart.

Candelaria married Betty Jean Landreth in 1953, and the couple recently celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. They have two daughters, Camdelyn Marie and Calia Monique.

Candelaria has also had a successful business career, establishing various business enterprises and working in management and administration, all without the benefit of a college degree.

“I never received a degree, a lot of education but no degree,” Candelaria said. “I pulled a, at Microsoft, a Bill Gates thing.”

Candelaria was interviewed in Las Vegas, Nevada, on Feb. 16, 2003, by Mario Barrera.