By Antonio Gilb

Many of Robert Ramón's wartime memories have faded in the last few decades: Stories of his days in postwar Japan have lost their clarity, and memories of his "nightmare" in the Philippines have dulled in their ability to haunt.

The war, Ramón says, was a couple of lifetimes ago.

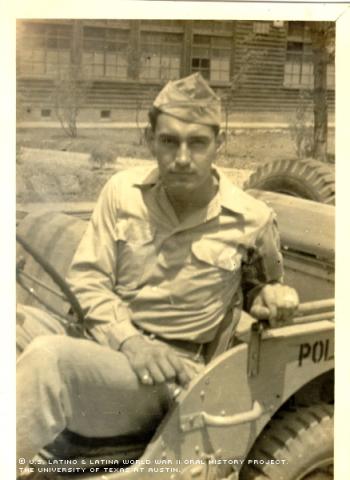

But some memories will never fade. Ramón served with the 8th Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division, having been inducted into service in September of 1944. The regiment's primary mission involved "mop-up" duty in Leyete and Luzon before Japan's surrender. Ramón’s job was to patrol for errant enemy soldiers.

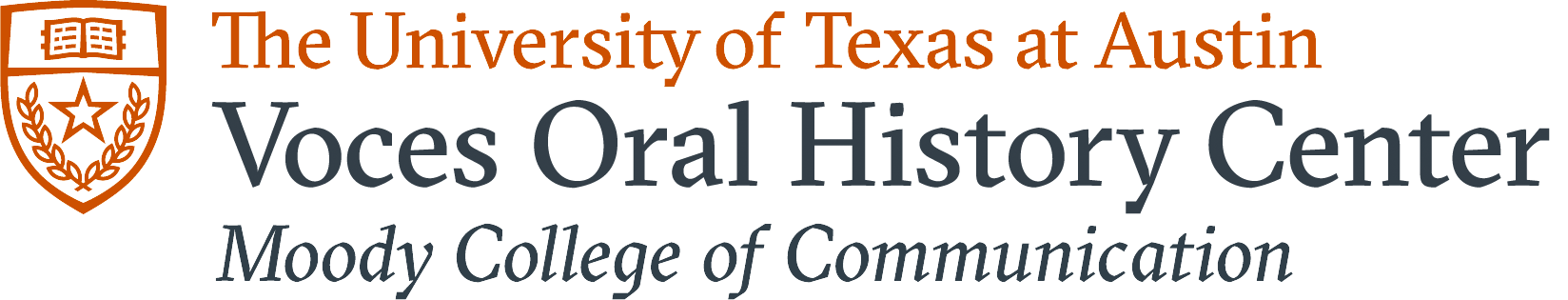

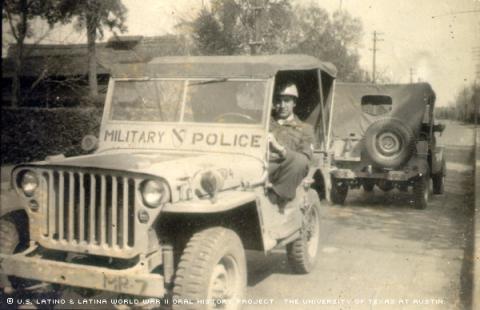

After Japan fell, he was among those landing in occupied Yokohama, Japan, and was one of 40 men selected to guard Gen. Douglas MacArthur in the American embassy in Japan for four months. After that, he was on military police patrol duty for nine months.

Although he served in the war's waning moments, he fought in two battles, killing a Japanese soldier in one and wondering afterward if the dead soldier had a family. He noted he was forced to kill the enemy soldier during an ambush that killed his captain and several American soldiers.

Before serving in the war, Ramón weighed a healthy 190 pounds. Six malnourished months later, his weight dropped to 150 pounds. He subsided on small rations -- cookies he remembers tasting like kerosene, and overly ripe bananas and mangos. Between combat, he battled isolation, torrential rains and thick humidity while under constant threat of Japanese bullets.

