By Ismael Martinez

Richard Savala and his family worked hard to live the American dream.

Savala's parents moved to the United States from Mexico to provide a better life for their family. And Savala did enjoy a better life: serving his country during World War II to help prepare troops for the Normandy Invasion and bringing home an English bride.

Savala's parents moved to Dallas, Texas, from Guanajuato, Mexico, where Savala’s father, Juan Savala, worked for the Lone Star Cement Company. Savala’s mother, Celedina Chavez Savala, gave birth to him April 1, 1920, in Dallas. While Juan worked, Celedina attended to Savala; his two brothers, John Paul and Gregorio; and two sisters, Florentina and Apolinar. The family resided in one of Dallas' small Mexican communities.

Savala started school at Cemento Chico Elementary, which was dedicated to Spanish-speaking students and was located inside Lone Star Cement Company. One teacher attended to about 50 students of all ages. The elementary provided education for the Mexican community associated with the rock quarry.

"The school was near a forest. The first teacher was mean, but we had good teachers," Savala recalled.

When the institution closed after the Great Depression, Savala continued to study at another school, Cement City Elementary, where he began to learn English.

Savala remembers how he and the other Mexican American children would go home during their lunchtime.

"We didn't want to take lunch to school because they would make fun of us for eating tacos," Savala said.

After learning how to read, he recalls going over the Spanish newspaper, La Prensa, for his father.

But he also wanted to improve his English, so he practiced at home by studying bilingual books. Other children in his neighborhood would tease him when he practiced.

"The other children would call us gringo wannabes," Savala said.

But Savala didn’t get discouraged and later attended Dallas Technical High School, where he continued to learn. He was an honor roll student and enjoyed English and History.

"I got along with the girls because they would always ask to copy my homework," Savala said.

Outside of school, he enjoyed playing sports, listening to Spanish and popular music, watching movies and dancing.

Savala spent plenty of his free time with his family, attending St. Theresa Catholic Church and dancing in Fair Park, among other activities. The dances were progressive for their time because, according to Savala, the Mexican community invited African Americans to join in the festivities. During Christmas time, many Mexican traditions, like posadas, reenactments of St. Joseph and Mary's trip to Bethlehem before the birth of Jesus, were celebrated in the Savala household, he recalls.

After high school, Savala used the local unemployment office to search for a job where he could apply his skills. He found one as a cabinetmaker and worked for about 30 cents an hour for the Watterson Radio Company.

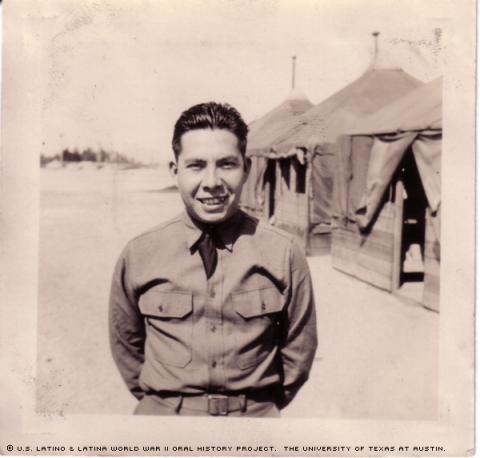

On Nov. 1, 1941, right before the attack on Pearl Harbor, 21-year-old Savala traded his tools for a gun when he was drafted into the Army. After being drafted, he traveled to Camp Roberts in California and McCord Field in Tacoma, Wash., for training until August of 1942. Next, he worked at Drew Field Air Base in Tampa Bay, Fla., for more than a year.

With the war underway, he learned new skills. For example, in Tampa Bay he learned and mastered England’s system of "plotting," the strategy of planning where planes are coming from and where they are going.

After a year, he left Drew Field and taught English soldiers at Swaffan Air Base near Kings Lynn, England, their system of plotting. In his free time, Savala visited London and Manchester and enjoyed the museums, theaters and churches.

During his two years in England, Savala never saw combat, but completed other key duties, including carpentry and handling supplies.

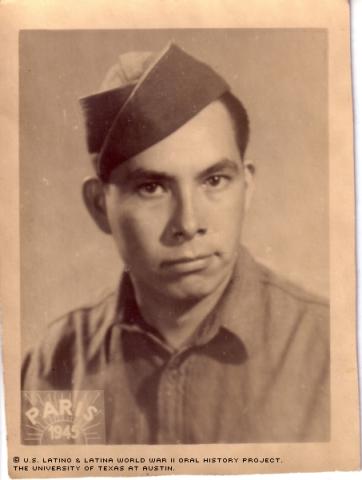

The days surrounding the Normandy Invasion on June 6, 1944, were stressful for Savala and other soldiers preparing for battle. Learning how to use new weapons, like grenades, bazookas and machine guns, also kept them busy. After more training, Savala traveled to France, where he learned the war had finished. He was discharged Nov. 11, 1945, at the rank of Tec 5.

Savala was recognized for his contributions to the war, earning a Good Conduct Medal, European-Middle Eastern-African Campaign Medal, War World II Victory Medal and American Campaign, American Defense Medal.

During his stay in England, Savala met in London his future wife, an Englishwoman named Violet Rosina Land. They only knew each other a month when marrying June 7, 1945, in Wisbech, England, while Savala was on a three-day pass.

Violet didn’t meet him in the U.S., however, until 1947, after the war ended. At first, she wasn’t satisfied with America because of the discrimination they experienced, Savala says. For example, they had a difficult time in Dallas finding an apartment that would rent to them, he says.

"My wife wasn't satisfied with this country. … She thought she was being looked at because she was with me," said Savala, referring to the fact that he’s Mexican and she’s English.

The Savalas’ situation improved, however, when they moved north to Detroit, Mich. Savala started a career with the Great Lakes Steel Company, where he applied what he learned in the Army and surprised his supervisors with his knowledge of gauging. After moving into some suburbs, Violet gave birth to their only son, Robert, who’d eventually graduate from Wayne State University and become an industrial engineer. Savala also helped his grandsons, Robert and Michael Savala, acquire a college education.

"It changed my life for the better," said Savala of education. "I learned more, got along with all and it was easier to find a job."

Savala is now retired and lives in Georgia with Violet. Looking back on his life, he recognizes the many changes Latinos have experienced. For example, he says he sees more Hispanics involved in all aspects of democracy, including politics.

Savala’s advice to other Latinos:

"You have to give a little to get a little."

Mr. Savala was interviewed in Cumming, Georgia, on June 27, 2002, by Anabelle Garay.