By Jordyn Davenport

Although Rodolfo Hernandez never saw the frontline of battle, World War II was an exciting time for him.

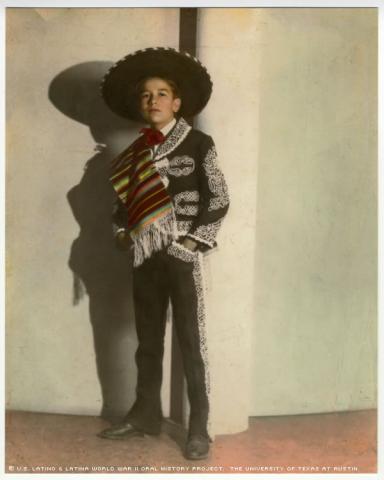

That’s because Hernandez performed with his family’s informal entertainment troupe as a singer nicknamed Charro Azul, for the blue suit he wore on stage.

Born in San Antonio, Texas, on June 21, 1929, Hernandez never had a choice about performing. His father, Francisco Hernandez, grew up as a trampoline artist and later became a dancer and a clown called Paco. And his grandfather, Marcos Hernandez, was a circus ringmaster in Mexico, while Marcos’ wife performed as a contralto singer. Francisco Hernandez trained Rodolfo Hernandez and his six younger siblings to be entertainers. They could all dance, sing and act by the age of eight or nine, at the oldest, Hernandez wrote after his interview.

Hernandez was always comfortable singing, but said speaking before a crowd plagues him to this day. He would frequently have to make a bit of small talk between songs, which made him nervous.

“When I didn’t know how to say something, I would just sing it,” he said.

Beyond the family’s entertainment tradition, Hernandez grew up fortunate, because his father always maintained a steady job, which was a rarity at that time. Hernandez recalled his dad being proud of his position as a supervisor at The City Fish Market in San Antonio.

Francisco also took pride in being a community air-raid warden during the war. He took a class about safety tactics at a local elementary school before becoming a warden, and Hernandez said his father taught him all about first aid and safety.

Other members of Hernandez’s family were involved in the war effort as well. Hernandez recalled his mother, Clara Esquivel Hernandez, supporting Francisco in his duties by, among other things, preparing food for area warden meetings.

And Hernandez said he and his siblings collected aluminum, mostly in the form of pots and pans, for scrap drives. A local cinema, The Majestic Theater, served as a designated drop off site for the scrap and offered a free movie ticket for every donation.

In 1946, the Hernandez family moved from San Antonio to Aransas Pass, Texas, because Francisco got a job at a shrimpery. The family continued entertaining though, and the elder Hernandez organized variety shows for various churches and Mexican organizations.

Hernandez recalled that his father taught many of the local youths how to dance, so they could perform in the family’s shows. The audience members were generally impressed with the dancers. But Hernandez remembered one day when an Anglo spectator remarked, “Well, there’s nothing to that; all Mexicans know how to dance.”

Hernandez said his father responded by teaching a group of non-Latino, white adolescents to dance and inviting them to perform at a local festival.

During this time, Hernandez frequently traveled across the state with his dad to entertain. Among other shows, he performed for WWII troops at Dodd Air Field in San Antonio.

While entertaining the military, Hernandez’s group typically sang the “Star Spangled Banner” before getting into contemporary songs popular with the troops. Many of those tunes were written in Spanish, Hernandez said, but they also sang Spanish versions of popular songs written in English.

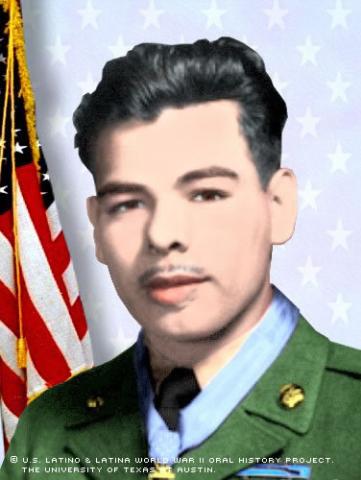

After the war, Hernandez continued to perform as a singer until he voluntarily enlisted in the Army in 1948. He said he wasn’t fond of living in Aransas Pass and figured the Army was a ticket to somewhere else.

He had no idea exactly how far he would travel, or how long he’d end up in Uncle Sam’s employment:

Hernandez’s next four years in the 4th Infantry

Regiment in Alaska turned out to be the beginning of an approximate 36-year career with the federal government, lasting until 1985, when he retired from a long-held supply and quality control Civil Service position with the Air Force.

During his Army days, Hernandez was stationed in both Fairbanks and Anchorage as a ski trooper.

Many of his fellow soldiers were also from the South, he said, and a bit out of their element in Alaska.

“We didn’t know what snow was and they sent us all over there,” Hernandez said.

As a ski trooper, he learned extreme winter survival, including how to fight with skis and snowshoes on all kinds of winter terrain.

Unfortunately, Hernandez lost his ability to sing with clarity during his stay in Alaska. He said the cold air caused sinus problems that gave him a semi-permanent “frog in [his] throat.”

He can still sing, but doesn’t have the vocal stamina to complete a song.

“I’d be ashamed to get in front of an audience and try to sing a song,” he said.

At the time of his interview, Hernandez lived with his wife, Merehilda Hernandez. He met Merehilda after his four years in Alaska, so she never heard his voice before his vocal problems. She said jokingly that he has told her he used to sing, and other people have told her he used to sing really well, so she guesses she believes him.

Mr. Hernandez was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on Oct. 6, 2009, by Peter C. Haney.