But the worst memory -- and perhaps the most vivid -- involves the time his regiment went 72 hours without a drop of water.

"We were so thirsty we were spitting cotton," Ramón said.

Finally, the troop discovered a pond. Their thirst was such, they ignored the protocol taught in basic training of purifying jungle water or shunning it, lest it be infested with harmful bacteria or insects.

At that point, nobody cared.

His nightmare in the Philippines finally came to a close at the war's end in 1945. But lacking the required "points" needed to go home -- based on criteria such as length of duty and number of citations -- Ramón was assigned to be a part of the American occupational forces in Japan.

For the next two years, Ramón patrolled trains and highways as a member of the military police, ensuring Japanese civilians and American soldiers followed the law in postwar Japan.

While on train patrol, he discovered Japanese society held different ideas of chivalry: Men were the first to sit, while women received secondary consideration. Bewildered, Ramón rectified the situation, in accordance to his own culture.

"Get up, let them sit down. Get up," Ramón remembered ordering the male passengers. "We punched them with a stick ... it got to the point where the women were sitting and the men were standing up."

All things considered, life was good for Ramón in post-war Japan; he ate well, easily regaining the 40 pounds he’d lost in the Philippines. He ventured out and familiarized himself with the city's subway system, visiting areas unfrequented by most other GIs and mingling with Tokyo residents.

He even picked up a little of the Japanese language: "The necessary things to get around we learned. 'You're beautiful. Where do you live? May I walk with you? How much?'" Ramón recalled.

While off duty one day, Ramón noticed an attractive young woman riding on a subway train. Wondering whether she was Latina, he devised a plan.

"Que bonita (How pretty)," he murmured to a friend while keeping an eye on the girl to gauge her reaction. The plan worked, and the young lady's eyes lit up.

"Que dice? (What did you say?)" she asked. Indeed, she was a Latina named Laura Ito, the daughter of Mexico's diplomat to Japan. The young lady, also known to Ramón as Laurita, invited the soldier to meet her family.

Ramón says he snapped dozens of photographs during his adventures in Japan. One photo shows him posing in front of Mount Fujiyama, which he tried to climb before succumbing to the thin air at such a high altitude. Another picture shows him behind the wheel of a truck before a night on the town. And, of course, many photographs were taken of Laurita, the beautiful diplomat's daughter who caught his fancy.

But his postwar adventure ended in February of 1947 when he was discharged after amassing the necessary points. Once home, a friend attempted to recruit civilian Ramón into the police force, but he resisted: "By that time, I didn't want to carry a .45 no more. I told him, no, no, I'd take my chances with a truck.'"

Ramón instead joined the Teamsters union and secured a job driving an 18-wheeler rig. Shortly after, he met Concepción Ramirez in Bonita Garden's dance hall in Houston, the woman who’d become his wife.

The two wed on Feb. 4, 1948, after a brief four-month courtship. They also collaborated musically; from 1961 to 1973, they performed in their own band, the Ramón Marimba Combo, with her playing the marimba and him the guitar.

They had two daughters and two sons together, losing one son in the following years in an automobile accident.

Their surviving son, Robert, would follow in his father's footsteps and serve in the Armed Forces – specifically, in the Air Force as a sergeant. He now works for Harris County as the assistant supervisor at the Information Technology Center.

Growing up in the 1920s, Ramón remembers seeing ubiquitous signs on storefront windows reading: "No Mexicans allowed." Now living in Houston, he notes with pride how one of his daughters is an accountant while the other works at a law firm. He partially attributes the sweeping social change after World War II to enhanced opportunities for Hispanics, including his own children.

The Ramóns have spent their retirement maintaining their yard and traveling, recently visiting Washington, D.C.

Mr. Ramón was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on March 2, 2002, by Antonio Gilb.