By Katy Lutz

Rabbit's Lounge was a dimly-lit, tiny bar that boycotted Budweiser while serving up some of the coldest beer in Austin, Texas. It might have seemed a very unlikely candidate for the Austin hub of Chicano politics in the early 1970s - if one hadn't also met its indefatigable owner, Rosalio "Rabbit" Duran.

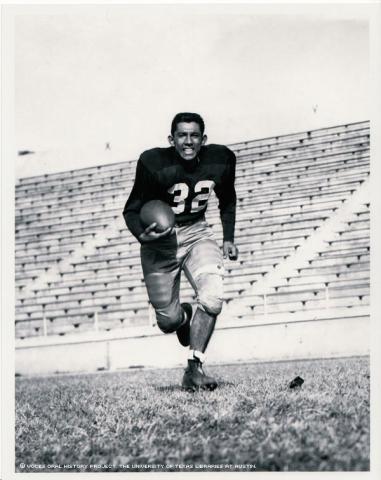

Duran was born to diehard Democrats, Ezequiel Duran and Eva Gonzalez Duran, on May 18, 1933, in Austin. As an adolescent, Duran gained his nickname "Rabbit" because of his incomparable running speed in youth sports.

"I could outrun anybody in [my] neighborhood," he said, referring to youngsters his age, and even two years older. "I was probably one of the 10 fastest persons," he said. "That's how I got my name."

As a child of the Great Depression, Duran remembers his family's willingness to help others who were struggling.

"My dad, and grandma, and everybody used to give everybody food," Duran said, "and they would bring eggs, vegetables and chickens, what have you, in return for the food that my folks had given them."

While he was growing up, Duran's family was considered to be well-off. They owned their own grocery store and service station, Duran's Grocery, on East 7th Street, which Duran's grandfather had bought in 1901. The store sold "groceries of all kind" including wood, kerosene, potatoes, rice and meat from its own butcher.

Duran's parents both strongly identified as Democrats in the early 1940s, under the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Duran recalled that his grandparents, uncles and parents would sit around and talk about all of the political candidates in the 1940s and 1950s in Austin.

"We've always been in politics," Duran said of his family. He said his family members would often say: "We elected all these officials to help us, and all they do is raise our taxes and make us pay more insurance. How in the world are they helping us?"

When he was 17 years old, his mother died of natural causes. She was 41. During his teen years, she had been the one who pushed her children to pursue an education. Duran graduated from Austin High School in 1952.

Duran joined the U.S. Navy when he was 19 and served in the Korean War. He worked in supplies on the USS Oriskany (CVA-34), an aircraft carrier, which made its only Korean War combat cruise from September 1952 to May 1953, almost to the end of official hostilities.

Right after his military discharge, Duran began working fulltime at his family's service station, changing tires for customers.

"I could fix a tire in no time," Duran said.

As the 1950s faded into the 1960s, Duran began to notice a surge in Mexican Americans intent on achieving social and political equality. This was the first time Duran became aware of the segregation that he had endured in school.

"I never thought about [segregation] -- why it was segregated," he said. "It was just a Black thing and a Brown thing... We didn't know any better... We didn't realize [segregation] was happening 'til years later, 'til movements started coming in."

As the 1960s began, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement that he founded inspired many Latinos to activism, in demanding equal opportunities in the Puerto Rican communities in New York and Chicago, to minimum wages and equitable labor laws for farm workers and school desegregation for Mexican-Americans in the West and Southwest. The unpopular military draft and growing national opposition to the Vietnam War helped to power the Latino civil rights activism. For many young Mexican-Americans, it became the Chicano Rights Movement.

Duran recalled that he began engaging with Chicano politics with his friends in 1967 at Cisco's Bakery, "a big political place," in Austin.

But, also in 1967, Rudy Cisneros, the owner of Cisco's Bakery, decided to lease his bakery. Upon hearing the news, Duran boldly decided to rent the space.

And, just like that, Rabbit's Lounge was born.

Duran said his bar quickly gained a strong following within Austin. In need of more space and parking for his customers, Duran paid $14,000 for a new locale and moved his business to a larger building at 6th and Chicon in East Austin in 1969. Initially, it consisted of one room and one bathroom. (Duran would later add an extra bathroom.)

For him, it was a momentous year. Duran married Mary Rousos on April 1, 1969. They had five children: Ryan, George, Lisa, Angela and Catherine.

The welcoming atmosphere and his diverse clientele, he said, made Rabbit's Lounge flourish.

"Everyone was welcome and everyone was treated right," said Duran.

Rabbit's Lounge opened Monday through Saturday at 8 a.m. ready to serve the growing Austin community, and it opened at noon on Sundays. It would fill up early with construction workers who would stay until the afternoon - especially when bad weather prevented their working. Then, at 5 p.m., a new batch of customers, primarily state workers, would filter in for 50-cent "ice cold beer" and to listen to the popular "conjunto" music, small combos that include an accordion, sounding from the jukebox.

Some of Rabbit's best customers were the softball crowd, a mixture of Mexican American working class players and professionals interested in politics. Those softball players became volunteers for any political task that needed to be done, he recalled.

"Some of them drew signs..." Duran said, "We had people who could talk good and go into the neighborhoods and talk about voting."

The sport proved to be central in the 1974 campaign of Bob Perkins. Perkins' run for Justice of the Peace was the first to fully utilize Duran's resources as a political headquarters.

Perkins, a recent law school graduate -- and a popular announcer of local softball games -- used the upstairs of Rabbit's Lounge as his campaign headquarters. It was equipped with a desk, a phone. and it was a place for candidates to get in touch with the Austin community. To inaugurate Perkins' campaign, Duran personally went around collecting contributions.

As Duran remembers, in the beginning, Rabbit's Lounge was a place where politicians would "ask for help, bring their friends, bring their supporters" and promote their campaigns. But soon, he added, Rabbit's Lounge also became a Mecca for up-and-coming Chicano politicians. Whether painting signs, making phone calls or requesting donations, political candidates and their supporters came to Rabbit's Lounge seeking supporters and Duran's help.

"We had a lot of good people... that came to help at all times," Duran said of the volunteers.

Beyond city politics, Duran worked to serve the local Austin community and customers who frequented his bar. For 10 years, Rabbit's Lounge boycotted Budweiser beer, Duran said, "because they wouldn't help the community or support any of the softball, baseball or Little League in the community." While other bars refused to boycott Budweiser for fear of low sales, Duran risked the loss of income and took a stand for his community.

Duran considered one of his greatest achievements the frequent fundraisers Rabbit's Lounge hosted for Austin's needy.

The barkeeper recalled that one man needed a glass eye.

"We helped him get an eye," Duran said. "[Another] didn't have no arms; we helped him get arms... People that needed wheelchairs; we helped them get wheelchairs."

Most of Duran's fundraisers included fish fries and barbecues, where Austin locals contributed both the food and their service. Word-of-mouth and signs displayed on street corners promoted Duran's fundraisers - and he said that turnouts were high.

Whether customers were enjoying a cold beer, debating Chicano politics or helping their fellow community members, Rabbit's Lounge was the place to go.

By 2000, Rabbit's Lounge had proudly helped to elect political officeholders, such as Justice of the Peace Bob Perkins; Travis County Commissioner Richard Moya; Austin City Councilman John Trevino, and several other officials.

For his role in supporting Mexican-American politics, Duran was honored by the Texas Legislature. The bill sponsored by Eddie Rodriguez, commended Duran for his service to the "political and cultural legacy of East Austin."

Rabbit's Lounge's central place in East Austin was recognized in another very visible way as well: with the painting of a mural of farmworker leader Cesar Chavez on an exterior wall of building in 2011. But, while Rabbit's was undergoing that cosmetic upgrade, Duran, at nearly 77 years old, started thinking that maybe it was time to let go.

In the summer of 2011, after 40 years of running Rabbit's Lounge, Duran decided to lease his space. The new tenant remodeled the simple bar and renamed it Whisler's.

Nowadays, Duran spends his time with friends and family, occasionally gambling, or walking around the mall. At night, though, Rabbit comes out to play.

"I'm still a night person. I go to the East Side every night," Duran said proudly.

In the garage of his Central Austin home, Duran keeps the old jukebox. which he sometimes gets to play one of his favorite songs, "La Charanga."

"You can shake and shake as much as you want to that song," Duran joked, reflecting on memories of his bar days.

While Duran has already impacted Austin by helping to launch political careers, he still hopes to leave his mark on the city.

"There's a short street near my old neighborhood that I think I'd like them to have my last name put on... Duran Street," he said.

With a lifetime of accomplishments set in the Texas capital, Rosalio "Rabbit" Duran also knows the name by which his community will remember him: "Rabbit... I'm gonna have it put on my ...tombstone."

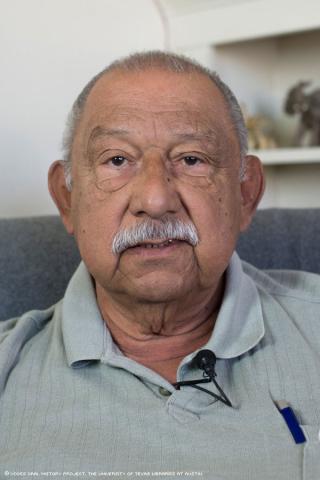

Mr. Duran was interviewed by Katy Lutz in Austin, Texas, on March 17, 2014.